Olivier Berggruen is a writer and curator based in New York. He serves as artistic adviser to the Gstaad Menuhin Festival in Switzerland and his book Formes du désir: une brève histoire de la collection d’art will be published by les presses du réel, Dijon, later this year. Photo: Nadia Zeghmouri

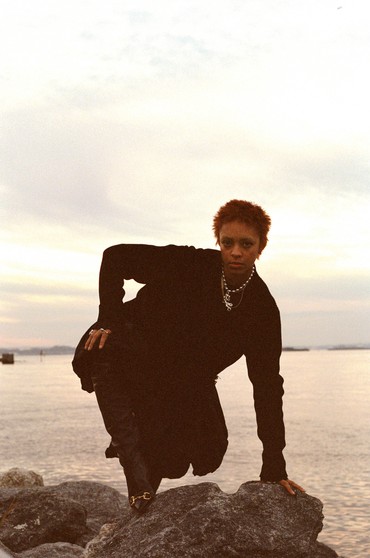

Kelsey Lu is a singer/songwriter, producer, composer, poet, performance artist, and classically trained cellist born in Charlotte, North Carolina. Their practice flows at the intersection of visual art, performance, healing, and music. Their recent projects include the score for Savanah Leaf’s feature film Earth Mama (A24/Park Pictures), which premiered at Sundance 2023 and won the San Francisco International Film Festival Audience Award; starring in and the score for Janicza Bravo’s film House Comes With a Bird (2022), which screened at the Venice Film Festival. Photo: Clifford Prince King

The Lucid: Transfigured Night

It was getting late, but I thought I had just enough time to make my way to a musical performance in East Berlin, somewhere past Alexanderplatz along the Spree River. As I passed under a cerulean sky of silvery clouds, Google Maps proved inaccurate; eventually, on a side door in an industrial area, I found a small sign announcing the venue, a new performance space called Reethaus. I walked through the front entrance of a nondescript building, exited the building through a facing door on the other side, and then followed a narrow wooden path toward what looked like a ziggurat-shaped mound. On the far side I could see the Spree. It was chilly, with the sun emitting its last rays of light. No one was there; I had miscalculated my arrival time.

When I checked in, I was asked to leave my phone in a locker and to don my shoes for felt slippers. Once I reached a terrace overlooking the river, a waiter who looked like a secular monk offered me some delicious hibiscus/cacao juice, which was refreshing. People started gathering. After a long day of travel, I found myself in a haze, as I saw a crowd of ghostly silhouettes flickering in space and bits of skin or jewelry or nylon clothing shining in random choreography. My friend Annette came up. I had seen her a few days earlier at a music recital in a baroque palazzo in Venice; although I knew she lived in Berlin, she seemed out of place here—she is a classical violinist, and I could not imagine her in a temple of experimental music. An intrepid venue for music, she said. But isn’t that what Berlin is about?, I thought to myself. Was this place trying to be too edgy? I wondered.

We waited for some time; I talked to Klaus and a few other curators and artists I knew vaguely. Then at dusk Lu appeared, silently walking in our midst, as if sleepwalking, in a diaphanous white dress and white platform boots, with cropped hair dyed blonde, their eyes lifted hypnotically toward the sky. Slowly I started paying attention, opening myself to what was unfolding before me.

The Lucid: A Dream Portal to Awakening, by Kelsey Lu

It was all so quiet. We followed Lu into a zenlike temple, the inner room of the Reethaus—a monastic space with various tiers of seats, each seat filled with its own cushion. I sat on the floor on the edge of the stage. Lu reclined on a bed, or rather a white mattress covered in sheets and a duvet. The gentle murmur of cicadas was relentless and layered with electronic sounds. Lu then reached out for their cello, played a forlorn melody over the cluster of sounds, and started singing.

