Whit Stillman is the writer/director of five films: the Oscar-nominated Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), The Last Days of Disco (1998), Damsels in Distress (2011), and the Jane Austen adaptation Love & Friendship (2015). He started out in journalism and book publishing and has written two novels related to his movies.

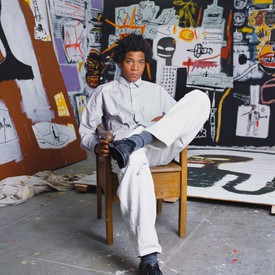

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Coiled and tender, a measured yet barbed looniness to suggest comedies from the straight-backed nephew of Preston Sturges, surrounded by the sparkles of Ernst Lubitsch: to describe the comic temper of Whit Stillman is a tall order. Important: it is not wit (no “wit/Whit” jokes please), nor do his films propose anything as stuffy as a philosophy—unless one sees a dance craze as the basis of a system of life. Maybe [Friedrich] Nietzsche should have made like the coeds in Stillman’s Damsels in Distress (2011) and done the Sambola. I still don’t know why I so adore his films. In Metropolitan (1990), Stillman’s debut, a plucky bourgeois striver sees a pack of elegant Easterners—from the Upper East, you could say—emerging from the Plaza. December: the debutante ball season, always to be attended each year, is swinging. What do I, the Angeleno, know about deb balls? Nil. But I know a thing or two about the strive, the yearn. I know what it is to not know, to be an amateur. And this is the joy of Stillman’s universe: his films take up the gaze of the curious amateur, the innocent abroad (a Westerner in the East), the slight outsider peering ever so slightly in and gaining might—a might of vision, a mighty heart.

But what fuels the striving of these doomed bourgeois in love, these boogying disco dukes-twice-removed, these American gentlemen in Spain? It would be vulgarly on the nose and just plain wrong to equate Stillman with his characters; naturally, though, they don’t materialize out of thin air. And when I speak to Stillman in a noisy Paris bistro across from the Musée Picasso, I am not surprised to find a lovely precision in his conversation, which, who knows, could form the seeds of his next work: new installments of The Cosmopolitans (the Amazon show for which, in 2014, he made the pilot) on lonely Americans in Paris?

The occasion of my talk with Stillman was the publication, by Fireflies Press, of a book on the director, Whit Stillman: Not So Long Ago, with essays by Serge Bozon, Beatrice Loayza, Nick Pinkerton, and others, as well as a comprehensive career-spanning interview with Stillman that I highly recommend. Given that in mind, I figured that our conversation could entertain another angle into his work: the question of influence. (Though with no Harold Bloom-ian anxiety!) We talked about the influences of his early life, his first experiences with the cinema, how he got his start in the Spanish film industry, his literary inspirations, and how he cultivates his ear for dialogue.

—Carlos Valladares

Carlos ValladaresDo you remember the first film you saw in a cinema?

Whit StillmanWell, maybe this is a recovered memory, but I think my first memory was when I was about six, seeing Bambi [1942]. I believe it was Bambi but I remember also seeing westerns. I was born in 1952 but I think there was a sort of 1957, 1958 rerelease of Bambi, so it would have been then. And we had a decent cinema in our town. I think it was called the Storm King Cinema because we were just below Storm King Mountain, in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York. The theater had twenty-five-cent children’s admission, seventy-five-cent adult admission, and the best thing of all, a real treat for us was the Saturday before Christmas: they would do a matinee program only of cartoons, and all the kids in town would go to this. It was a madhouse of people screaming. I actually wrote about it for the Guardian. My parents didn’t seem to care for it, but for us it was a great experience. All cartoons.

CVAnd related to that, I notice a lot—I mean, just to jump ahead to Damsels in Distress, I notice a very heavy Looney Tunes-ian, almost Frank Tashlin-esque influence to that film, a playful elasticity that’s somewhat in the earlier films but really jumps out with Damsels.

WSThat’s interesting. No one’s mentioned that, but I think it’s true. We really loved that and we read about Tashlin; he was in the pantheon of [the film critic] Andrew Sarris, who wrote about him quite kindly.

I have one funny story about seeing a French film on one of these independent New York stations, it was probably dubbed, and there was an absolutely beautiful woman in the film. A period film. I wanted to look at the credits to see who she was; I looked at the names and I decided that the beautiful woman must be called “Alain Delon.” So I was in love with Alain Delon for a long time! And in retrospect I think it must have been that Alain Delon, Romy Schneider film set in Vienna in period [Christine, 1958], and it was really Romy Schneider I had fallen for.

The cinephile in our family, I suppose, was my mother. In those days she’d take us to the “well-thought-of” British films. Both of my parents were very much into Ealing-type comedies. My mother took us to see Genevieve [1953], my father took us to see The Mouse That Roared [1959]. There was a British comedy about stealing mink coats, Make Mine Mink [1960], with Terry-Thomas and a great cast. I remember my mother took us to The General [1926] by Buster Keaton with friends of mine, and we just adored it. It was great to see a silent film. And then I remember Marriage Italian Style [1964]—which, I mean, I was really a prudish, priggish kid, I’m surprised that went over well with me.

