Virginia B. Hart is the fifth director and curator of the US State Department’s Diplomatic Reception Rooms, having previously served there as assistant curator. Since starting work in 2008, she has established the Rooms as a robust and publicly accessible museum collection.

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

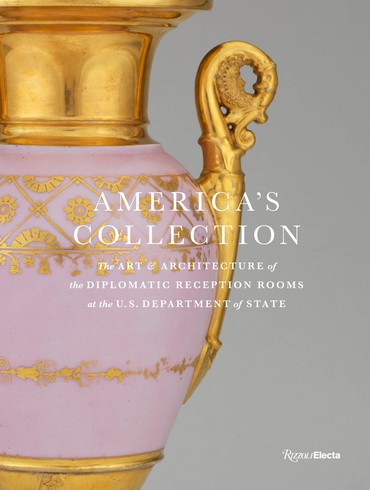

Former Secretary of State John Kerry calls the top floor of the Harry S. Truman Building in Washington, DC, “diplomacy’s penthouse.” He’s referring to the sweeping suite of galleries that house the Diplomatic Reception Rooms. In September, Rizzoli published a tome, America’s Collection: The Art & Architecture of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the U.S. Department of State, devoted to these vast treasures of decorative arts from the early decades of the United States of America. All collections have a mission but these rooms mix purpose with patriotism: they are designed to tell the story of the nation.

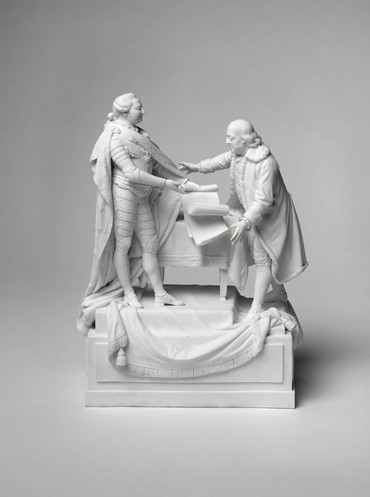

Virginia Hart, the museum’s director and curator, spearheaded the book, and invited other scholars of art to contribute to the stories that explain how portraits, furniture, silver, porcelains, and other arts from the time of our Founding Fathers are used to explore and endorse the American story. The Pulitzer Prize–winning author Stacy Schiff wrote about Benjamin Franklin, the fledgling country’s first diplomat, who landed in France to try to gain support for what was essentially a bunch of rebelling colonials. “Franklin spent nearly nine years in France, all of them in and just outside of Paris. For much of that time he traveled weekly to Versailles, along with the rest of the glittering ambassadorial corps. Not only did they balk at how plainly he dressed—one reported that Franklin, in his drabness, could have passed for a farmer,” she says. “He was the most celebrated man of science in the world; he seemed to have touched down in France like a meteor. His image blossomed on mugs and wallpaper and walking sticks and candy dishes. ‘My face,’ Franklin wrote his daughter, not long after his arrival, ‘is now almost as well-known as that of the moon.’”

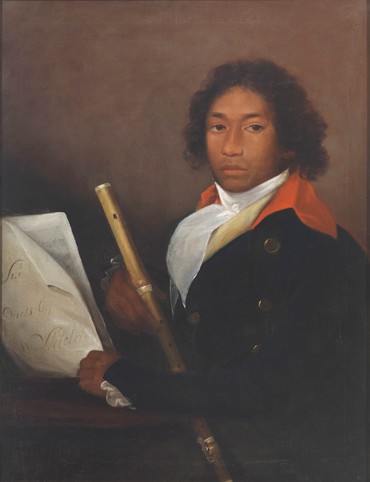

Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, the recently retired curator of American paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, says she’s always intrigued by works that haven’t been completely figured out. “One of the most powerful works in the collection, which was added recently by their director, in an effort to broaden the collection beyond heroes and presidents, is an anonymous portrait of a flutist. It is a Black subject holding a flute and a piece of music,” she says. She reached out to the curators at the Met to source historical data on the piece, which they were able to date to around 1785 to 1810, based on the flute, music, costume, and hair. “I just love mystery,” she says, encouraging viewers to continue to readdress the history of this country.

Derek BlasbergI’ve always been intrigued by the social aspect of art, how looking at something makes you feel. At the US State Department, it’s feeling with a specific intent, the social blending with the political. Has that always been the vision of these galleries?

Virginia HartAbsolutely. It’s a story of America’s history. It’s a story about our founding and our country. The Americana Project began in 1961, but to go back before that: the spaces that we’re in right now [in the Truman Building] were planned in the 1950s and opened in the 1960s, a time when we were the second-largest federal-government building after the Pentagon. The eighth floor was allotted for diplomatic entertaining but no money was left over to furnish the spaces.

DBOf course!

VHSo you can imagine if we’d opened up these rooms for the first time to entertain, how disappointed people would have been with the state of the rooms. That’s why the Americana Project was created, which had the mission that we would furnish these spaces to tell a story of who we are as Americans.

DBJohn F. Kennedy was president in 1961, and as we all know, his wife had an incredible impact on the decor in the White House. How involved was Mrs. Kennedy with this?

