Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

John Klacsmann is archivist at Anthology Film Archives, New York, where he preserves experimental film and artists’ cinema. Before joining Anthology in 2012, he worked as a preservation specialist and optical-printing technician at the film laboratory Colorlab, Maryland. He is a contributing editor to INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media and runs a tiny tape label, ZAP Cassettes.

Raymond FoyeTell me about your background? If somebody wants to become a film restorer, how do they go about doing it?

John KlacsmannMy undergraduate degree, from Washington University in Saint Louis, is in computer science. I got into film preservation and film archiving at the end of my college studies; I worked in the film archive there as a student. The appeal for me at that moment was the analogue aspect of the work, but I quickly realized that my knowledge of computing was going to be useful in the field too. From there I went to the George Eastman House [in Rochester, New York], now the George Eastman Museum, which has the oldest film-preservation program in the world: the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation.

RFThis program only started in the ’90s, right?

JKYes, as a professional field, film preservation and archiving is quite new. Not that there weren’t film archivists before—there were some very good film archivists before the ’90s—but they were self-taught or they picked it up on the job. There wasn’t a place you could go to study how to be a film archivist back then.

RFWere there legendary figures in the old days of Hollywood, or in Paris, who are revered in the field?

JKOh yeah, sure—someone like Henri Langlois, who founded the Cinémathèque française in Paris in the 1930s. Coming a little later, I immediately think of someone like Jonas Mekas, obviously, but there are many others too. Jonas was a critic and a filmmaker but he also preserved a lot of films. I remember asking him some esoteric technical questions about film once and he followed it all. I had to remember, “Oh yeah, Jonas is actually a very skilled and experienced filmmaker, so of course he can follow this.”

RFIs that true of most filmmakers you’ve worked with?

JKIt varies.

RFDo you think Harry Smith was a good technician?

JKI would suspect so, but you don’t see it so much in Harry’s films if you inspect one of his originals, for example. As an animator, there’s a lot going on, and a lot of his skill would have been in in-camera techniques and on an animation stand. In any case, he clearly knew what he was doing and at a pretty high level, especially considering whatever equipment he would have had access to, which would probably have been pretty DIY or homemade.

RFHow many people graduate from the Eastman program every year? What are some of the other programs in addition to this one?

JKEastman graduates around ten. There are some other graduate programs, one at UCLA and one at NYU. The UCLA one is more library science–based, or at least it used to be, and the NYU program, while they do study film, I think puts more emphasis on video and digital media, whereas the Eastman Museum program is very film-based because that’s what they primarily do there: archive and preserve celluloid films. Not that you don’t learn about digital or video at the Eastman Museum—you have to now—but the history of that program is really in celluloid film. And of course the Eastman Museum is one of the older film archives in the world. They’ve been collecting film longer than most.

RFWhen you think about your peers, people out there like you who are doing what you do, how many of them are there?

JKWell, fewer and fewer.

RFReally?

JKI think so, yes. In the work I do, even if it incorporates digital technology at times, I still believe in making archival film elements and film prints. That’s becoming increasingly fringe, even at the largest, most well-funded national film archives in Europe. Then when you talk about people who specialize in avant-garde film preservation, it’s really just a handful of people. And I know them all [laughs].

RFSo with these new Hollis Frampton restorations you’ve done, they’re referred to as photochemical restorations. That’s a film restoration, precisely the opposite of digital, right?

JKI think you can have a film restoration that incorporates digital technology, and I can explain that, but the Hollis Frampton restorations were all done photochemically, meaning digital was not involved. They were all done with photo-printing and chemistry—exposing film, processing, making contact prints.

RFColor timing.

JKYeah, color timing too. So it’s a very direct way to preserve a film by going back to the original elements and duplicating them in a purely analogue way.

RFTaking the Hollis Frampton restorations as the example, what’s your toolkit?

