Cynthia Carr is the author of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, winner of a Lambda Literary Award and a finalist for the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize. Her previous books are Our Town: A Heartland Lynching, a Haunted Town, and the Hidden History of White America and On Edge: Performance at the End of the Twentieth Century. Photo: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

When not writing about books or art, Josh Zajdman is doom-scrolling Instagram or working on his novel.

Josh Zajdman2012’s Fire in the Belly was about the life, work, and activism of David Wojnarowicz. In March you published Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar. How did you decide on Candy as your next subject? Or, put another way, why Candy and why now?

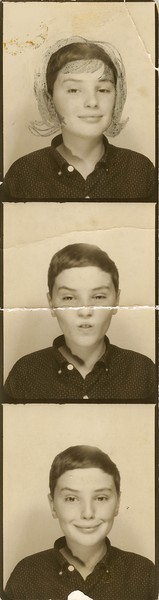

Cynthia CarrI worked on this book for ten years. It started in 2013, when Candy’s friend Jeremiah Newton and I both won Acker Awards, given to those keeping the boho spirit alive here in downtown New York. He won for his documentary Beautiful Darling and I won for my book on David Wojnarowicz. The next day Jeremiah called me and said, “I don’t know who you are but when I saw you onstage I decided you’re the one who should write a biography of Candy.” I wasn’t sure about that but I went to see him. He showed me some of her journals and letters and photos, but what really got my attention was a story that touched on her struggle. In Manhattan she was acclaimed, welcome at parties with the rich and famous, and so glamorous. Then, Jeremiah told me, she’d go home to Massapequa Park and her mother would say, “Don’t come till after dark. Don’t let anyone see you. Don’t answer the door.” And I thought, Now that’s a story I’d like to tell. When I write a book—and you know, it takes so much time and energy—I need to find an emotional connection, and there it was. I connected to the pathos.

JZJeremiah Newton is a constant figure in the book, and also a former biographer of Candy. What can you tell readers about him and their relationship to one another?

CCThey met when Jeremiah was still a teenager. He was a bit distrustful at first and she was a bit transactional—always looking for somewhere to stay, someone who could help her. Candy ended up living with Jeremiah in three different apartments, and of course she never paid any rent. He became someone she could always call on in an hour of need. He’d really do anything in his power for her. I think he regarded her as the most interesting person he’d ever known. She also got him into various inner sanctums. OK, not all of them—maybe she didn’t take him to the top parties—but he met many famous people through her. And she wanted to take him because he was handsome. She’d refer to him as “my husband.” I talked to Jeremiah about Candy for ten years. He died in November 2023. And I think he truly did love her. He was devoted to preserving her legacy, and after she died, in 1974, he decided to write her biography. He completed two chapters, one about Candy taking him to Warhol’s Factory for the first time and one about the out-of-town tryouts et cetera for the Tennessee Williams play she was in, Small Craft Warnings [1972]. I didn’t find them useful for my project but he did me an enormous service by interviewing over forty people who knew her and giving me the tapes. Most of those people were dead by the time I started: her mother, her father, friends she met in beauty school, the directors she worked with Off-Off-Broadway, and so on. Without his work I would have had no access to those crucial informants.

JZIt wasn’t just a matter of what she went on to become, but where she came from—a family of origin rife with shame, abuse, and repression. What was her relationship with them like, and did it evolve?

CCBy all accounts, Candy’s father, Jim Slattery, was quite charming until drunk, and he was often drunk, and then he was a brute. Candy couldn’t stand him, I think she feared him, but she never talked about him. She never said much about her childhood at all. Her mother divorced, then made the mistake of remarrying Slattery to provide Candy with a “masculine influence.” That didn’t last long. And he was out of the picture after the second divorce. Then he showed up at the hospital during Candy’s final illness, much to her dismay. When Jeremiah interviewed him after Candy’s death, Slattery claimed that he never even knew about her transition. And one of the astonishing, heartbreaking moments in my research came in that interview, when her father tells Jeremiah that he has no pictures of Candy except a couple from childhood, so Jeremiah then asks if he’d like some photos. And Slattery says, “No, I don’t think so.” His only child!