VHThat work was happening concurrently: when she was redecorating the White House, we were redecorating these spaces. But we focus our collections on the colonial and Federal periods and the White House focuses its collections on the nineteenth century and on. There is intentionally no overlap between our collecting and between our statements of who we are.

DBWhen did you start working at the State Department?

VHSeventeen years ago! Which is a long time, but I’ve only been here as director for a little more than a year.

DBIs there a part of the job, or an aspect of what you do, that you find especially intriguing? The art or the politics, or melding the two?

VHI’m drawn to the idea of service, and there’s no greater job in the world when you get to serve your country. I love coming to work every day because with the collections there’s constant discovery. I also love just being able to share a good story.

DBSpeaking of service, there’s a chapter on Benjamin Franklin, a man of service himself.

VHI would say he was the country’s first diplomat; we call him the father of the American foreign service, and certainly his presence here looms large, in the rooms that we have named after him and in the likenesses of him that we’ve collected over the years. And there are so many incredible stories about him. Stacy Schiff talks about what it was for an American to set foot on foreign soil and to try to convince a monarch to support rebelling colonies, and what that conversation would have been like. How masterful he really was to do that!

DBThe Truman Building, where this collection is located, looks like a very governmental structure. It’s imposing in its architecture, with square windows and thick gray cement walls. It’s a surreal juxtaposition to take the elevator up to the top floors and find all these treasures.

VHIt is surreal, for me and most people too. You walk into these rooms and you see such a transition into what the architects were able to accomplish within a modern structure. We have here the work of Edward Vason Jones, John Blatteau, Walter Macomber, and Allan Greenberg, architects who were able to choose moments from American architectural periods and reinterpret them in these spaces so that you really do get the full array of experiences in American architecture from 1740 to about 1840. It’s extraordinary.

DBWhat’s the most surprising thing in the book from the collection?

VHI’m constantly amazed at how modern and sculptural some of the pieces are. We often think of eighteenth-century pieces as antiques, yet some of the design here is very modern. We try to present elements of those pieces that allow you to observe the details and begin to see the beauty and the craftsmanship of it all. It’s a world-class collection but it’s also a collection that was entirely donated by Americans. No funds were allocated to the furnishing of these rooms, so everything that you see is a gift of the American people.

DBThat’s an incredible point. The US government did not allocate a budget to any of this?

VHNone.

DBSo how has everything in the collection come to you?

VHWe get gifts from families who have these beloved objects and wish to see them in a museum. Often someone will turn to us, and we are so delighted when we receive those phone calls.

DBDo you know when they’re calling?

VHNo! Most of the time there are really wonderful, surprising phone calls. We also fundraise actively and the fundraising endeavors enable us to go out and to continue to acquire. I got a call last week about an American silver porringer and they mentioned, “We think it’s the work of Elias Pelletreau.” And they gave me the provenance and information and I said, “We actually have one just like it in the collection and the likelihood is that ours are a matched pair.” To think that there’s 200 years of separation and now we’re finally able to see these two pieces come back together is exciting, and definitely not something that the family or anyone in the museum would have ever thought about.

DBI’ve spoken to some of the other contributors to the book and they remarked how, since 2020, art spaces everywhere have been taking a closer look at representation, what it feels like to be an American. From your point of view, how has that experience been reexamined or represented in the museum?

VHIt’s been wonderful to see our audiences asking, “Where am I represented in these rooms?” For us, that means looking at our acquisitions policy and planning and commissioning new voices to begin to tell a more diverse and representative history of who we are. It means working with modern artists. It means engaging with contemporary voices and asking them to rethink these spaces as a celebration of artistry from the eighteenth century up until our present day, and inviting a new generation to tell this story. In the end, it makes it all more powerful and more meaningful, and that’s inspiring to see.

DBFor me, the coolest thing about some of these objects is that they look used. Some of them are worn. There’s a set of spoons that have Paul Revere’s name stamped on the back.

VHAbsolutely!

DBHow does it feel to work with so many objects and works of art that have actually been in the hands of our Founding Fathers? Do you ever have a surreal moment? Do you ever get the chills when you think about some of this stuff?

VHOne of my favorite pieces in the museum is a lap desk, which is sort of a portable box that you would have carried with you to allow you to write correspondence on the go. That belonged to Thomas Jefferson. He would have owned several in his lifetime, but for us to have one of those in our collection is exciting. You feel a closer personal connection to him, seeing the actual ink drops from his pens, the dings and wear and tear. It gives it a sense of history that’s more personal than anything you might read in a book.

DBYou also have more grand desks in the museum.

VHI imagine you’re thinking of the desk where the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, was signed. Of course. Often, when visiting dignitaries come to the museum, we witness really wonderful moments where people are walking through these glorious rooms and encounter this incredible piece of history, which is so important to our own nation’s founding.

DBOf course, most things in DC are politically divisive. What’s the role that the kind of fine art and objects you have in this collection can play in American politics?

VHWe are nonpartisan. In that regard, we don’t make any partisan statements or comments. We serve every secretary of state, no matter what party.

DBJohn Kerry, a former secretary of state, often quotes Benjamin Franklin. Specifically, he retells a story about the early days of our country’s independence and a woman asks Franklin if we’ve got a monarchy or a republic? And Franklin, responded, “A republic”—

VH“If you can keep it.” What a good line.

Photos: courtesy Rizzoli Electra