JKWell, if you’re sticking to analogue and not incorporating digital tools and technology, a lot of the restoration process is about repairing the best surviving film materials—so physically going over the splices, using tape to fix any tears or perforations. That can be very labor-intensive. Then it goes off to a film lab and your tools there are really cleaning; film labs have special machines that can clean film, and you have liquid gate printing, which is an analogue technique to keep scratches from getting printed into the new film elements that you’re producing. Very few labs do this but there’s also a technique called rewashing, where you basically run the film element you’re trying to preserve through the wash portion of a film processor, which happens near the end of a processing machine. That can help to actually physically remove scratches.

RFYou wash it first, or do you wash it at the end as well?

JKNo, you wash it before you print it, before you copy it. And of course you dry it after washing it. That can basically help fuse very light emulsion scratches: the emulsion gets wet, it swells, and the scratches fuse back together. That can be a very useful tool if you’re working with something fairly scratched, which happens quite often. But that’s about it when it comes to analogue tools. And then of course color timing, and that’s a craft, where you’re programming the colored light in the printer to change the color and the density of each shot in the film. That’s a tool too, although there are limits to it, but if you’re working with a technician who’s particularly skilled at that process in the film lab, that can make a big difference in the quality of the restoration. With the Frampton films we were lucky to be able to avail ourselves of the services of Bill Brand of BB Optics, who had been Hollis’s assistant.

RFYou didn’t grow up in the analogue age, did you? By the time you came of age, everything was digital already, right?

JKI grew up going to the movie theater and seeing 35mm prints. On the other hand, I started using a computer when I was nine. So I don’t know—it depends how you define it.

RFThere are a lot of parallels to printing an art book: learning the camera and film technology for the transparencies and color separations; what type of screen you’re using; learning how the presses work. Then you’re on press, making these little adjustments with this big machine, to tease out little nuances all the time. And if you have a press-person who’s sympathetic, you can do a lot. If you get one who doesn’t care, you’re really screwed.

JKExactly the same with film. Especially when you’re dealing with experimental films. Some labs aren’t really familiar with experimental films, might not even care about experimental films, so they don’t put in that extra effort that’s required.

RFOr they may see something they think is a mistake when it’s not, it’s exactly the way it’s supposed to be.

JKAbsolutely. So you have to know who to send what to. Some labs are better than others at certain aspects of preservation.

RFHow many labs are left that are doing this work, say in the US?

JKVery few. In the US there are really only three or four: Colorlab, which is in Maryland. I used to work there before I worked here at Anthology. Then there’s FotoKem, in LA—the biggest lab in the country now. Cinema Arts, in rural Pennsylvania, is a film lab that focused on preservation work relatively early on. Cineric here in New York City is very good, although they’re mostly digital now and don’t have film processors on-site. They’re what we call a dry lab.

RFIf you could improve a film in a restoration and make it look better than the original, would you do that, or would you consider it a step too far?

JKI try not to, but I think sometimes there are opportunities to fix mistakes. I don’t mean when the filmmaker didn’t do something correctly, I mean when an original got scratched accidentally, say. But I think the area where I take more liberties in improving the work is in soundtracks. You can do a lot in sound restoration now that can really improve the quality of the audio.

RFThat you couldn’t do in the old days.

JKThat you couldn’t do in analogue at all.

RFWhy, because of Dolby?

JKBecause of digital technology, yes, you’re able to clean up or excise certain parts of the track. 16mm sound in particular is quite bad, so if you can bring out the soundtrack and make it a little bit more legible in the restoration, I think that’s generally admissible. You don’t want to go too far, it can’t be sparkly clean, but if it makes it more intelligible I think that’s a good thing. What I’ve always really wanted to do is make a Dolby digital track on a 16-to-35mm blowup so that the sound that was carefully restored can be played back digitally on a 35mm film print. The problem with that is you have to pay something like a $5,000 licensing fee to Dolby to even print one of those tracks. So I never do that, because I’m only making three or four prints. It’s not really economical to make a digital track on the film print, which is unfortunate because that technology is pretty good and you could still make a Dolby digital track that’s mono, like the original. But the audio would be very clear.

RFAre there any other proprietary technologies that you encounter in your work like that?

JKThat’s the biggest one I can think of. Especially when it comes to working with film. That’s the good thing about analogue, it’s—

RF—free.

JK—it’s kind of hard to lock down.