On the other hand, I think Candy’s mother really tried. She told Jeremiah that the first time she saw Candy in a dress, she decided, “I couldn’t hold my son back.” The mother, Theresa Slattery—usually called Terry—even got in touch with Dr. Harry Benjamin, an endocrinologist and early advocate for transgender people. In some notes that Terry wrote up about Candy’s transition, she also said that Candy had had hormone shots from “a famous doctor.” So possibly Benjamin. But I don’t think those appointments continued for too long. As for her saying “Don’t let anyone see you,” you have to remember that the Slatterys lived in a very conservative neighborhood and this was the 1950s. Homosexuality was illegal and transgender people were barely on anyone’s radar. Jeremiah talked to some of the neighbors after Candy’s death and heard that one of them thought “that kind of person” should be “put away.”

JZThroughout the book, you turn to Candy’s own writing, whether in diaries or letters, which served as a constant throughout her life. You write that “to go through her diary is to absorb a real sense of Candy’s isolation.” What kind of responsibility to Candy did you feel as a result?

CCI can’t write a biography without getting some sense of the person’s inner life. It can’t just be, they did this and then that and then that. I was so helped in my book about David Wojnarowicz because he kept amazing journals, and I don’t think I could have written about Candy without access to those feelings she told to no one except her journal pages. It’s part of getting to the person’s truth, which is the biggest responsibility I have.

JZCandy had an almost obsessive fascination with certain leading ladies of old Hollywood, such as Lana Turner, Kim Novak, and others. Why were those women touchstones for her?

CCA couple of things were going on. First, Candy made a study of beauty and femininity, so was there anything she could learn from the glamor and sex appeal of Lana Turner? But also Candy really identified with fragile, vulnerable stars like Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe. Near the end of her life, she described what she saw in Kim Novak to the journalist Julie Baumgold: “There was always something frozen about her. She had to squeeeeeeeze it all out. She was so scared, and that’s the way I was all my life. Everyone always told me I was beautiful but I felt frozen, just like Kim. There was always something wrong with her, something . . . slightly . . . unacceptable.” And Kim was her absolute favorite.

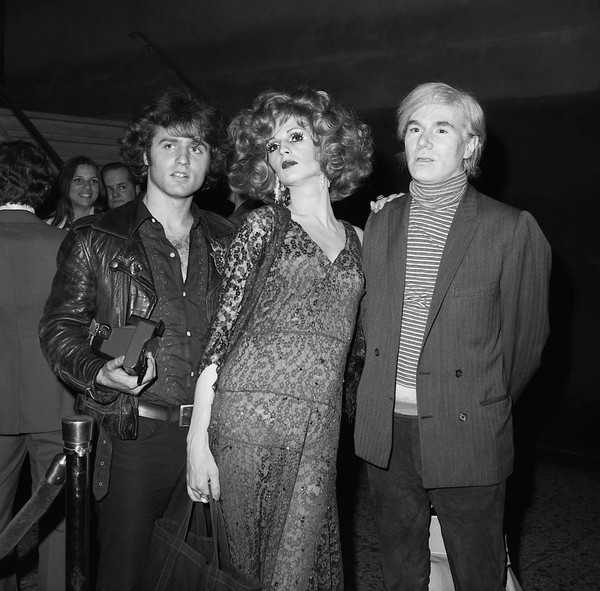

JZThough she’d go on to serve as muse to Richard Avedon and Robert Mapplethorpe, it’s Warhol that Candy is most closely associated with. What was their relationship like, and how did it endure?

CCI’m not sure she’d qualify as an actual muse to those two, but in general, photographers did love taking her picture. It was different with Warhol, who never photographed her. For starters, Warhol loved drag. He described her in Popism [1980] as one of the “true drags.” So yes, he thought of her as a drag queen. But then most people at that time, even friends, described her as either a transvestite or a drag queen. The actual term for Candy during her lifetime would have been “transsexual.” I found no evidence that she ever called herself that, and it doesn’t appear in her own writing about herself. What I did find in her journals was a wish for gender-affirming surgery, mentioned for the first time when she was seventeen.

