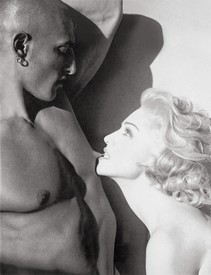

Arinze Ifeakandu is the author of God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, which received the 2023 Dylan Thomas Prize, the Story Prize Spotlight Award, and the 2022 Republic of Consciousness Prize, and was a finalist for the 2022 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction, the Kirkus Prize, and the CLMP Firecracker Award for Fiction. Photo: Bec Stupak Diop

I was playing Frisbee on the football field when Soludo finished from his meeting with the principal. It was nothing bad, he was not in trouble or anything like that—sometimes our principal, Sir Mellitus Obinweke, liked to sit on his lawn with the cricket players, at other times with the choristers, drinking malt, eating chin chin, and talking things. That evening it was the turn of the cricketers. I tried to dodge, to hide from him, but already his eyes caught my eyes and he’d done his face like so: eyes narrowed into thin, knowing slits, as though reading my mind and saying, I dare you. I enjoyed spending time with Soludo. It was my second month there, at Marian Boys’ Boarding School, and I could say with my full chest that he was probably my closest friend. But I knew what he wanted today. I had been promising to tell him some more stories; now, he had that look on his face that said No more excuses—but I was not in the mood, it was Free Time, the two hours before supper and night prep when we could be wherever we wanted and do whatever we pleased.

That evening I chose to play Frisbee with my classmates. I was the goalkeeper, standing in front of the net, watching my friends like a hawk as they chased one another in the half-field, the other half occupied by some JSS 2 students (Soludo’s classmates) playing set. They ran and ran in circles in their blue day wear, my classmates, laughing, dodging their opponents, flinging the yellow ice cream–plate cover into the air and then chasing it as it curved and curved in the breeze, catching it midair, dodging some more, while each team tried to find the perfect moment to curve the Frisbee at me, aiming to get it in the net.

I stood at the center of the net, alert as my friend Samson had once shown me, ready to dive in either direction. I felt light as a breeze whenever I did this, sometimes catching the Frisbee midair, causing a groan from one team and cheers from another. I liked to fall on the prickly grass, nursing my catch, like a goalie who had saved a risky shot, but sometimes I surprised them by throwing back the Frisbee immediately, as high and as far as I could, watching it curve and curve in the air, watching them run in circles, arms outstretched.

Soludo was walking with two boys, and because my classmates were still chasing each other around, throwing the Frisbee from one team member to another, I turned briefly, holding the net like a prisoner behind bars, and made a reluctant face, frowning, pouting my lips. Soludo smiled and shook his head, like he could not believe this boy. His friends Collins and Kachi split as they got closer to the field, Kachi headed onward toward his dormitory, Awka House, Collins headed to the Dining to see whether the cooks were done with supper—he was assistant bell ringer, the only senior in SS 1 among the now separated trio. Soon he would be scrapping and banging an iron rod against the rusty rim of an old tire—the handbell was for Classroom Block only, not the dormitories—the metallic tune going “Marian Boys, Marian Boys, come and eat, eat, eat!” Soludo pointed his V fingers at his eyes, then at me, like, I see you, before jumping onto the corridor and disappearing into the dark mouth of Waddington House.

I turned around, returning to our game, and there it was: a wave of blue tumbling my way. The Frisbee spiraled toward me, fast and beautiful. “Watch!” someone yelled, and before you could say Jack Robinson, the ice cream–plate cover was in the net.

“Goal!!!” they shouted, four, five boys high-fiving each other, another five grumbling and looking pissed at me: “You weren’t looking!”

“Sorry, sorry,” I said, picking up the Frisbee.

My friend Samson was on the losing team, and his face was squeezed in anger. Samson hated to lose. “No, replay,” he said, walking to the other team. “Ifeanyi wasn’t looking.”

“Our luck,” said Osita, the leader of the other team, approaching Samson. Osita was lanky and light skinned, looking not like a fighter at all, with the faintest sprinkle of black hair on his upper lip, where he told us his mustache would be growing soon. When he walked, it was as if he had neither time nor energy for anything or anybody, his long arms swinging, his torso tilted slightly backward and sideways, like a tree vaguely askew.

