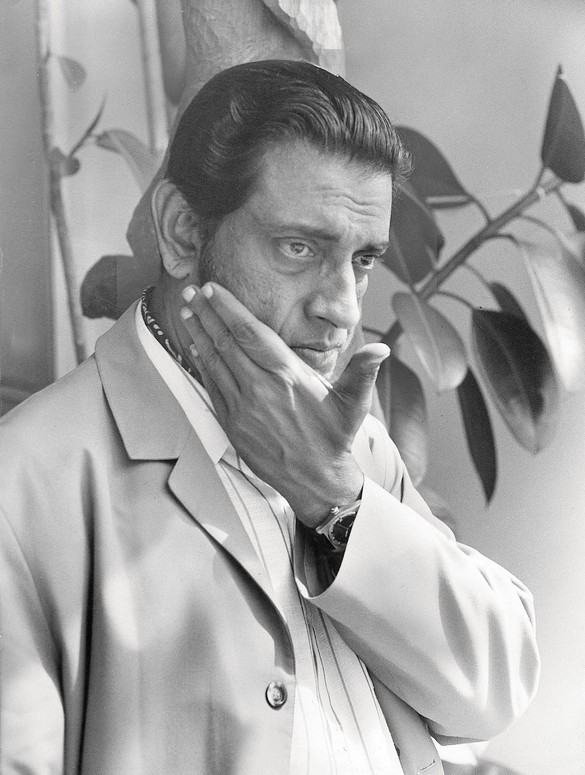

Amit Chaudhuri is the author of eight novels, the latest of which is Sojourn (2022). He is also a poet, essayist, short-story writer, and musician. His New and Selected Poems is scheduled to be published in 2023 in the NYRB Poets series. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and edits literaryactivism.com.

Where does Satyajit Ray come from? Not the filmmaker, whom we know came from India, from Bengal, but the practice we associate with him? Was he a one-off, as he’s sometimes assumed to be? There have been recent occasions for us to think about these questions, most notably, in 2021, the centennial of Ray’s birth. New books of previously unpublished material have also appeared, including Satyajit Ray Miscellany: On Life, Cinema, People and Much More (notes, brief essays, interviews, even LP sleeve notes), put together by his son, Sandip. But the questions these publications raise remain largely unattended to. For now, it seems that the endorsement of the filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan, a gifted follower of the director’s, on the jacket of the Miscellany must suffice: Ray is “a most singular symbol of what is best and most revered in India in cinema.”

Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (1955), an anomaly in Indian filmmaking at the time, immediately placed him in the burgeoning art-house movement—a movement Ray was both sympathetic to and somewhat ambivalent about. But he was an Indian, so the recognition he received at Cannes in 1956 was not for best film but came in the form of the festival’s inaugural Best Human Document award, as if films about India, and Indian villages especially, had to be appreciated primarily in terms of the empathy they demonstrated and only secondarily as cinema. The word “human” stuck, and Ray began to be called a “humanist,” whatever that means in terms of an artist’s contribution. Ray went along with the label from politeness. In an interview with his biographer Andrew Robinson, however (included in the 2021 edition of Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye), Ray, asked “Would you ever call yourself a humanist?,” replies, “Not really. . . . I am not conscious of being a humanist. It’s simply that I am interested in human beings. . . . I’m slightly irritated [laughs] by this constant reference to humanism in my work—I feel that there are other elements also. It’s not just about human beings. [My emphasis.] It’s also a structure, a form, a rhythm, a face, a temple, a feeling for light and shade, composition, and a way of telling a story.” A “rhythm . . . a temple . . . light and shade, composition”: these are Ray’s words for the “other elements” and histories that direct artistic concerns unaddressable by realism.

Ray’s work (“a rhythm, a face, a temple”), like his angularity to humanism, is the product of a shift in thinking in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that’s connected to the emergence of certain practices in the arts. This shift reshapes the world quite differently from the way in which the Enlightenment or imperialism do. For one thing, it’s hardly unidirectional, moving from West to East. And it represents a counter to the human-centered Enlightenment. Its occurrence means we can take few of the terms we fall back on when accounting for our modernity as givens. Ray, and the aesthetic that roughly the first twenty-four years of his work explores (right up to the release of the children’s film Joi Baba Felunath in 1979), should be situated in, and understood as, a radical reexamination of these givens.

The eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries were a time of extreme change: this much we know. The conventional narrative emphasizes traumatic dislocation, the consequence, evidently, of religion receding and Western society breaking down. The postcolonial narrative describes the traumatic effect of imperialism in Asia and Africa. The obverse of these narratives, equally well-worn, celebrates the period’s advances in political thought, social reform, technology, and industrialization.

To me it seems that the radical cultural change of the last three centuries is impossible to grasp outside the inspiration created by a transformative convergence between cultural and artistic lineages that took place in that period worldwide. We are all, in one way or another, an expression of this convergence. And the history of the convergence frees us from viewing the past through the narrative of breakdown (in the West) or repression (in the rest of the world); it allows us to grasp why our experience of much of what we know of the last three centuries is liberatory and revivifying, but in a way quite unconnected to our reverence toward the miracles of “progress.”

To say that this convergence merely comprised the meeting of “East” and “West,” or of Europe and the rest of the world, is lazy. These separations become increasingly difficult to make. After all, something like the Enlightenment view of the human being’s place in the world is establishing itself everywhere by the eighteenth century: through contact, new mercantile opportunities are creating new ambitions, new educations, and new colonial pedagogies. By “colonial pedagogy” I mean not only the use of knowledge and education as an instrument of power in various parts of the Empire, I also mean their use in Europe as disciplinary and disciplining tools to homogenize Europeans and their pasts. In this sense there isn’t that much difference between colonial pedagogy and pedagogy itself. In the midst of this, the intercultural shifts that begin to happen at this time create, gradually, an alternative pedagogy that might be called poetry, or, later, modernism. It involves the fragmenting of various Renaissance types of monumentalism, among which “the real” may be the biggest monument of all.

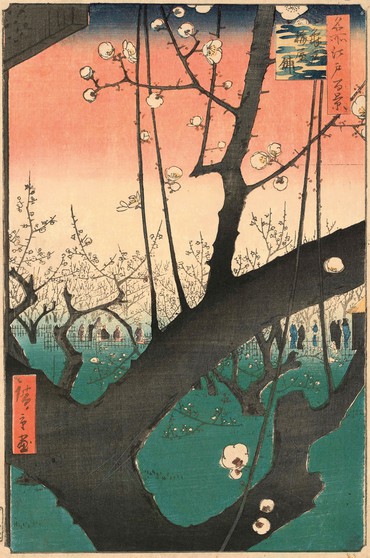

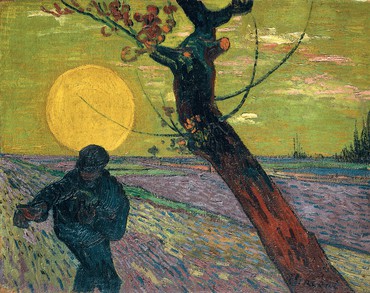

So, in opposition to the oil paintings of the late Renaissance, and the works of neoclassical sculpture that seek or achieve the quality of the monument, arise the frayed aesthetics of Impressionism, nonrealistic modernist figuration, and the sparse, clean lines of the Bauhaus. In opposition to the realist novel arise modernism and the idea of poetry that Roland Barthes identifies as a condition of language no longer dependent on markers such as rhyme or ornamentation. It’s impossible to understand these changes without the cultural encounters that begin to open up escape routes, escape routes made possible after writers, critics, and artists come into contact with, for instance, the Upanishads, the Gita, Buddhist notions of “reality” (without which Ezra Pound could not have compared experience to iron filings on a mirror), the “African mask,” Chinese poetry, and the Japanese print. Some or all of these and more were studied closely by Barthes, Pound, Matthew Arnold, William Blake, John Cage, T. S. Eliot, Vasily Kandinsky, D. H. Lawrence, Agnes Martin, Henri Matisse, Friedrich Nietzsche, Pablo Picasso, Arthur Schopenhauer, Vincent van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, William Wordsworth, and others, eventually allowing them to position the arts, and thought, as contra-Enlightenment practices. This is why, when we look at the transformation that the arts represent in this period, we feel not panic (as we would if fragmentation simply represented breakdown), or improved (as we would if change comprised only development): we feel energized and delighted.

The delight is connected to two things: to being offered an alternative to the Enlightenment’s masterful relationship to the world; and to the nature of the world-affirming, defamiliarizing provenances (the “African mask,” a raga, the Upanishads, a mid-nineteenth-century Japanese print) of some of modernity’s most liberating projects (Wordsworth’s The Prelude [1850], Woolf’s To the Lighthouse [1927], the paintings of Matisse, the songs of Rabindranath Tagore, the aleatoric compositions of Cage). The unprecedented cross-cultural give-and-take from Romanticism onward, and the alluring problem of creative practice since then, remind us that modernity is not only a time of disenchantment or of progress, it’s also a time of liberation from the habitual constraints of consciousness. This—rather than technology—is what enlivens us about modernity.