But back to Warhol. Candy appeared in Flesh [1968] and Women in Revolt [1971], both often attributed to Warhol but actually directed by Paul Morrissey. And she seemed always to be welcome at the Factory—a fact not true for others I could name, like Jackie Curtis, who was needy and disruptive. Warhol developed a real affection for Candy and began taking her to parties and openings, movies and concerts. She was a perfect companion—witty, beautiful, and polite. And unlike so many others, she did not ask him for money. The result was that he occasionally gave her money, belying his reputation as a tightwad. Bob Colacello said that at the end of Candy’s life, when Warhol learned of her diagnosis, “For the first and only time in the seventeen years I knew him, I saw him cry.”

JZThroughout her life, Candy expected a big break, only to be sorely disappointed. One of these was in the now camp-classic film adaptation of Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckinridge [1970]. What happened?

CCVidal’s Myra is a beautiful trans woman obsessed with movies of the ’30s and ’40s. That described Candy to a “t” and she desperately wanted the role. Oddly enough, Jeremiah thought that she hadn’t read the book, but there was so much controversy and press coverage around it that she could have picked that much up by osmosis. The producers actually auditioned a number of drag queens and trans women but in the end the role went to Raquel Welch. Warhol thought it was a disappointment Candy never recovered from.

JZWhether the Summer of Love or Vietnam, Candy grew up against the constant immolation and rebuilding of American culture. You write, “Issues that preoccupied so many of her generation—Vietnam, civil rights, rock ’n’ roll—didn’t interest her. Nor did she ever assess her own situation as political. Candy was part of the counterculture by default. She never voted. . . . And Jeremiah felt certain she would have voted Republican if she’d had the chance. She did not oppose the war in Vietnam, for example. Yet, her very existence was radical.” How do you explain this startling asynchronicity?

CCShe grew up in a conservative family and she just never managed to question it. She didn’t seem to identify as part of a minority group; she identified as a woman, albeit one with a “flaw.” Was this her way of coping with her unusual life? Might she have changed if she’d lived longer? There’s no way to know. But remember there are transgender people across the political spectrum even now. I’m thinking of Caitlyn Jenner.

JZWhat was the significance of the word “flaw” for Candy?

CCThat’s the word she used for her penis. Candy completely identified as a woman but then there was this one little problem. As she once wrote in her journal, “I’ve got every limb and organ that a girl ought to have. Everything but one.”

JZCandy’s interest in comparative religion, spiritual practice, and self-help seems to presage fads of the ’90s through the present. What was she looking for?

CCCandy believed in God but she was raised Catholic, and that wasn’t going to work for her. Again she’s asking “How do I live this life,” and is there another faith that would help. In the book I track through a number of spiritual practices she tried, and they’re all metaphysical—meaning, they’re about controlling your body with your mind. Jeremiah told me that Candy thought she could will herself into becoming a woman. And that may be a glib assessment, but it’s no surprise to me that she ended up with Christian Science as the closest approximation of what she wanted—the problems in your body come from errant thinking, and so on. She lugged that Mary Baker Eddy book [Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, 1875] around with her for years. She underlined passages, copied some out, and wrote comments in the margins. In fact, this is where I found the only statement I could ever find about her thinking on gender. Eddy makes some comment about the two sexes and Candy writes—in pink ink—“Only 2? I believe more than 2 exist.”

JZIn a diary entry, Candy wrote, “I am not a genuine woman, but I am not interested in genuineness. I’m interested in the product of being a woman and how qualified I am. The product of the system is what is important. If the product fails, then the system is not good. What can I do to help me live in this life?” Can you illuminate her headspace in this instance?

CCI think she’s talking about her right to identify as a woman. One of the epigraphs to my book comes from Simone de Beauvoir, and it begins, “One is not born but rather becomes a woman.” And of course, given the time in which she lived—how could she live that life?

JZWas Candy homophobic?