“That’s not fair.” Samson was turning to his team members, turning to the other team, looking for supporters. His lips were pursed, making his face appear ratlike—this is not to say that he looked like a rat, no, he simply had a thin, scowling face, and whenever he put on his fighting look, well, that was when he appeared ratlike. He was wearing a darker shade of blue—his parents, like some others and unlike mine (who had simply followed the rules laid down in the admissions bulletin), had sewn a pair of day wear instead of buying from the school’s tailors, which made sense, they fit him perfectly, unlike mine, which were closer to sky blue and a little oversized. In our second week at the school, Sir Mellitus Obinweke had ordered the prefects to fish out everyone wearing the wrong shade of blue and Uncle Maths had given them each six strokes of the cane on the buttocks, in front of all the boys gathered outside Awka House for the impromptu assembly that afternoon.

“Would you say the same thing had you been the ones that scored?” Osita queried. Both teams were now in a face-off and I was walking toward them, ready to mediate, to say, My fault, my fault. The sky was ashy blue, the air cool, which meant maybe it would rain later that night. (“Watch the clouds, the way they move,” Soludo had once said, though there were really no clouds today, only the ashen sky and a soft gentle breeze.) Everyone was now talking all at once, speaking rapid Igbo, making hunger pass through my stomach and my head, like I might collapse; I couldn’t stand them fighting in Igbo, it made me somewhat afraid of them, like they were more grown-up than me. Only adults quarreled in Igbo where I came from, which was Sabon Gari, Kano. We, the children, fought in pidgin, saying things like, Your father left yansh like burnt bread!

“This is all your fault,” Samson said, turning to me. “Why weren’t you looking?”

“It was a mistake, sorry,” I said, in English. “Why don’t we keep playing? I will give Samson’s team one allowance.”

“No,” Samson said. “We will cancel this goal, count it as an offside.”

Osita smirked, amused, looking from person to person, as though to confirm that he alone was not hearing that ridiculous proposition. “Please repeat yourself.”

“We would have to count this as an offside.”

I held the Frisbee behind my back, ready to run—soon they’d be fighting over it. Samson and Osita stood in front of each other as though they were about to kiss, but those angry eyes told a different story, Osita glaring down at Samson, looking all smug and ready, Samson glowering up at him, making me think of David and Goliath: one small boy against a mountain man. I didn’t see Osita as a mountain, though, he was more of a wiry tree, and I imagined his long-long hands stretching out to slap Samson stupid. There would be no space for Samson to slap back—we’d all seen Osita fight before and it had been a whir of hands on the other boy’s face. Not a fair fight at all. Glancing toward the Staff Quarters, which were to the right of the Classroom Blocks, we noticed that the parking space bordering the Staff Quarters and the Executive Block was empty; usually two cars were parked there, Uncle Art’s gray Peugeot and Uncle Maths’s red Mercedes-Benz, old cars spelling trouble. Earlier we’d seen Chaplain drive out, his silver sedan, the only new car in the entire school (except from when a parent visited, then the tiny lawn by the Staff Quarters would feature a shiny new car), going vroom, all speed. Chaplain often drove fast, blowing his horn right from the Executive Quarters, where he lived with his wife in the flat below the principal’s, turning slowly into the long driveway bordered by Ixora and salamander hedges and accelerating near the pine trees by Classroom Block that bowed when it rained, like saints at worship. When he drove off earlier, we’d waved, chanting, Chaplain, Chaplain, and then we’d rejoiced, feeling free.

Now I wished his car were there, any car at all, something to spell trouble, something I could point at and say, Think twice. I hated being in fights, and though I was not the one about to start tussling in the grass, I was in the middle of it, my name would be called when the trouble exploded and scattered everywhere. My other classmate Ejiofor, whom we sometimes call OBJ, because he looked like the president, Obasanjo, with his big stomach and fat cheeks and long pursed lips—he stood between them, saying “Hey, hey!” He was spreading his arms and legs, one hand facing Samson, the other Osita, and—because they kept approaching—putting two fingers in his mouth and declaring a foul with the whistle of his mouth, like a referee. Two shrill whistles, piiim, piiim. “Stop this nonsense!” he said, almost screaming, like they were about to punch him.

Samson turned to me. “Give me the Frisbee,” he said, scowling. “We’ll cancel the goal but settle this with penalty throws.”