One of the most important bits of this story is largely unknown, or insufficiently discussed; or our knowledge of it, despite new scholarly work, is, ironically, decreasing in our globalizing world. The fact that Picasso took a cue from the “African mask” is familiar to droves of museumgoers today (though Picasso downplayed his indebtedness later in life). But what might a Senegalese contemporary of Picasso, or the descendant of that contemporary, have made of that mask? What, for that matter, did they make of Picasso? I refer not to the question of cultural appropriation or ownership but to the matter of creative reuse, which turns all creativity, whether it’s taking place in Central or West Africa, in Spain or Paris, in Kolkata or Tehran, into a form of appropriation and renewal, located in, and actively contributing to, history and historical change. The twentieth-century Senegalese modernist is in a situation, then, of significant complexity and excitement, a situation encompassing the mask, Africa, and Paris in a way that’s similar to, and emerges from, but is also different from, the situation of Picasso.

Picasso turned to the mask because he felt that neoclassicism and Renaissance realism were dead. As a boy and a trainee, he had devoted himself to mastering their idiom; the result is The First Communion, a lucid scene in oil from 1896, when he was fifteen years old. To the post-Trocadéro, post-1907 moments belongs the decisive movement away from representational traditions, as well as such provocations as “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.” The sentence contains both a personal and a cultural history. “Child,” “primitive”: these are code words for a nonrepresentational art of extraordinary sophistication. In Art, published seven years after Picasso’s visit to the Trocadéro, the critic Clive Bell (an almost exact contemporary of Picasso’s) decried the overwhelming body of representational art that had become synonymous with the Western tradition, calling it, somewhat derisively, “Descriptive Painting”: “We are all familiar with pictures that interest us and excite our admiration, but do not move us as works of art.” This, like Picasso’s “four years to paint like Raphael,” is the end of a tradition speaking. A couple of pages later we encounter an account of an unshackling as well as its provenances:

As a rule, primitive art is good . . . for, as a rule, it is also free from descriptive qualities. In primitive art you will find no accurate representation; you will only find significant form. Yet no other art moves us so profoundly. Whether we consider Sumerian sculpture or pre-dynastic Egyptian art, or archaic Greek, or the Wei and T’ang masterpieces, or those early Japanese works of which I had the luck to see a few superb examples . . . at the Shepherd’s Bush exhibition in 1910 . . . in every case we observe three common characteristics—absence of representation, absence of technical swagger [Picasso’s phrase for this is “learning to paint like Raphael”], sublimely impressive form.

And what was the Senegalese artist fighting? I wonder if, at some point, it would be something similar to what Bell, Picasso, and their contemporaries in Kolkata were fighting: “academic” conventions in art that, via Enlightenment pedagogy, become a default way of understanding art and representation almost everywhere by the late nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, for instance, the very Japanese prints that presented Van Gogh with a means of escape are becoming deadened by an oil-painting-like heaviness and sheen as the Renaissance ethos and neoclassicism move eastward and southward. The oppositional art movements that emerge in Asia and Africa don’t necessarily intend only to wrest indigeneity from the grasp of Western convention. In fact, the greater, say, the Indian artist’s quest for authenticity in the early twentieth century—that is, the greater the urge to represent a “pure” India—the more neoclassical or Western their aesthetic. No, the aim is to enter a conversation: with the Japanese print; with Japan; with classical and vernacular India; with the mask; with Picasso; with Paris. Picasso engages in this kind of conversation too, but one restricted to Europe, “Africa,” and the Palais du Trocadéro; for him, there is no Senegalese modernity that would add another resonance. The conversation his Senegalese contemporary or successor (Iba N’Diaye, Théodore Diouf) enters has to be a little more tantalizing, a little more real in an experiential, immediate sense, a little less utopian. Already, for the latter, categories like “Africa” and “Europe” are qualified in their usefulness.