RFInteresting. You worked on the restoration of Michael Snow’s Wavelength [1967]. That must have been a really exciting experience.

JKIt’s still in progress. We need to finish the sound restoration, which is actually quite complicated for Wavelength. It might even be more complicated than the picture restoration, which is basically done. Yeah, it’s thrilling to work on Wavelength. But do you know what led to me restoring it? Michael was in town in 2019, and they were showing Wavelength at the Museum of Modern Art. I went to the screening because Michael was going to be there, and as I was watching the 16mm print I was thinking, “Oh fuck, I have to restore this. Now I have to deal with this. This is my problem.” Not because the print they were showing looked bad or anything, but just because it was a film that was badly in need of preservation.

RFIt’s so important.

JKExactly, and the original’s not in bad condition but it’s just a film that really hasn’t ever been restored. There are negatives, Michael made negatives, but he also made lots of prints from them. So there’s not really a good archival negative of that film. Watching it in 2019, I had just finished restoring his 1969 film <—> (Back and Forth). I realized, I’m now going to have to restore Wavelength, and it’s just a lot of responsibility, and it’s daunting. That’s what I was thinking—this is a lot of responsibility, this is a difficult task, and it has to be done well. A lot of people are going to see this restoration.

RFA lot of work and a big headache.

JKA headache, but also an honor to work on. Just the responsibility of restoring what I consider to be the best film ever made.

RFSame here.

JKI don’t take it lightly. Handling the original A and B rolls was very fascinating. I got to map out the entire film. Every splice I logged and every film stock I logged. I made this map that breaks down Wavelength in a way that maybe doesn’t exist anywhere else, except for maybe with Michael, I guess. It’s fascinating because he used so many different film stocks, like every film stock went into it. It has color reversal, it has black-and-white reversal, it has color positive, color negative, Kodachrome, Ektachrome, Kodak, Agfa, DuPont, Ansco . . . all these different stocks and manufacturers. So when you inspect the original A and B rolls where the superpositions aren’t there, you’re seeing both sides of what he double-exposed later in printing.

RFAnd often using film contrary to a way it’s supposed to be used, using an outdoor film indoors and vice versa.

JKYes. And also cutting color negative into the film so onscreen it appears as a negative, so it’s sort of an orange-based flipped section of the film. So yeah, he was doing a lot of unusual and interesting things. It’s a really fantastic thing to try and unpack, and it’s all very impressive. I have even more respect for the kind of editing work that went into it now. Because Wavelength is often thought of as one single slow zoom, which it isn’t. It has so much careful editing in it.

RFI want to ask you about the Harry Smith restorations. What was that like to work on, and how many of those films did you actually have original elements for?

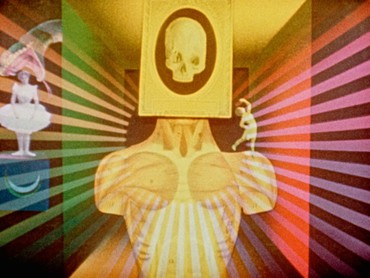

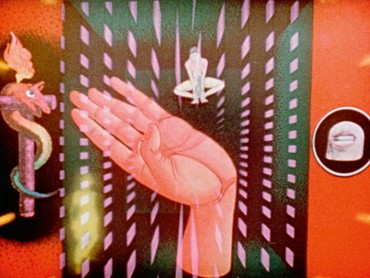

JKWorking on Harry’s films was a dream come true. It’s hard for me to even believe that I had any part in his films surviving, because they were really the first experimental films I ever saw and appreciated. To handle them and restore them is an honor. Since the 1970s, Anthology has had almost all of Harry’s original film elements. And when he was working on films through the ’70s and into the ’80s, they were deposited here immediately. So contrary to popular belief, the originals of most of Harry’s films survived, certainly the later ones.

RFBut not the actual painted ones, do they?

JKWell, Early Abstractions [1946–57] is kind of all over the place; it’s really seven short films that he put together [around 1964] years after he had made them. So when he put together the compilation, for some of them he used the camera original, for some of them he just used a print. It varies across the compilation. In the first three films, which are the hand-painted ones, what’s cut into Harry’s compilation is actually the 16mm Kodachrome reductions that he made from his hand-painted originals.