“What?” Osita almost died laughing. “Unu a-na a-fukwa this boy? You must think you’re the boss around here.”

“That is what we will do,” Samson said, hand outstretched. “Give me the Frisbee, Ifeanyi.”

Osita was rushing to grab it from me, the both of them were. I ran—back toward the net, then zigzagging away from it, like I was about to cross our half of field into the other half, where one of Soludo’s classmates was dribbling a football. They were hot on my back, both boys chasing, the other boys joining them, Samson saying, Ifeanyi, Ifeanyi, like he would fight me if I didn’t stop, the other boys saying, Ifeanyi, Ifeanyi, with laughter in their voices. When I got to the white line demarcating the field, I stepped on the circle of the midfield, then, turning back to face Samson and the boys, flung the ice cream plate high to my right, where Ejiofor was waiting, and it sailed and sailed in the air, and I watched two crows flying leisurely across the turquoise sky, and then the other boys rushing toward the Frisbee, arms outstretched.

Ejiofor caught it. “Kenneth!” he called, flinging it at a boy in Samson’s team (Ejiofor was in Osita’s), and it became clear to me that this had turned from a simple game of Frisbee to a game of catch, and that Samson and Osita were “it,” the ones to run around in the middle of the wide circle our friends had now formed, trying to catch the Frisbee. And with this new game, nobody had time to keep scores: you were simply “it,” or you were not.

I was not happy with Ifeanyi, but I went, after lights-out, to Soludo’s corner to hear him tell his story. He titled this one “A Bird’s View of Everything.” I had no idea where he got his titles. One story he told often was called “The Night the Minstrels Came,” and another one was “What Happens When We Go to Sleep?” It was my favorite, it reminded me of Nko’s style, with talking animals and benign and malignant spirits. Ifeanyi had admitted that he modeled the story after one of Nko’s, “Njakili,” a story set in the evil forest of Nko’s iku nne—before the missionaries came and broke the land, as Nko put it.

His newest story, “A Bird’s View of Everything,” was about Prosperity, the ghost that sometimes sang in the toilets of Block B, or so he said. She was often bent over a bucket, washing and washing, whistling nonstop. On those nights when she did her rounds, nobody dared approach the toilet after lights-out, the sound coming out of that place was eerie and frightening, alternating between the dry cackle of an old demented woman and the warm, syrupy voice of a child. She laughed and sang all night long: sad, languid songs; mocking laughter. We did dare to approach the doors, tumbling out of our dormitories and standing at the entrance, and we saw her hunched-over shadow, her pointing chuku like the head of Medusa. She often washed as she sang, we could tell from the motion of her hands, the hands of her shadows on the wall. She would throw her head back and then her shadow would be gone. We fled then, rushing into our bunk beds and those of our friends, hearts pounding with fright and excitement. Sometimes she paced around, her shadow crawling on the walls like a giant spider, climbing, climbing. But the silence after her song was like a grace bestowed—she sang until 4am, when we’d done our business elsewhere and, tired out, were sound asleep, breeze blowing in through the many open windows, I in Nko’s bed, his legs draped over mine. Nko slept like it was wartime somewhere there in his dreamworld, turning and turning, holding you, letting you go.

Now, Ifeanyi told Soludo, Bobby, and me that he’d dreamed of Prosperity. He knew it was going to happen when he read the poem on the wall of Block B’s stairwell that night, the new poem everyone was talking of that week, about the Opam’s pallbearers. We didn’t know who wrote those poems. In the dream he stood on Milking Hill, watching a war unfold. He had a sense of déjà vu, like he had been there before, but many centuries ago—everything below was strange yet familiar. It was the same rolling green hills and the same red-brown earth, but in this previous life before the dream the landscape was dense, thicker with tenuous trees. From his perch on the hill, he could only see the clustering head of the forest, a few clearings scattered in-between, from which the smoke of daily life billowed. There was a village down there and it was peaceful. Drums sounded in the distance, birds rising and fluttering, hawks gliding, everything as it should be—their beautiful flight, the syncopated sound of the lives below.