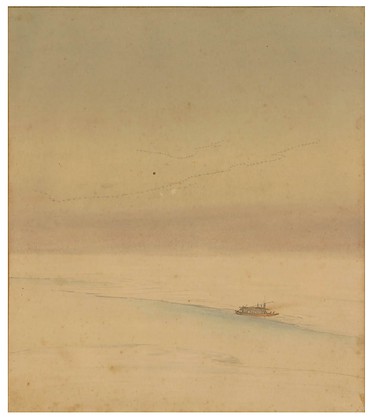

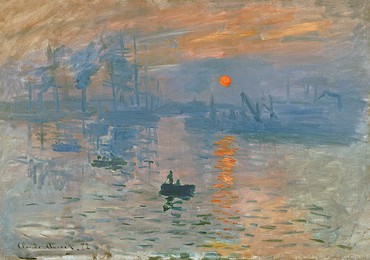

The faint open sore of the sun in Monet’s picture is not a vanishing point, it’s one among various points of entry—including the boats, the pallid reflection of the sun, the apparition of chimneys, and the ghostly outlines of dinghies—into this world.

It’s in this conversation that I would place Satyajit Ray. He is the last of the artists, beginning with Van Gogh and Monet, who worked, in a sense, as makers of block prints. We know of Van Gogh’s discovery of Félix Régamey, a Frenchman working as a faux-Japanese-woodblock-print artist in his capacity as a magazine illustrator. Van Gogh subsequently became a collector of Japanese prints (newly available in Europe in the late nineteenth century) and, for a while, served his apprenticeship by becoming a Japanese artist: that is, producing work identifiable by a “Japanese” subject matter and style. This enthusiasm was shared by his friend Paul Gauguin and certainly by Claude Monet, owner of a vast collection of Japanese block prints. Van Gogh called the Impressionists the “French Japanese.” This means that the Japanese modern is to be found not only in Japan—in Hiroshige, Hokusai, and their contemporaries—but also in Paris, in a different incarnation: as the French and Dutch Japanese. (Picasso, in Van Gogh’s terms, would be a French Spanish Senegalese or sub-Saharan.) But the field and its antagonisms are complex and intricate. They must also include, for instance, the Japanese from other epochs with whom Hiroshige was in dialogue: “modernity,” even as it was being articulated, was becoming period nonspecific. And it must include those Japanese artists who by the end of the eighteenth century were embracing Renaissance oil-painting-like realism. Among the most evocative of these are Maruyama Ōkyo and Kawahara Keiga; these too are “moderns,” though not modernists. Hokusai’s practice would be antithetical to a work like Keiga’s Nagasaki Harbour (c. 1833) and to the more reductive, quasi-photographic legacies of this lineage, as would the practices of Van Gogh and the French Japanese. This means that, from Asia to Europe, battle lines were being drawn whose demarcations and interests were separate from racial and colonial ones. On one side were the artists across the world who wielded realism as an instrument of power, on the other were those who were engaged, between themselves, in a give-and-take, an exchange of media, technique, and vision that created escape routes and intimations of freedom.

What does the exposure to Japanese prints and other lineages of texture and color do to Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Monet? First, it leads them to use a Renaissance inheritance—oil paint—against the grain of the purpose it served, of glossy verisimilitude and hyperrealism; to paint pictures not only composed of blotches but animated by the effervescence and lightness of illustrations and caricature, pictures possessed, however ostensibly melancholy their subject matter (such as Van Gogh’s bedroom), by a levity and warmth that is pleasurable without in any way being either comforting or uplifting—that levity being the gift of cultures that have long had an exposure to the idea of ananda, or bliss, or joy. Being a faux woodblock-printmaker is a joyous occupation, and it also means freedom from having to be a proper artist.

Second, it allows a painter like Monet to jettison the burdensome Renaissance legacy of perspective without necessarily creating paintings that look like flat surfaces. In his 1872 Impression, Sunrise, Monet, very subtly, gets rid of the vanishing point, the endpoint essential to the illusion of depth and distance, an illusion that allows painters to fashion their work as a window and, crucially, enables the viewer to stand outside the painting. The faint open sore of the sun in Monet’s picture is not a vanishing point, it’s one among various points of entry—including the boats, the pallid reflection of the sun, the apparition of chimneys, and the ghostly outlines of dinghies—into this world. We don’t examine these details for accuracy; we grow absorbed in them. The vanishing point, David Hockney points out in his comparison of a work by Canaletto to a depiction of an emperor’s visit in a fifteenth-century Chinese scroll painting, keeps the viewer in control and in a deliberate state of exclusion; the scroll, with its lateral unfolding, its unobtrusive undermining of the conventions of perspective, allows the viewer multiple entrances in. The sun is not an overlord in Monet’s picture any more than we are, or than any detail in the painting is. The weight between sun, boat, shadow, reflection, water, and viewer’s vantage point is equally distributed.