Only the stage was lit, and as the music unfolded, long layered chord progressions created vast loops of sounds within a space of unfathomable dreams. It had intonations of dronelike eastern ragas, classical cello, and Black churches in the American South. Yet it had its own distinct pitch. Lu moved slowly, haltingly. The reconfiguration of the body’s language into seemingly natural but vertiginous directions provided a sense of exhilaration as I observed their movements, while realizing that this unfolding was a natural choreography in which time could seemingly be suspended and space conquered.

They started crying, wailing, the paroxysm of recalling that space is a void, yet it felt alive, caught between dreams and the realization of being caught in the prison of oneself. But not entirely: the shouts were a call to the unknown, a shared sigh that resonated with a night of veiled stars, yet enough to create seismic waves. A cry from the savage heart. And then the wailing slowly gave way to a reverie ending with the sounds of cicadas, and then silence, like a child returning to her mother’s womb.

In Stillness We Dream

The lights came on, followed by applause, though I was still in a dreamy state, like someone floating in a sea of salt, ecstatic and in disbelief. Lu’s friends MJ Harper and Kandis Williams came onstage, quietly starting a conversation that led to a gentle interplay of three friends moving around the beautifully disheveled bed, their bodies in sync, at times interlaced, playful, enveloped in the afterglow of the performance. They then treated us to a cup of sweet sake.

As we returned to the terrace, Lu mingled with the audience, glowing in their white dress, friends gathering around them, hugging them, teasing them, laughing. I chatted with them briefly, telling them about waking up to the sound of cowbells before coming to the shores of the Spree. The skies were faintly illuminated by distant stars, the moon barely visible behind hesitant clouds. It was a perfect day.

—Olivier Berggruen

With thanks to Kia Corthron and Mebrak Tareke for their comments.

Olivier BerggruenLu, after your performance in Berlin, I found myself thinking about how a sudden silence leads to something, and how all the different layers between transparency, opacity, and various complexities build up in your music. Could you speak about the process, and how silence plays into your work?

Kelsey LuWell, even though I’m from a city in the South [Charlotte, North Carolina], the South is still the South and the fabric of time and of sound are unique there. Sitting in silence and listening to my thoughts was a big part of my childhood, just being in the backyard, being within dirt, digging into dirt.

OBWhich ties into the visual aspects in many of your works. With This Is a Test, shown at the Shed, New York, in 2021, for example, there was this mound around which you were performing.

KLThe roots. Yes, and for my recent performance at the [Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York], I flew home to North Carolina and went to my childhood backyard and I dug a hole and collected dirt to bring with me for that piece.

OBOne of the things that struck me was the sense of ritual in your practice. Do you distinguish between the profane and the sacred? What you’re doing may not be religious in the traditional sense, but nonetheless there is a very strong spiritual dimension.

KLWell, thank you [laughs]. Music is spiritual. There’s spiritualism in making music, in creating a space where people all come together, all listening to the same thing. We’re applying the meaning of what we’re experiencing in different ways. For me, music has always been the constant; even as I questioned or departed from the religious notions I was raised to believe, my faith in music hasn’t gone away. I clung to it so hard, it became my religion.

OBWhen I first heard your work, on your albums Church [2016] and Blood [2019], I thought of John Coltrane and Alice Coltrane. Do you see their work as part of a particular lineage that you relate to?

KLDid you know John Coltrane is from North Carolina as well? But yes, beyond that geographical relationship, I believe that there’s also a lineage of vessels, where I, as a vessel, also fit in. By saying that, I’m referring to a magic that moves through us, that we hold for a time—when we can pull something off in a particular moment in a way that may never happen again. I have rituals and practices in my day-to-day life that tether me to an existence on this plane, and allow me to be able to do what I do.

OBDo you write down your dreams?

KLI do. Not always, but I’m drawn to the practice: I feel like you’re stepping into your subconscious in a way, or you’re accessing memories of the past, present, and future—or even of you in this lifetime, or maybe in a past lifetime. I also think there’s collective dreaming. To not think that we’re affected by the myriad of people around us is pretty limiting. Just as I’m able to send an email to somebody on the other side of the world, I think we’re able to access each other’s memories in some ways.

