Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergIs this old boot and guitar neck a Richard Prince sculpture?

Robbie RobertsonYes, yes it is! Good eye! But it’s all made in bronze and it weighs a ton.

DBWhen did you get that?

RRLast year maybe? One night, Richard and I had discussed doing a piece of art inspired by a guitar, and I had a bunch of guitar pieces and things lying around here so he said, “Just send me some stuff.” I sent a bunch of stuff, including some Fender Stratocaster necks. He had an old boot with paint all over it in his studio, so I guess he stuck the neck in the boot and sent me a picture and said, “Do you think this is a good start?” Did you see the shoe polish inside?

DBYes, I think it’s super cool. And it’s nice to have it in the studio. Normally music studios are so dark and kind of creepy.

RRYou think so? I love this studio. I wish you were here tomorrow because I’m doing playback on my new album with a bunch of friends.

DBI’m excited for the new album, even though I know it’s only one of a bunch of things you have coming out this year.

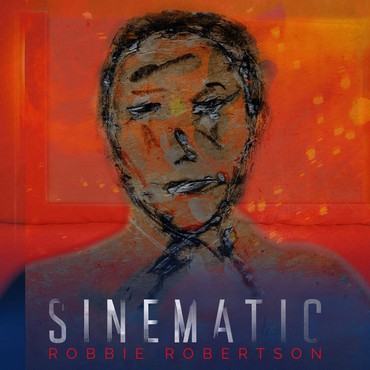

RRHa. Yeah, I’ve got this album, which I did the art for. I can’t wait to show you that. And a documentary, Once Were Brothers, which is named after one of the songs on the album. And then the music that I did for The Irishman, which is Scorsese’s new movie. Then it’s the fiftieth anniversary of the album The Band, which changed the course of music.

DBHalf a century! That’s wild.

RRI know. I can’t even relate. It’s just extraordinary. This was the invention of Americana. It’s now a genre, of course, but fifty years ago there was no Americana! The Band was also the first group ever to be on the cover of Time magazine. Did you know that? They’d done a cover about the phenomenon of The Beatles a year or two earlier, but The Band was the first group to be on the cover of Time just for its music. We were as surprised as anybody else.

DBHow does it feel to be on the other side of that half-a-century?

RRWell, there’s good days . . . [laughter].

DBI’ve spoken to a lot of people who had a front-row view on art, on music, on fashion, and most of them say when they look back they had no idea how big of a deal something was until they’re fifty years away from it.

RRI know what that feels like. There’s so much history under the bridge. I’ve been fortunate to travel such an inspired path all these years.

I witnessed two or three musical revolutions. not many people can say that. And some of it I was very responsible for, so i feel forunate in that.

Robbie Robertson

DBTell me: what’s the first story that comes to mind when you think about that path?

RRYears ago, I was having a fling with Edie Sedgwick and we lived at the Chelsea Hotel together. I would go with her and Andy Warhol to all these things, all these happenings. It was a period when music and art and everything was all flowing together completely. There was no separation.

DBHow has it gotten different since 1969 at the Chelsea Hotel?

RRIt’s different, but in ways those connections live on forever. For me in particular, those worlds still revolve around one another.

DBWhat was your introduction to the art world?

RRPlaying with Bob Dylan. I came to New York to live when I was twenty, and that’s when I hooked up with Dylan. The poets and the music and the art world and all these things were swirling around. I was there the day Warhol gave a big double Elvis painting to Bob Dylan. Bob and I were at our manager’s apartment in Gramercy Park, and Andy came over with a bunch of people carrying this big picture. When they unfolded it and showed it to Bob, he was like, “Oh. Okay.” Andy was a little shy and uncomfortable about the situation, so he left and Bob said, “What the hell am I supposed to do with this? Am I supposed to put a big picture of Elvis Presley on my wall? That’s like Chuck Berry putting a picture of Little Richard up on his wall.” So he said to Albert Grossman, his manager, “I don’t want this picture, but I’d like a couch. I just got my own apartment and I need a couch.” He traded Grossman that picture for a couch. Now that picture is in the Museum of Modern Art. Probably worth more than $60 million.