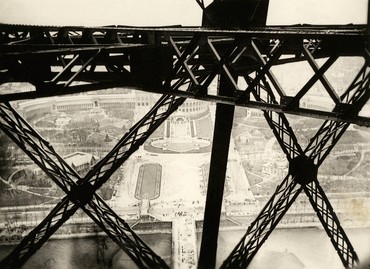

Hokusai borrowed from the perspectival techniques of the Dutch painters whose works became available in Japan in the eighteenth century, but his various takes on Mount Fuji, especially Fuji in the distance, aren’t really “perspectives,” in that their focus isn’t the mountain. Where the vanishing point in Canaletto’s Regatta on the Grand Canal (c. 1740) draws everything toward it and then presents the consequent arrangement to the owner of the painting, or the viewer, Hokusai’s Mount Fuji draws nothing toward itself. When we look at The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831), our eyes begin to move not toward the distance but from left to right, with the wave, the edges of froth, the chameleonlike Fuji (which, though immovable, mimics the wave through its white peak and blue body), the boats, and the endangered, battle-ready boatmen. The picture contains distance but the movement that interests it goes sideways. The blues and white of the wave and of Fuji, and the beige and light beige of the boats, comprise not depth but surface. This gives the print an extraordinary lightness, an absence of ponderousness. Fuji remains an interloper. You notice it suddenly. In his 1964 essay on the Eiffel Tower, Barthes quoted Guy de Maupassant’s dry remark on why he lunched regularly at a restaurant at the landmark “though he didn’t much care for the food”: “It’s the only place in Paris where I don’t have to see it.” That is, in Paris, the Eiffel Tower exemplifies the two poles of the Renaissance painting: the vanishing point and the viewer as overlord. Hokusai’s Fuji is hidden. It is Maupassant going into the tower. It won’t stand outside.

Monet, in whose block-print collection Hokusai figured, is reworking the great wave in Impression, Sunrise. The blister of the sun is his Fuji, eschewing centrality in, or exteriority to, the painting or the world. Maupassant was ten years younger than Monet, and his observation would not have been possible without Hokusai’s Fuji having entered the Parisian consciousness and—Monet’s painting is a living example of this—enabling an escape from the viewing subject: “It’s the only place in Paris where I don’t have to see it.” Fuji’s interface with the Eiffel Tower led Henri Rivière (fourteen years younger than Maupassant) to create the print series Thirty Six Views of the Eiffel Tower (1902), views seemingly occurring at various points in Paris and depriving the city, the tower, and the viewer of a sense of locus. In 1964, Barthes writes, “In order to negate the Eiffel Tower . . . you must, like Maupassant, get up on it and, so to speak, identify yourself with it. Like man himself, who is the only one not to know his own glance, the Tower is the only blind point of the total optical system of which it is the center and Paris the circumference.” Barthes is formulating a critique of the subject, the viewing “I,” that wouldn’t have been possible without the block print and Fuji.

“What sees,” Barthes continues, “remains hidden,” while “spectacles” comparable to the tower are “themselves blind”: that is, they are looked at but themselves cannot see. “The Tower . . . transgresses this separation, this habitual divorce of seeing and being seen”; and here he’s thinking of Hokusai and Mount Fuji. Rivière, in his own slightly twee way, is tackling the same problem: of making the tower present but hidden, neither entirely an observer nor entirely an object. Ludwig Wittgenstein, in his Tractatus (1922), had said, in effect, that you can’t “stand outside” language. Barthes’s meditation on the Eiffel Tower is a riff on this rejection of “standing outside,” and is prescient of Jacques Derrida’s “There is nothing outside the text” (De la Grammatologie, 1967). In Western philosophy and poststructuralism, these positions—especially Derrida’s pronouncement—begin to seem punitive, cautionary: they take on the Judeo-Christian sternness and the air of Enlightenment control that they wish to critique. It’s only when we go back to the emergence of modern nonrepresentational art, and to its provenances in the block print and visual and philosophical traditions around the world, that we experience the liberation, the jouissance, of rejecting the outside, where the outside comprises the observing subject.