That was in an earlier life. The vegetation of the dream was thinner, littered with aluminum-roof bungalows and red-clay huts, their roofs thatched. He was on that hill for days, watchfully waiting, he felt a responsibility to tarry, to accompany—for what reason he could not tell, except that the nights were heavy with the weight of things to come; he noticed movements in the bushes at night, car headlights flashing timidly on their hurried errand from house to house. Secret flights, he thought. There was peace below in the village otherwise, or a semblance of normalcy: children walked to the stream at the foot of the hill in the mornings, and then to school with their slates, singing all the way, and women cooked at their hearths, and goats and chickens milled around, pecking at the ground.

He began to feel like a bird caught in the rain, wings laden with premonition.

It was as sudden as my confusion: my desire to fly. I had been a bird all along and did not know it. What kind of bird? you ask. I cannot say exactly. On some days I felt like a sparrow joyriding above the clouds, at other times I was a hovering hawk. I was never a crow, though—and yet crows were all I saw there. All the regular birds were gone, the sky empty of pigeons and colorful swi-swi birds. At evening, crows congregated on the branches of the great oak tree under which I sometimes sat, covering every inch of it, looking eerie in their clustering, having made the greens disappear so that the tree was in tatters of blackness. Their cawing was like a million voices prattling in my head, like a hundred conversations going on at the same time, as though my mind were a great meeting hall of everyone everywhere.

At that time, I’d been on Milking Hill for seven days. You know how time expands in a dream, how elastic everything becomes, so that a century’s event is packed into five short-lived minutes? How a mere twenty frightening seconds of a nightmare can seem to last forever? Exactly. I felt the complete exhaustion of my long, idle wait, and something in me said Fly, so I spread my wings, which I did not even know I had, and did just that, fly. I can’t describe the sensation except that it’s pure rapture. First, the ticklish feeling in your sides, like you’re in love with danger itself. You feel heavy, like you might plummet, and if you look down, you see clearly the lay of the land, the pixelated outlines of trees and houses, depending on how high you go. After that, you feel light as air, trusting that the wind, no matter how weak, will carry you safely. I flew far and wide, traversing the sky from Coal City to Udi, perching on palm trees in Nsukka, where I saw the carnage that had begun brewing, fumes clogging the sky, and the rat-tat-tat of gunfire. My entire body was seized by convulsions of remembrance—I’d been there before. I fluttered from a mango tree across a row of pretty bungalows onto the roof of one of the houses. It was a ghost town down there, the deserted streets littered with evidences of forced exodus (I knew this instinctively and did not question my knowledge, which felt timeless and deeply etched in my tiny bird brain), wheelbarrows and jerrycans abandoned in the middle of streets, charred cars with their doors flung wide open. When I landed on one, I felt deeply the terror of its long-gone occupants, smoldering, their sorrow burned my talons; saw clearly a vision of their last moments, hostile soldiers dragging father and mother and children out of their blue Mercedes. Wawa, said one of the soldiers, in his thick Northern accent, headbutting the father with his gun. He cackled, standing over the man who, paralyzed by terror, was struggling to stand on his feet. The man had a gentle Igbo face, like my uncle Okey, with his thick sideburns. The Colonel put his feet on the man’s chest, booting him back down, forcing him to his knees. He began to undo his belt. The other soldiers stood there, sniggering and shaking their heads, which meant he had done this before. His penis was like a snake, a long black cobra, his piss like smelly green venom all over the man’s face. His wife was holding their two kids, who seemed somewhere between ten and eleven years-old, burying their faces in her bosom, shielding them from their father’s humiliation. She shut her eyes, too, looking away. The Colonel halted his pee, commanding his men, who gripped the woman’s shoulder, prying her from her children—their wailing, too heart-wrenching, little girl crying Daddy, little boy crying Mummy, woman weeping—making them watch.

Nyamiri! The Colonel barked, mean and fearsome. Open your mouth.

The cries and screams ringing across town were as hollow that cavernous morning as they had been centuries before, when a neighboring town attacked before dawn, with their ten-man cavalry and infantry of thirty, torching people’s huts, slaying the men who, surprised out of sleep, came out with their spears and machetes, their bows and arrows. Humans, when confronted with terror as unimaginable as this, scream all the way to the other side, their wailing ringing with grief and unbelief, baffled denial to the very bitter end: it could not be true that the world had picked them for such senseless violence, such heartbreaking end. No person, hero or villain, has ever sat still in the face of such devastation.

I fluttered away.