DBMaybe even more.

RRMaybe even more.

DBWhat do you think that couch is worth?

RRThat couch isn’t in great shape! In fact, it ended up out on the curb. That wasn’t a great trade.

DBIn your book you mention meeting Salvador Dalí.

RRYeah, I would go with Andy and Edie up to Dalí’s penthouse at the St. Regis hotel. We’d go up there at midnight or one o’clock in the morning and Salvador would be entertaining. He was such an amazing character. We got up there one night and on the dining room table were a bunch of incredible drawings of horses and other animals. I said to Edie, “Wow, look at this!” And she said to Salvador, “Is this something new?” And he said, “It’s a new masterpiece I’m working on. And if you notice the horses have no heads.” Then Andy said, “Wow, maybe I should do a thing with horses.” Salvador turned around and said, “Why do you need to do a thing with horses? You have soup cans and lady shoes.” Andy said, “I think we should go.”

DBYou think he was offended?

RRIt wasn’t offensive really, but it wasn’t a compliment either.

DBHow was writing your book? Cathartic?

RRIt was therapy. It was all of the things you’d think it would be. Also, one of the hardest things I’ve ever done in my life. I wrote every word in it. I had an editor who helped me shorten it, because I overwrote the hell out of it, but there were no other writers. I’d never done anything like that. Now I’m deep in on volume 2. The publisher said to me, “You can’t write your autobiography and end it when you’re thirty-two.”

Marty [Scorsese] always said, “The picture and the music: There’s no difference.”

Robbie Robertson

DBThey’re not wrong!

RRI witnessed two or three musical revolutions. Not many people can say that. And some of it I was very responsible for, so I feel so fortunate in that.

DBYou’re working on the artwork for the album that comes out in the fall. Have you ever done any artwork before?

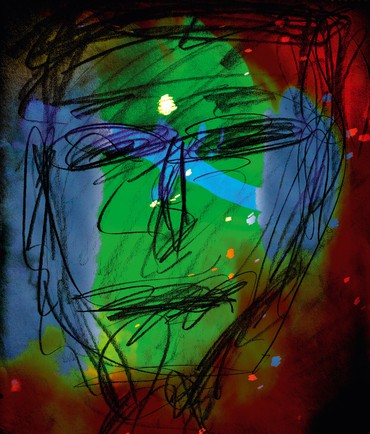

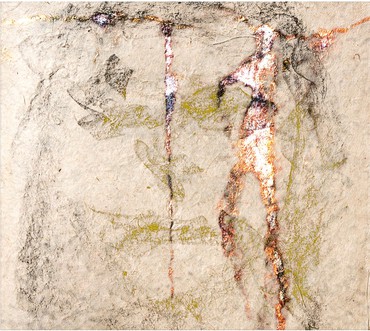

RRI’ve been doing artwork all my life, but I’ve only done it for things that were personal. It was never, like, in a show. Each song that I wrote for this record, I saw a picture. I saw an image. I’d do drawings and photographs and integrate them sometimes. It’s very much mixed media. At the same time, there’s something very classic and primitive in there too. It’s kind of like my music.

DBThat was going to be my next question: is your process of making music similar to your process of working on art?

RRIt is. You have a blank canvas and then you have a germ of a small idea and you put a couple of dabs on the canvas and think, “Oh, this is giving me an idea.” It’s the same thing with writing a composition. You sit down with a guitar or a piano and have no idea; then you put your fingers on the strings or the keys and think, “I’m feeling something in this.” It’s like some kind of a silent vibration starts to happen. It leads you down the path and you keep following this thing. You put all your trust in it and sometimes you come out the other end with something you love and sometimes you come out the other end with something that you think, “Ehh, nice try.”

DBBob Dylan plays and paints.