OBAbsolutely. There’s this Platonic dialogue called the Meno [402 BC] that speaks about anamnesis, or the recollection of events from past lives, or at least prelife. In Plato it’s a kind of oddity, but this very wonderful and beautiful dialogue seeks to understand why certain things that are so familiar to us are. We have certain knowledge of or affinity for certain things because our correspondence to them predates our birth.

KLI believe that.

OBYou integrate so many different elements in your practice. Whether it’s visual, auditory, tactile . . . you’re able to embody something like a total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk. Somehow the old division or separation between the arts is something that I find a lot of younger artists don’t believe in anymore; likewise, I think the old parameters of genre are being abandoned. While you do utilize tradition—musical notation, your preferred instrument of the cello—it doesn’t seem like you ever limit yourself to an orthodox manner of engaging those elements: you find ways of plucking the strings that may not be integral to the European tradition, or you have ways of playing the piano as Thelonious Monk did, in a completely novel way.

KLAnother North Carolinian [laughter]. Well, yes, I feel a strong urge to challenge what everyone seems to be going along with. I’ll admit I have a rebellious streak; not going with the flow of what I’m told is my way to go about something. But this isn’t just resistance for the sake of resistance—I like challenging myself. I like challenging an idea of what one person is capable of. I think we’re capable of so much, while also being ants—we’re all tiny little ants on this planet, but ants are capable of holding a lot of weight.

I think a lot of people are insecure with themselves. And I think that can come from being told how you should be or what you should be doing. It can be scary when you’re thinking for yourself creatively. I know that when I was in college, I was like, “I want to take all the classes. I want to take dance class. I want to take acting. There’s so much I want to do.” And many people around me really shunned that aspiration, shunned the idea of someone being capable of more than one thing: you should just focus on the one thing and that’s what you should be doing so you can master that one thing. And I understand that, but I just can’t do it.

OBHow did the project in Berlin, The Lucid, come about?

KLI dreamt it. But the journey of the music itself was part of a larger piece, an eight-hour-long piece that I made last winter. I composed it originally for a sound installation in Sydney, Australia. I never got to experience it, because at the time I was working on the film Earth Mama [2023].

OBWhich I haven’t seen.

KLYou can stream it.

OBAll right, I will.

KLSo both of those things were colliding at the same time; I was working on this film composition and this sound installation simultaneously. And it was interesting how they were feeding into one another, in a way. Working on the soundtrack for the film, and seeing, continuously seeing, the same scenes over and over and over again about motherhood, the womb, healing, grief, and loss, while also working on this eight-hour-long lucid-dreaming piece was impactful—all of this while I was also practicing lucid dreaming. Birth and loss and grieving were a big part of my dreamscape.

OBI understand that the particular iteration for Berlin—at MJ Harper’s invitation—came together quickly. Was that a source of stress?

KLI wasn’t sure that I was going to be able to make something in such a short amount of time. Definitely. But as I was practicing over the summer, going and sifting through darkness, I was able to accept and trust my process in a way that felt right. It takes a lot of trial and error for a person to understand what their process is, especially if it doesn’t look anything like anyone else’s.

OBIt’s forever. I just turned sixty and I’m still struggling with issues to do with my writing. This process never ends.

KLIt doesn’t. But for this performance, an important moment carried me along: I traveled to Marseille for a friend’s birthday, and while I was there I was meditating on the roof and then I opened my eyes and I was looking out at the sea, and it dawned on me what I needed to do. This word kept coming up in my meditation: “Sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, rest, rest, rest, rest, rest, rest, rest, rest.”

OBI worked for many, many years on the work of Yves Klein for a retrospective at the Guggenheim Bilbao; it took him considerable time to arrive at a new project and it wasn’t always a conscious process, it was something that needed to be decanted like a wine over time. But once the idea was there, the implementation of what he envisaged was easy and painless. It’s like a lifetime of experience that’s concentrated in a drop of water.

KLExactly. When I realized what I needed to do for the performance, I realized that I already knew it. I realized that it was already there, it had been there.

Photos: Clifford Prince King