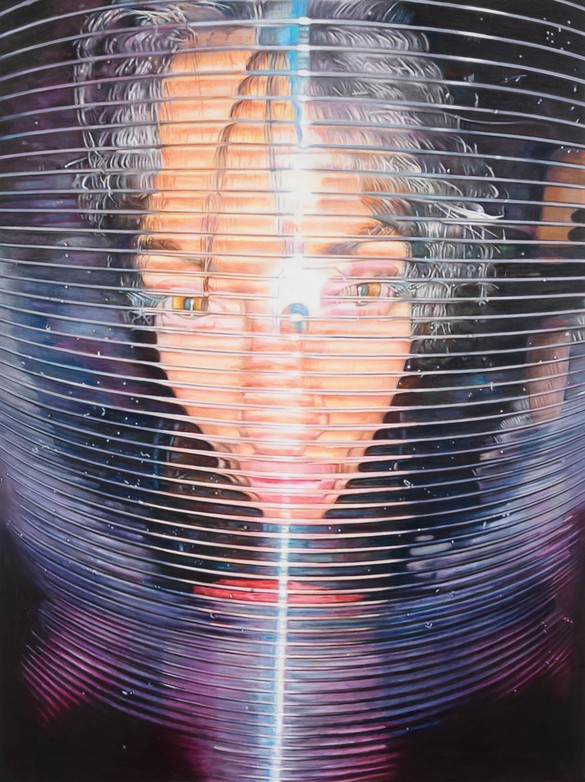

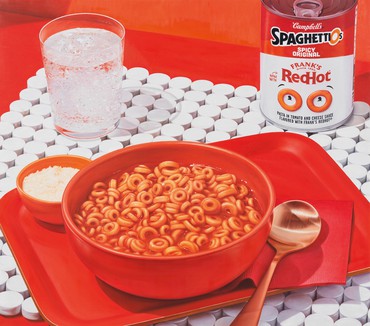

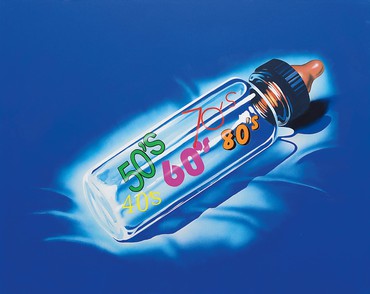

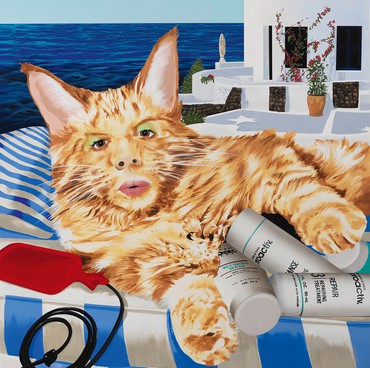

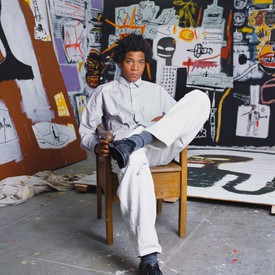

Jamian Juliano-Villani was born in 1987 in Newark, New Jersey, and now lives and works in New York. Composed using images borrowed from movies, memes, stock photography, art history, and printed matter, her airbrushed-acrylic canvases reflect the unpredictable pandemonium of everyday life. Her work is represented in American public collections including the Brooklyn Museum, New York, the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Jordan Wolfson was born in New York in 1980 and lives and works in Los Angeles. Filtering the languages of online and broadcast media through digital and mechanical technologies, and employing an array of invented characters, he crafts enigmatic narratives that explore uncomfortable social and existential topics. Photo: Collier Schorr

Jamian Juliano-VillaniThank you for doing this. I know you’re so busy, dude.

Jordan WolfsonI’m not. I’m just with my dad, and we’re on vacation together, so he’s by the pool. But let’s talk about your work. You sent me a Google Drive with a bunch of images from the last eight years.

JJVIt’s all over the place.

JWSo how has your art changed in that time? Are you working differently now?

JJVJesus. At first I did what I wanted. Then I gave the people what they wanted, and it’s back and forth for almost a decade now. Now I’m doing what I want again, and the paintings are happening as they need to.

JWYes, I’m the same. I remember in college I was doing the work I wanted to do; then I got out of school and I was doing the work I thought I should be doing to become successful. Then I hated myself and started making the work I wanted to again. Then I got nervous and for a second didn’t do the work at all. Now I’m back doing the work I want to do again.