RFWhich were on 35mm.

JKWhich were 35, and don’t survive. I consider those 16mm Kodachrome reductions the originals because as far as I know, Harry never showed those early painted films on 35mm. They were immediately reduced to 16. You can look in [SFMOMA’s] Art and Cinema program notes, where they first showed, and it’s mentioned in one of them that he was waiting for the reductions to come back from the lab before they could be screened in the series. So I’m fairly certain that those are the original 1940s reductions he cut together in the Early Abstractions compilation. The thing that I realized when I handled Early Abstractions and preserved it is that there are splices within those reductions too, so they’re edited. Throughout the films, Harry often painted over the cement splices to hide them. So he’d rephotographed the painted animations but then he was painting on the copies too, which you don’t really realize when watching because they blend in so naturally. I had no clue until I inspected it and I realized, Oh, there’s painting on this physical film that I’m handling, it’s not just printed in. So that actually limited what we could do photochemically: no cleaning, no rewashing, no liquid gate printing. Because we couldn’t remove the paint that Harry put on those physical 16mm Kodachrome reductions we were working from.

RFThat’s just a given as a preservationist, you cannot do that.

JKWell, you could, but if you did, the paint would come off before you duplicated it . . . and that would be bad. So the Early Abstractions restoration is a little scratchier than I would like. But that’s the way it is, since we couldn’t use any of those analogue techniques to take the scratches out because of the paint that Harry put on the film to hide his splices.

RFThat’s always a given in art conservation: you don’t do anything that cannot be redone later on.

JKIt’s similar in film preservation, although the difference is, film preservation is all about making duplicates. We’re working with the original object but the goal is actually to copy it, whereas in art conservation you’re actually painting on the painting, the original object. We’re not doing that. But yes, you wouldn’t want to use a technique that would be destructive, and dealing with painted film is a great example. That comes up all the time in experimental film. You have to be really aware of what the film is, and that’s really only revealed by handling the film and inspecting it carefully.

RFIn art conservation, if you have a watercolor, you don’t put it on a wall where it’s going to get lightstruck. Do you have that problem with film, where it’s going through a projector and you’ve got light coming at it? Does that ultimately affect the film?

JKWell, in film preservation we’re almost always projecting new copies. So if something got damaged or it faded, we either have another print or we could make a new one, at least right now we still could. So there’s a little bit less risk. But a film really won’t fade in a projector because each frame is not really exposed to the projector’s lamp for long. Theoretically it could cause fading, it’s getting a lot of light from the projector lamp, and if you left a filmstrip outside in the sun it would fade pretty quickly. But in the projector it doesn’t really happen. It’s going to fade naturally over time more than it will via projection. And when film’s not being shown, it’s stored in a can in the dark.

RFThat’s a big part of preservation, proper storage, right?

JKHuge part. In film archiving we’ll refer to that as conservation, because you’re conserving the original object or master. The storage environment is critical. Besides duplication, that’s how you make film survive.

RFDo you feel like you’re in a race against time with your profession?

JKYes [laughs].

RFSo you know while you sit here that things are actively degrading and falling apart, very important things.

JKYes, and I also know that we’re not going to be able to make new film elements of every film in Anthology’s collection. There’s not enough time or money to do that. And that’s the case with most archives, even the ones that are the best funded.

RFSo you have to make decisions about what you save and what you don’t.

JKYou have to make decisions about what you duplicate and what you don’t. In the future, scanning every film in a collection is a goal that I think will be doable, with enough time. Whereas preserving film in a traditional sense eventually won’t be possible anymore. They’ll stop making film before we get to all of them. For that reason I’ve been trying to focus more on that aspect: producing new polyester-based film elements. My approach is to do as much of it as we can, right now, to preserve films on film. Many other archives don’t take this approach anymore, but I think we should, because now it’s possible and eventually it won’t be.

RFBecause you foresee the day when Eastman Kodak will just cease to exist.

JKThey’ll stop making film. There’ll be no labs to do the work. There’ll be no lab technicians who know these processes.

RFWhen do you think that will happen?