The big cinema experience was Saturday afternoons with my father, seeing the big war films: The Longest Day [1962], Zulu [1964], 55 Days at Peking [1963]. But then things sort of turned south for me in cinema. I kind of didn’t like what happened in cinema in the 1960s. My tenth birthday party was the long version of Lawrence of Arabia [1962], in its road show presentation, and we died of thirst during the film. My friends and I were by the water fountain almost the whole time. We were psychologically oppressed by the desert scenes. And we kind of hated the film, because the psychological weirdness was not for ten-year-old boys of that era. I remember seeing, with my father, [Alfred] Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain [1966], and there was a really disturbing trailer for some semiporn Swedish film beforehand, and it really bothered and upset me. So I started getting a little skittish about cinema.

CVWas yours an environment in which great cinema and great literature went together, no distinction between the two?

WSI suppose the good-book influence on me was my elder sister. It was my elder sister who turned me on to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Jane Austen. That’s pretty important. And then at Harvard we had a very good teacher, Walter Jackson Bate, who was a specialist in eighteenth-century British literature and Samuel Johnson. He was very influential and popular, a brilliant lecturer. I took his course, I’m not sure if it was history of criticism or criticism—he published a wonderful anthology, Criticism: The Major Texts [1952]. So from that I loved the early critics, [William] Hazlitt, people like that. And over time, I guess I fixated on the second half of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century as sort of my affinity periods.

CVOne of the best scenes of Metropolitan, of course, is Tom’s explanation that he prefers reading the introductions to Jane Austen novels to reading the actual novel. It’s presented as a satirical jab, and it never fails to get a big laugh from audiences who watch Metropolitan in cinemas, though I wonder whether you yourself would sign off on the preference.

WSI’m totally that way. I love reading criticism about things. For instance, most [Charles] Dickens I find off-putting. I mean, I think Great Expectations is still a great book, but I guess—did Henry James call them baggy monsters?

CV[Laughs] He did, yes.

WS[Anthony] Trollope’s baggy monsters I’ve gotten to love, but Dickens’s baggy monsters I don’t. But I love reading criticism of Dickens because I love reading about the characters and the comic world. There’s something aesthetically undisciplined about [Dickens’s novels] now. But with a lot of things, it’s not like you can really fault them, it’s just there are other things you’d prefer to read, you know? If I have to read, I prefer to read Trollope or Austen or George Eliot. And I think there’s a hugely reactionary tendency for people to think that one has to have some particular orientation to writers of your own sex or background or whatever. Because the living writer I most admired—and whom, when I got out of college and was trying to be a writer, I got a chance to meet—was Isaac Bashevis Singer. I wrote a magazine cover story on him as the world’s greatest living writer when he was still alive. Shortly after that, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature, so it made me look good to the magazine. I don’t have a huge overlap with Isaac Bashevis Singer in some ways, yet I have a huge overlap in other ways. The same with Jane Austen, and George Eliot too. I mean, all this thing of women writers, male writers—

CVThat thinking may be precisely the reason why I think your films have such cross-appeal in terms of gender and race and class lines and so forth: your characters are precisely imagined yet expansive. And with Dickens, you have the reliance on the stock type, perhaps, which isn’t really what your cinema is interested in.

WSOn a sense of human fairness and fair play, of looking at the characters at eye level, it sort of bothers me, that kind of New Yorker fiction of a certain period where they’d write stories about inarticulate working-class types, then pat themselves on the back for their subject matter, when, I don’t know, they weren’t really entering into those worlds at our level. It’s a kind of implicit looking-down-upon.

CVThe logic and look of musicals clearly hold a privileged place in your work.

WSI love musicals! I love musicals, and I felt I was following in a family path because my father also loved musicals—it’s part of our family schtick, we would go to musicals. We got to go to Europe when I was ten, and in London we saw the original production of Oliver!, which was fantastic, and it had a wonderful performance by Davy Jones, who then became one of the Monkees. And then he came over to New York and was in it, and we saw it again. Our favorite show was about [New York] Mayor [Fiorello] La Guardia. My father was in politics and we liked Mayor La Guardia, and there was a show called Fiorello! [1959] based on the memoirs of one of my father’s friends, Ernest Cuneo, who had worked for La Guardia.

After I graduated from college, our favorite uncle, Ted Riley, took us to see Top Hat [1935], with Fred Astaire, at Radio City Music Hall. A beautiful showing. But then there was a New York Times article about the Fred Astaire movies of that period, which said that people don’t wear white tie and tails anymore. I got upset at this because I knew that at the debutante parties they sometimes did. So I wrote a letter of protest to the Times, and I appointed myself the executive director of the New York Committee to Save the White Tie. And that got published. It was a funny letter.

CVDid you see yourself, maybe in your Harvard years, as a filmmaker who was adding to the canon of American arts and letters by way of the image?