JJVUltimately I have a responsibility to make paintings. I have a responsibility to myself and to the work. I view myself as an idea orphanage.

JWWhen you think about a painting, what do you think about? In terms of the total experience of what painting is, can you unpack that process for me? I know there’s content. I know there’s scale, there’s color, and there’s technique. How does it work for you?

JJVAt first I see an image, or a dream, and then I see a shape. The shape is usually formal. Usually one color. It functions as a TV screen at that point. You have the image or the formal “thing,” e.g., a piece of black construction paper or whatever. Then it needs to have some kind of vibration. Then after it has that vibration, you need to throw a stick in the mud. After that it needs to calm down, breathe, sweat a little bit. At that point I look at it—that’s where the reflection comes in—and then there’s the personal touch at the end. It’s like making a minimovie.

JWLet me break it down a little bit and tell me if I understand. First there’s this idea, or this image—I’m going to pretend I’m you. Don’t take offense, it’s not supposed to be a parody—

JJVI’ll roll with it.

JWSo there’s a hand reaching into a toilet. Then the toilet has teeth and eyes, and then the toilet is somehow floating on an image of the Maharishi or some type of enlightened person. Then there’s a watch on the wrist of the hand going in the toilet. Then the watch on the wrist has a certain time. Then maybe there’s potentially slime around the edges or something.

JJVI mean, kind of [laughter]. I told you I wouldn’t take it personally, but I’m like . . . Let me put it this way: there are so many different ways you can enter something that’s flat. For me, when I look at other people’s work, I want someone to force me into a direction. I want to be forced to be in that zone. It’s like being in a room with someone you don’t want to be in the room with. When I make paintings, I want to dictate someone’s reality for a moment, and then they can forget about it if they want. There are so many passive paintings, I can’t stand it. I started painting because I wasn’t seeing the paintings I wanted to see. I’m like, “You know what, I’m going to make them,” and I did. They evolved over time because I just kept on doing the things I liked. I put on horse blinders the whole time and just did what I wanted to do. Somehow that got me my very first show.

If anyone made those paintings now, that shit would totally not fly. Remember, I did this like fifteen years ago. Growing up in a silk-screen factory and coming from where I came from and seeing T-shirts being made—

JWI want to stop you right there. Basically you’re saying that you grew up in this very “high and low” environment; you grew up in “low” because your parents were producing merch for the Catholic church and all sorts of stuff. When you first looked at these “low” images that were being produced, what was your relationship to them as a kid or an adolescent? You saw a strangeness? Can you talk about that?

JJVNo, I never saw a strangeness in them at all. They just were always there, from day one. It’s like being born blind.

JWCheap, ugly, low, fast.

JJVNo, not low.

JWNo, but I mean low, like quickly produced.

JjvOh yes. Definitely quickly produced. I never realized how much my parents’ business would influence me. I tried to distance myself from it completely but I think it’s just in my blood. If you look at videos of my dad selling his merchandise for the pope, we’re like the same person.

JWAre those videos online?

JJVOh my God, I have to send them to you. You will die.

JWLet me ask you another question and then we’ll come back to this. What’s your relationship to scale in your paintings?

JJVIt’s so important. I started with things that I could actually lift and hold myself, because that’s what space allowed. I’m five feet two, and when I go up to a painting, I like to be trumped by it a little bit. I want it to function like a monument. It should look back.

JWDo you know Barnett Newman’s quote about scale? He says, “In the end, size doesn’t count, whether a painting is small or big is not the issue. It’s scale that counts. It’s human scale that counts. The only way you can achieve human scale is content.”

JJVYes, totally. That’s exactly what it is.

JWWhat’s your relationship to craft?

JJVI try to avoid it but it always gets in there. The problem is I’m incredibly specific when I paint. For me, painting has always been a means to an end, so I know every trick there is. I can tell when someone cheaps out, and when I say “cheap out,” I mean spiritually.

JWWho are the artists you worked for?

JJVI worked for Dana Schutz, Jules de Balincourt, Jessica Dickinson. I worked for the Leo Koenig gallery. I worked for Erik Parker, Marc Handelman. The list goes on.

JWOut of all those artists you worked for, who do you think was the most interesting?

JJVAll of them. Everyone has their own unique set of problems and you’re a broker for it, you’re the middleman. It’s like helping a beaver build its dam and every beaver does it different.

JWHow long does it take you to make a painting on average?