RRHe did the cover for The Band’s first album! I asked him to because years ago he gave me a cool painting of an American Indian guy, close up, and in the background was an Indian girl on the back of a horse with a white man, riding away. I thought it was so terrific. I thought, “Wow, this is really telling a story like our songs do.” So I asked him if he wanted to do a painting for the cover of Music from Big Pink. He said, “Alright, let me see what I can do.” So he went off and a little while later he came over to my house and he had this picture and he said, “Does this work?” It was hilarious. And cool. And unusual. And nobody had had an album cover, ever, that looked like that. He still has that painting, by the way. I heard he wants a lot of money for it. Maybe he’s getting back for that Andy Warhol thing, I’m telling you [laughter]!

DBWas it easier to write the book, to paint the album drawing, or to do the album?

RRAll of these things, they’re all interwoven. I was working on the music for Scorsese’s new movie, The Irishman, and all of a sudden the songs are reflecting that story. We’re working on the documentary based on my book—Scorsese is the executive producer on that too—and it’s all bleeding together. I’m writing a song, trying to finish a song, I’m doing drawings, I’m coloring, I’m taking pictures, I’m doing all this stuff, and everything starts to become a big year of artistic involvement. Usually people of my generation, at this point, are going the other direction. They’re mellowing out. But I’m just ramping up.

DBThis isn’t the first time you and Scorsese have worked together.

RRI started working with Scorsese on Raging Bull [1980], and I’ve done music for most of his movies over the years since. Every time, I say to myself, “Oh my god, I don’t know if I can do this.” Every. Time. But then, of course, I love working with him.

DBWhat’s that creative process like?

RRIt’s different every time and that’s why it’s challenging. It’s fun, and we go into most of these things with a blank canvas. It’s like, “What the hell does this movie sound like? What are we going to do this time?” Sometimes I see a script or clips, but it’s always a different process. The score for The Irishman goes back to the French gangster movies of the early ’50s, which gave me a sound I could start with. Marty always said, “The picture and the music: there’s no difference. They’re all the same.” Sometimes I’m just choosing songs that will play in a certain scene. Sometimes I’m choosing a piece of classical music. Sometimes I’m making the music. Sometimes it’s all of the above.

DBWhat other artists do you like?

RRYeah, I like Grotjahn. Mark is a friend of mine. I like Thomas Houseago. I like Koons. I’ve spent some time with Jeff and he’s explained to me how some of those pieces come together, like in his Hulk sculptures. He showed me in the back of one of the sculptures how there’s a little hole there and a certain key goes in that hole and when you turn the key all the pieces come apart.

DBLet’s talk about the art you’re working on.

RRI take a lot of pictures. One of my favorites is a photograph of the reflection of my swimming pool up against the glass at my house. It’s abstract. Basically, I’m gathering pics all the time, and then I’ll draw or paint on top of them at home or here in the studio.

DBDo you have the same feeling at the end of an amazing painting as you do at the end of an amazing song? It’s the same validation?

RROh yeah. This Scorsese movie, The Irishman, is based on a book called I Heard You Paint Houses [by Charles Brandt]. In the mob, when a guy would go to a hitman to knock someone off, he’d say, “I heard you paint houses.” And the hitman would say, “So what do you need?” For the movie I wrote a song called “I Hear You Paint Houses,” which is a duet with Van Morrison. Here’s the piece of art that I did for it: a picture of a gun, which I own, placed on top of a close-up pic I did of a flower. So all of the color comes from the flower. It’s just that conflict of niceness and the gun and the hitman.

DBRobbie, where are you from?

RRMy mother was born and raised in the Six Nations Indian Reserve in Canada and my father was a Jewish gangster, so between those two worlds it wasn’t for sure I wasn’t going to end up in prison for the rest of my life. There’s a song called “Dead End Kid” that I wrote about what people like me were called back then.

DBDo you ever go back home? I’m sure there were a lot of kids in a similar situation who ended up as “dead-end kids.”

RRYeah, a lot of them it didn’t work out for. When I was a kid growing up, somebody would say “I’m Italian,” or someone would say “I’m Irish,” and then they’d say “What are you?” I’d say, “Let’s not go into it.”

DBDid you seek any advice from any of your artist friends while you were working on your art?

RRNope [laughter].

DBAre you excited to have some of your art come to light?

RRYeah. It’s fun for me to pull that rabbit out of the hat, you know?