The poet Tagore met the artist and art historian Okakura Kakuzō in 1902: they grew close, and Tagore invited Okakura to Visva-Bharati, the school and university he had created in the location he called “Santiniketan” (The home of tranquility). Okakura introduced Tagore’s nephews Gaganendranath and Abanindranath (both key figures in what’s called the “Bengal School” of art) to light brushstrokes in the Japanese style. The result was striking. Gaganendranath, whose gifts were already evident in the late nineteenth century, began to paint or draw verandahs, seated figures, and riverbanks—all from his milieu in Kolkata and Bengal—in a subdued wash and often in a black-and-white, comprising shadow and outline, that was replete with memory: a way of painting that was not so much representational as a type of formalism through recollection.

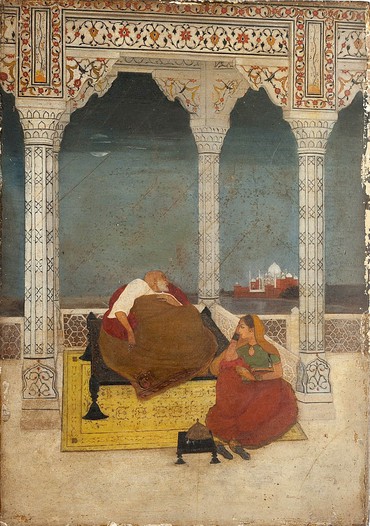

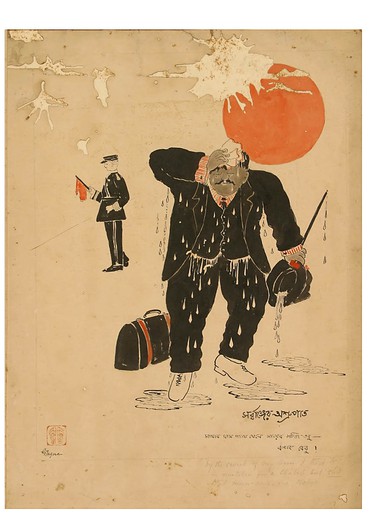

Gaganendranath’s younger brother Abanindranath, who studied at the Government School of Art, Kolkata, in the Western academic manner, turned early to the idea of, and quest for, an indigenous way of painting. He borrowed first from Mughal miniatures, as in The Passing of Shah Jahan (1902, an important year where these coordinates are concerned), a combination of miniaturist flatness, block-print-type dimensions, and, already, a Fuji-like Taj Mahal off-center in the distance that the dying emperor (who had had it built upon the death of his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal) is looking toward in exhausted yearning. The painting is undecided between the respective allures of Mughal flat surfaces, Renaissance situations and perspective, and Hokusai. Acquaintance with Okakura and, through him, with the tutelage of Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunsō (who was both a painter and a maker of woodblock prints) deepened Abanindranath and Gaganendranath’s attempts to create a hybrid “Indian Japanese” style (Shunsō’s mōrōtan or “vague” style is of particular interest to Gaganendranath, I think, in his illustrations to Tagore’s memoir Jiban Smriti [1912]); even the signatures that the younger artists at Santiniketan—many of them Abanindranath’s students—began to use in their paintings originated in the seals presented to Abanindranath and Gaganendranath by Okakura. Nandalal and Sudhir Khastgir reworked their own signatures as seal-inscriptions in small squares, with the Bengali letters resembling Chinese hieroglyphs. With Gaganendranath, experiments with brushstrokes led to bolder outlines in his satirical caricatures of the grotesque in Kolkata’s colonial and babu life: anarchic accounts, among the most remarkable images anywhere, that I think are also a part, in their mix of expressiveness and economy, of the block-print universe.

What Abanindranath’s students and Gaganendranath are seeking is not so much an “authentic” idiom, then; they are veering away from the Enlightenment they’ve been schooled in or exposed to and are aiming for a style—and, by implication, a way of living, viewing, thinking, painting—that involves being modern and Bengali at once, a style that is immediate, new, and a departure from the Renaissance proclivities for the spectacular. Line, space, and suggestion are marks of this style, and the Japanese block print and brushstroke are important to the formation of this Bengali modernity. And it’s feasible that Japan, and the Buddhism that the Tagore family is trying to recover from its own country’s history as well as from Japan and China, create meeting-points at which the family begin to become curious about similar projects in Europe: thus, Gaganendranath’s and Rabindranath’s interest in Kandinsky and the Bauhaus painters in the 1920s.

This is the Bengal that Satyajit Ray is born into in 1921.

To be continued in Gagosian Quarterly, Spring 2024.