WSI think the ambition came when I had so much trouble writing fiction in college. I was really struggling with it, and I hated being alone. I hated the idea of the writer’s life. And I guess I was maybe too much immersed in all Fitzgerald’s struggles. And there was a wonderful group of television situation comedies in that period; they were really humanistic and delightful. One of the things that sort of bound us together at the clubs at Harvard—we didn’t call them fraternities; actually Damsels in Distress has a sort of reference to this—was whatever the big night was for sitcoms on NBC or whatever channel. We would watch The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show. What became my favorite was Sanford and Son, with Redd Foxx. Did you ever hear of that?

CVI loved Sanford and Son!

WSIt was really funny. I didn’t really like Archie Bunker [All in the Family]. It’s sort of too critical and too obvious. But Rob Reiner, one of the spark plugs of that show, became the guiding spark for Castle Rock, the company that was so crucial for me.

Around this time, two things were happening. John Sayles came along with Return of the Secaucus 7 [1979], which showed it could be done: someone could essentially write a short story and get it on screen and have it distributed. And at the same time, I got my break into cinema through the Spanish cinema industry in 1980. They had an indie comedy scene going in Madrid, with Fernando Colomo and Fernando Trueba and other filmmakers, and I got into their cinema world. It was way ahead of where we were, and they were just directly channeling the comedy side of the French New Wave.

I was really liberated by what [John] Sayles did in terms of production, but except for Brother from Another Planet [1984], which is more comic, his cinema is not in my area.

CVMeanwhile, you’ve said in the past how much you admire Jim Jarmusch.

WSWhat I so admire about what Jim Jarmusch did was that Stranger than Paradise [1984] is an absolutely minimalist film in terms of means and elements, and yet it’s really delightful, really funny. And that’s remarkable; it’s incredibly helpful. I mean, there are probably people who make a lot of films that you feel very close to, but to see a person who brilliantly solves a problem and in doing so helps everyone else—Oh, this lock has been cracked, there’s a way to open this door. Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It [1986] was one of those doors too. I felt he got a raw deal on School Daze [1988], which I really liked, and I think that in a way, Damsels in Distress is an answer film to School Daze.

CVWhere did you cultivate your precise ear for dialogue?

WSI have no idea. I remember a really key time, trying to write the script for a Hasty Pudding show at Harvard. There was a book on the Marx Brothers films called Why a Duck?: Visual and Verbal Gems from the Marx Brothers Movies [1971]. And I think it’s their pun on “viaduct”—someone’s talking about a viaduct and they start asking “Why a duck?” It’s all about the dialogue in Marx Brothers movies. Then I think the other person who influences everyone is Oscar Wilde.

CVI like what you write in this new book on your work, when you’re reviewing the collection of Preston Sturges’s screenplays and you describe them as $20 film schools, you can learn so much through just reading them, rather than spending so much going through the system professionalizing as one does now.

WSYeah. For me, one thing that was super helpful was somebody published the screenplay for The Big Chill [1983] in facsimile format. I had no idea what a screenplay should look like. So I had this facsimile, and The Big Chill is sort of related to Metropolitan. It’s the idea of a group of people sort of stuck together—

CVRight. The Secaucus 7 is also that kind of the ensemble getting together, and things aren’t the same as they were but we’re trying to make a go of it.

WSYou know, the legendary story that Damsels in Distress is based on has to do with a group of girls at Harvard after my time, I never knew them. They were called the Shalimar Six.

CVThe Shalimar Six?

WSYeah, because they were wearing Shalimar perfume—they were dressing up, wearing pearls and Shalimar, and giving really fun parties. And Harvard was so grim and depressing and political in my day, and apparently these girls really made everything fun. But our film is lower budget; there are only four girls, not six. If I’d done The Secaucus 7, it would have been The Secaucus 3.

CVHa! That’s good. Well, Martin Amis has this collection of essays with a fantastic title, The War against Cliché [2001]. And I would say that your screenplays are engaged in that same word-polemic. Is there anything that you do in your writing process to avoid falling into the habits of cliché? Are you conscious if you tap into something that you recognize as an also-ran turn of phrase?

WSYeah, it’s a terrible trap. Terrible. I mean, it’s sort of by accident that you develop a style or an approach and then are kind of trapped in that. My own career went awry because I didn’t follow the typical plan for indie filmmakers, I didn’t particularly want to write scripts; I just wanted to direct films like everyone else. I just wrote Metropolitan to have a script that I could direct cheaply. I’d already tried to write Barcelona [1994] as a script to direct. The thing to do, if you want a career in the film industry, is do your indie film, get it liked by someone, then follow it up by doing something that’s not personal. That’s key.

The “Gagosian & Film” supplement also includes: “Adaptability,” “Not Running, Just Going,” “Sofia Coppola: Archive,” “On Frederick Wiseman”, and “You Don’t Buy Poetry at the Airport: John Klacsmann and Raymond Foye”

Whit Stillman: Not So Long Ago (Fireflies Press, 2023)