“You haven’t told us how you saw Prosperity,” I said. I enjoyed listening to Ifeanyi’s stories, but unlike Nko, he tended to digress a lot, which wasn’t entirely bad, because everything he said he made super clear and entertaining, especially the way he demonstrated, crouching up on his knees in Soludo’s bed earlier as he described, in animated whispers, his first dream flight, flapping his wing arms and then sailing his cupped palm through the air, showing us how the sparrow traveled.

“Be patient,” Bobby said, glancing at Soludo, as if he expected a cookie from him for speaking up. “He’ll get there.”

Soludo nodded, absent-minded, smug as always.

“Prosperity is the little girl,” Ifeanyi said.

“How do you know this?”

“Because she told me. She did not tell me-tell me but following her I kept hearing the poem in my head: The pallbearers from Opam’s arrive / In their shapeless shoes. It was like a chorus in my head: Hoisting your casket. / Step to the left, step to the right— / One, two, three, they go, / Shoulders stooped with the weight of you.”

It was chilling, the way Ifeanyi recited the poem, deadpan, slow, his eyes eerily reflecting the moonlight. His voice cracked halfway through, as though something were caught in his throat. Deadpan shifted to fire, his voice and eyes animated, a coldness descending in Soludo’s corner by the dormitory’s wide, wide windows. We all lay there on our stomachs, Soludo, Bobby, Osita, and me, silent as night. He was backing the window, Ifeanyi, and the corridor’s lights illuminated him vaguely, aglow behind him, shadowing his face. It was an uncanny transfiguration, this was the Ifeanyi we all knew, harmless, the scarediest cat in our class, with his gentle voice and Nwa-Mummy face, now looking momentarily fearsome. That was exactly how incantations worked, exactly how people fell into trances: the poem injecting its essence into the cantor’s soul, bringing him close to divinity.

My late great-grandfather Ichie Obejeri had been a powerful dibia in his lifetime. My mother used to tell us stories about him, that he could create and dispel rain, calling forth thunderstorms to disrupt the gatherings of his enemies, holding the rain for his clients so that the sky grumbled all day long but dared not weep until the end of the event. He lived to be 112, and I sometimes imagined him with my eyes closed, hearing his quivering voice in the darkness of my mind, how he would go from tender to crazily otherworldly, all because of a few poetic words said over and over, how he would dance in circles for hours, rattling his metallic ofor. That was the sort of thing I believed Ifeanyi was playing with. Nobody knew how the poem had found itself in the stairwell of Block B, for all we knew it might have been inscribed there by the hands of an evil ghost, and there was Ifeanyi casually reciting its incantations, making himself a willing vessel.

“Six feet into the ground you go,” he said, completing the poem after a short pause, his go coming out like he was saying boo.

“Jesus, Ifeanyi,” I said. “Be very careful with this story.”

Soludo snapped at me. “Bia this boy, you can leave if the story is too much for you. Ifukwa? Don’t be disturbing somebody.”

I followed her scent, the little girl. Hers was the only one containing pungency, which I came to understand was the universal scent of life. It is a musk, each person’s unique, some containing more odor than sweetness (and vice versa), depending on how much atrocities you accumulate, the Idi Amins of this world oozing—as their essence passes our nostrils—pure bile. Remember what Uncle Social Studies told us about him, that he refrigerated the flesh of the people he murdered? I perceived that stench on the Colonel, too, and wherever he went the scent of the girl went with him, though I could not see her, not even when I perched in the soldiers’ camp, hopping from tent to tent. I was invisible to them but they felt my presence, it seemed, because they always looked directly at me, puzzlement scattered all over their faces, at first it startled me right out, their piercing gaze; but it was my dream, a good dream in spite of its painful contents, and I knew I was safe.

The soldiers rolled their armored tanks through towns and villages, shooting down everything in their path. They stayed in the compounds they sacked, making small campfires over which they roasted their spoil, goats bleating plaintively, even they were not spared the soldiers’ cruelty, made to run like prey around a circle of hooting soldiers. It negated everything I knew about Muslims and their treatment of animals—slice the ram’s throat, one clean cut, make it quick, show mercy. Perhaps that was the injunction for Salah alone, you never know with humans, their partial rules created to entrench hierarchies, to allow exactly this: coldhearted men who, in order to forget the fact of their nothingness, must make a sport of death.

Text © Arinze Ifeakandu 2024