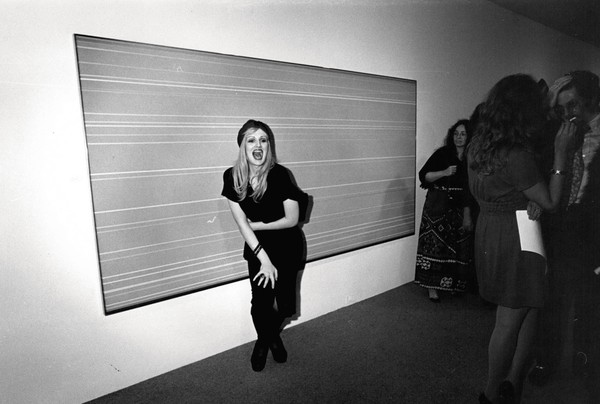

CCNo, but she could be thoughtless and mean. Most of her good friends and supporters were gay men. So OK—there were times when she’d get so angry at Jeremiah she’d start calling him “faggot.” That was meant to wound. Another tirade appeared in her journal one night after she’d finished her cabaret act at Le Jardin and in her own estimation had done a poor job: “Faggots are the most superficial things on the face of the earth.” She meant her audience, and that was the worst thing she could think of to call them. In Candy’s day the term “politically correct” hadn’t yet been invented. And maybe she wouldn’t have cared if it had been. It’s inexcusable, I know. But I see her that night filled with self-loathing and rage.

Note that when Candy first began venturing into Manhattan as a teenager, she usually dressed as a male. Drag was illegal and she hadn’t yet figured out how much she could risk. So then she was often identified as a lesbian. She was fine with that. It meant she’d been perceived as a woman.

JZThe biography is studded with marquee names whom Candy either met briefly or socialized with. I was surprised to learn about her closeness with Jane Fonda and, separately, Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner. Same goes for Lauren Hutton and Bette Midler. What did these women see in Candy that drew them to her?

CCI don’t think she knew Bette Midler very well but they were part of the same milieu—the Off-Off-Broadway world, where Candy was always accepted and respected. They would have seen each other at parties. She knew the others better, and all of them were kind to Candy. I don’t know that they were all drawn to her for the same reason, but I think she projected a combination of charisma and vulnerability. Lily Tomlin described it as “some ethereal light about her.” All of them tried to help her. Lily got Candy an audition at New York’s top cabaret, Upstairs at the Downstairs. Jane Fonda probably got her into that one scene in Klute—since I’m not sure how else she would have gotten in. Lauren Hutton was with Candy when she went into the hospital at the end, insisting that no, they could not put her into the men’s ward. And Jane Wagner did something very special for Candy. One of the more startling things I discovered in my research is that Candy lost ten of her teeth when she was eighteen years old. Paul Morrissey said he had to be careful about how he filmed her so the missing teeth didn’t show. They were all on one side. So Jane Wagner sent Candy to her own dentist—and paid for it. She finally had caps.

Candy met a few other notables who treated her like a freak. Groucho Marx, for example, chased her around a room trying to grab her penis. Despicable.

JZAnother formative if unexpected relationship was with Tennessee Williams. How did they meet and what did Williams think of her?

CCWilliams’s play Small Craft Warnings was struggling at the box office and the producers decided to bring Candy in as a kind of publicity stunt. When Candy showed up on her first day in the play, she went to the women’s dressing room, and the only other woman in the play, Helena Carroll, started screaming, “Get! it! out of here!” Tennessee himself went to the men’s dressing room to ask if Candy could come in with them. No. She ended up in a prop room or broom closet by herself. There was only one actor in the cast who would even speak to her when they weren’t onstage.

Tennessee was horrified by this. He’d sit with Candy in her closet sometimes and occasionally took her out to dinner after the show. He thought she was “marvelous to work with” and played her part extremely well.

JZShe wasn’t always Candy Darling. What were other names she went by initially?

CCFriends of Candy’s who were there as she began to transition remember her considering “Kim” and “Hope” and “Star” and “Candy,” plus other names they couldn’t remember. She actually had a Social Security Card in the name “Hope C. Slattery”—C for Candace, of course. She used that when she had some short-lived office jobs in the mid-1960s. She wasn’t “Darling” at first. She went by Candy Cane and then Candy Dahl and maybe Hope Dahl. Then her friend Taffy Titz called her “Darling” so often that it stuck.

Cynthia Carr, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024)