JKIt could be ten years, it could be twenty years, it could be tomorrow. I focus a lot more on film preservation than mass digitization. I feel like we have from now until forever to digitize while we have a much more limited window to make film copies, so let’s do that now while we still can. We won’t be able to preserve all the films we have on film, but the more we can, the better. The preserved films will become even more valued and cherished once it isn’t possible to make new film elements anymore.

RFIn recent years have you noticed more of a sensitivity on the part of young people to analogue media?

JKI think so. I think especially since COVID. At Anthology’s screenings, especially of avant-garde classics and preserved films, the attendance has never been higher. It’s not exclusively young people, but there are a lot more young people than there used to be. And I think that’s because more and more there’s a lack of film prints being shown in cinemas. I mean we’re very lucky in New York City, because actually quite a few repertory cinemas still project film here. But I think people appreciate it because they realize it’s special and increasingly rare. And if you come to Anthology and you see new restorations, you’re essentially seeing brand new film prints. So they’ll never look better. It’s a real opportunity.

RFI believe that digital actually blocks a lot of the metaphysical and spiritual content of the work. I think there’s this physicality, but then there’s something else, which is presence. I think digital blocks a lot of those vibes.

JKI 100 percent agree. When you’re doing a photochemical preservation, there’s a really direct connection to the original object, literally. It’s been physically duplicated, reproduced. There’s a lineage, and it goes right back to the original. And if you’ve done it well, it’s representative of the earliest times that work was shown. To a dedicated group of people, this is essential to experiencing the work.

One time when I was walking around Anthology with Jonas, he was being interviewed by a German journalist, who asked him, “How do people know to come here? Don’t you want to reach more people with these films? You’re only getting a small number of people here.” And Jonas said, “Well, you don’t buy poetry at the airport.” I always think about that. Not everybody’s going to appreciate avant-garde film, but the work is still important and has a place.

RFYeah, you have to be fine with a small audience when you work in these kinds of fields. How many copies of the Tractatus did Wittgenstein sell? Something like eleven. T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, W. B. Yeats, all their first books were self-published in editions of forty, fifty, seventy-five copies, and they didn’t sell many at all. So there’s nothing wrong with a small audience.

JKWhen you’re archiving and preserving, you know that you’re doing it for the future, really. It’s about the present to some degree, but really it’s about the future. So there’s some hope that this stuff will survive and people will still have access to it, and will still be interested in it, many years from now.

RFDo you have personal or sentimental favorites among the films that you’ve restored?

JKMaybe some of Ron Rice’s films: Chumlum [1963], The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man [1963], and Senseless [1962]. The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man restoration is a great example of the amount of money it costs to restore a film, and how many times more it costs to restore a film than what it cost the filmmaker to make the film originally. It costs far more to restore than the film has made and ever will make at a box office. So when you get the opportunity to preserve a film like that, you really do feel good about it. There’s no commercial incentive for this work to survive, whereas in Hollywood-film preservation, there is. And that’s why preservation gets done in Hollywood: they duplicate and preserve their films so that they can continue to make money off them; the films are seen as a financial asset. Ron Rice’s films are assets but not financial ones, they’re cultural. I have a lot of respect and gratitude for Martin Scorsese’s foundation the Film Foundation, and for the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, which supported the restoration of a long film like The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man, which is just a bonkers insane Beat experimental film that’s brilliant but, you know, just taking care of it is a financial burden for the archive. The film will never make any money back in its entire life, restored or otherwise. It isn’t about making money anyways.

RFAnd this is just because those filmmakers, Scorsese and [George] Lucas, saw these films when they were young and were inspired by them.

JKAbsolutely. They understand the cultural importance of experimental cinema—that it’s not only Hollywood, it’s not only narrative film. It’s like poetry: there are novels and there are poems; we’re preserving the poems, and great filmmakers understand that, having been inspired by them.

Please consider becoming a Preservation Donor or otherwise supporting Anthology Film Archives via their website: anthologyfilmarchives.org

The “Gagosian & Film” supplement also includes: “Adaptability,” “Not Running, Just Going,” “Whit Stillman,” “Sofia Coppola: Archive,” and “On Frederick Wiseman”