JJVHonestly, the shortest time for a painting that was successful, it’s probably two and a half hours. The longest one, six months. Like most artists, I’ve spent hundreds of hours on works that have never seen the light of day. I think it’s important to get these things out of your system. I usually like to do something last minute, too, to see if I still have it in me. I don’t understand these artists who are done at the opening, it blows my mind—I’m usually there blow-drying a painting dry. I always think, “This is the last goddamn time . . . ”

JWYes. I work past the opening, and for me—

JJVYes, dude, just lock the door. It’s my show. You know what I mean? People that are done on time, I’m like, “How lazy are you?”

JWI don’t think it’s really laziness, it’s just that—

JJVI know, but, like, push it. Let’s go. I wish a show could just keep moving, you know what I mean?

JWThough at a certain point, I don’t want to touch an artwork anymore. It gets to a—

JJVYes, there’s a shelf life on it, for sure. The second you’re like “Fuck it, I like it,” stop. Even if it doesn’t “look” finished, to me it is. Then it depends on the audience, like is the audience stupid or is the audience smart?

JWIt’s important to trust that the audience is always the smartest audience. You need to believe that the audience will understand you in an unconditional way, even though that might not be real or consistently true.

JJVThat’s the best way to make work. Yes, for sure.

JWWho’s the best artist in the past generation? Not your generation, the generation before you, or two generations back.

JJVMike Kelley. All my answers are everyone else’s answers, I’m sure. I’m not going to give you anything crazy. Robert Gober. It’s funny, my taste versus what I make looks so misaligned, but it’s not. Richard Artschwager.

JWDid you ever talk to Ashley Bickerton about your work? Did you guys ever talk about the things you made?

JJVI tried not to, because I was working with him as a gallerist [at O’Flaherty’s, the New York gallery that Juliano-Villani founded with Billy Grant and Ruby Zarsky]. I’m in a unique position with what I’m doing with the gallery; I try to keep my ego out of it because I want to learn from the artists. I’m hoarding information here. With every show I do with someone, I’m blown away because I learn something completely new. It’s like I’m gathering all these little merit badges of information.

JWWhat did you learn from Ashley?

JJVA lot. Passion and freedom. And how words really matter, how being present really matters. Also, I learned how to have emotional connections with other artists, instead of just looking at them as object-making people.

JWYou looked at an artist as a thing or an idea?

JJVIn a way—in any case not as a person. Then he made them personal, he made them people for me.

JWWhy are you committed to the practice of painting? Some of the artists you mention made paintings, but they had really expansive practices and are generally better-known for sculpture.

JJVI like the system of it. It’s self-contained in ways I am not.

JWCan you talk about that? If you’re an expansive-practice person, and at the same time you’re committed to the act of painting, why is that?

JJVObviously there are things that physically cannot be translated into painting—such as real movement, et cetera. There’s no way around it, and if the idea needs to go elsewhere, it will. The history and structure around painting gives me access to my intuition and something to parkour off of. Whatever vehicle translates my idea the fastest.

JWWould you classify making art as difficult?

JJVI don’t think it’s controllable; I think artists just do it. I think it really depends on your attitude, too.

JWDo you feel like people still have high standards for art? Or do you feel like standards have gone down?

JJVI think there’ll always be high standards for art. Success, however, means a variety of different things to different people.

JWWhat’s your version?

JjvSeeing something happen that hasn’t happened before.

JWI get that [laughter]. But I think your paintings function in a classical way. They’re at their best when they’re ambiguous. There’s a kind of release and a kind of restraint. How much do you look at contemporary image-making in entertainment, because a lot of these—

JJVHonestly, the most stressful thing in my life right now is that my Optimum cable isn’t working.

JWBut I’m thinking more about your use of brand iconography, like Marni, or Scott toilet paper. What’s the appeal of that?

JJVIt debases the painting, and the elegance of where I am. It’s a dose of reality.

JWWhy do you intuitively find that interesting? I think I’m a little older than you. It’s like your generation has a tendency to do it.

JJVWe’re consumers. It doesn’t have a reason in itself, but it’s part of what I’m trying to express.

JWIt’s interesting because if you look at the ’90s generation, they were affirming that cinema was a representation of the collective unconscious. Then Pop art was also related to the collective unconscious. But this feels different now, it’s not about a collective—

JJVNo, it’s about identity.

JWIdentifying as a type of consumer?

JJVYes. It’s like someone made that decision to get that specific thing instead of another thing.

JWLike, “Oh, I’m a health-food person. I’m drinking almond milk,” or “I’m—

JJVExactly. They’re signifiers. It’s about subjectivity.

JW“Oh, that type of person does that thing. Oh, this type of person has a TD Bank card. That type of person has a Bank of America card.”

JJVExactly.

JWI made an artwork years ago where I made an animation with Diet Coke bottles and I filled them with milk and they walked around the city. It was called Con Leche [2009]. I guess it’s a similar thing, but I wasn’t trying to talk about a specific person or identity. Diet Coke is a total-gestalt idea of a full type of social hollowness, or a type of—

JJVExactly. That’s what these are. For the same reason, there are so many things I won’t put in my paintings because they’re such low-hanging fruit—like flowers and cigarettes and liquor. I have a natural aversion to certain things.

JWWhat’s your relationship to or resistance to the paranoid censorship that’s going on today? Can you talk about that at all?

JJVI’m just ignoring all of that completely. Someone who’s been appropriating for years, someone who actually left their New York gallery because I was being censored—to think about that as something to even consider while making art is an abomination. The whole reason why we make art is because it doesn’t have to even be real. I’m more afraid of being dragged into a boring conversation about censorship because it really doesn’t make any sense to me.

JWHow did it feel to be censored?

JJVIt felt like I was being strangled. I started making art because it was what I wanted to do. Someone doesn’t have to like it, and I’ve said this so many times—you don’t have to like it, you don’t have to show it.

JWYou don’t have to look at it.

JJVYes, but you can’t tell me what I can and cannot make. I think art is the one last place where people are actually allowed to let their freak flag fly. If that’s taken away, it’s over.

JWI have to say I feel really good about my new piece Body Sculpture. I bring that up because there’s nothing I held back from the piece. Even if that alienates certain collectors or curators or critics or whomever else, I know that I stayed fully true to myself, and that’s more worthwhile, that has more value to me than any type of success. I can’t express how that feels to me, within my person and spiritually that I was just true, that I was true and I wasn’t fearless, but I moved through fear. I have a huge sense of relief in my conscience that I did that.

JJVYeah, I know, it’s a self-actualizing kind of stress. Learning to trust your instinct and accepting the reception of your ideas for better or worse.

JWI’ve had an internal fight to stay true to myself. I think what people and artists don’t realize is that even if you become a known artist and have a professional career, like you and I do, there’s a huge struggle to stay true, to stay legitimate, to the fundamentals of the practice, for whatever that means. When you see artists losing track, and you see artists decline in their work, it’s because they didn’t fight the good fight to survive, but if you’re constantly in that confrontation with yourself, it seems to be a path to a kind of self-legitimacy.

JJVI’ve been on all sides of this. It’s why I started the gallery, too. If I couldn’t make the work I needed to make, I wanted to facilitate others’ visions in the meantime.

JWI couldn’t do it, but at the same time, I believe the times change. I’m not opposed to changing with the times as long as I’m able to stay true to myself. I believe that all of us change. I believe all our work changes. I believe the authentic relationship to the audience requires it; the audience wants to witness us change.

JJV100 percent.

JWWhen I see another artist who’s still making the same work, it’s hard for me to be engaged with them any longer because I’ve changed.

JJVBecause you already know what to expect.

JWIf Stanley Kubrick made A Clockwork Orange [1971] or Barry Lyndon [1975] or 2001 [1968] over and over again, it would be boring, but every time he took on a new genre and he changed.

JJVYou want to see an artist respond.

JWWhat’s your relationship to male painters who emulate your work as a woman?

JJVI don’t identify with any of the aesthetics I use to make my work, they’re just a vehicle I’m using at the moment. If someone else can use them too, good for them.

JWWhat’s your relationship to commercial galleries?

JJVI like them. Sure they run on money, but they provide a few services for the public.

JWAre there particular galleries that you respect? Galleries that have an arc, or—

JJVAny fucking gallery I respect, dude. This job is fucking hard.

JW[Laughs.]

JJVLiterally, I respect all galleries because this shit is not easy. Artists have egos. It’s hard. At O’Flaherty’s, for one show I was unpacking cat-food cans out of a crate and I was thinking, “How the fuck am I going to sell this?!” And I really tried. That’s fucking crazy.

Jamian Juliano-Villani: It, Gagosian, 541 West 24th Street, New York, March 16–April 20, 2024

Artwork © Jamian Juliano-Villani