Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Most art historians have to take an aesthetic or intellectual viewpoint. They never, never, never try to go into the soul of an artist. Of course, you can’t really go inside the soul of a man; you can only go into your own soul in the end. That’s why [Edvard Munch, 1974] is extremely personal.

—Peter Watkins, 1975

That most moments were substantially the same did not detract at all from the possibility that the next moment might be utterly different. And so the ordinary demanded unblinking attention. Any tedious hour might be the last of its kind.

—Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping, 1980

A maddening task, writing about filming painting. As they meet, these three unruly media inevitably scramble, tussle, scrape against each other’s limits—and their possibilities. After the scramble, there lingers the unavoidable feeling that something, the medium-specific and unannounced spark that powers each of the three, escapes being captured—and that is what an artist strains to bring to the surface: a lovedeath, the hidden machinations of a delicate process. Very few have faced it. What is it? The black point. The silence that emerges when a fragment melts into a mirage of a whole, or when talk becomes flesh. The unrepresentable. Void. The word (for instance: “love,” the unbroached, shadowy state in Henry James’s “The Beast in the Jungle”) that, in remaining unspoken by the writer, conjures up a terrain, vast and blooming beyond conscious will. The shivering detail in a painting that takes on its own ornery but beautiful life—away from plot, away from the foreclosing details of identity, and into the realm of purest spirit, propulsive drive. Especially in the best cinema about painters, it is the point at which the artist, glimpsing a long-pursued point of apotheosis, turns suddenly away from total revelation and chooses a secret, privacy, a sneaky obfuscation—not out of cowardice but out of a moral respect for the daily that changes dissipation into conversation, chaos into the briefest of strange harmonies. That, I think, is what my favorite films about painters achieve: Peter Watkins’s Edvard Munch (1974), Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life (1956), Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (1991), Victor Erice’s Quince Tree Sun (1992), Robert Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), and Raúl Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (1978). It is the sense that these films are not giving you what you, the viewer, initially thought you desired. Come for the dance, stay for the echoes of footsteps across the canvas.

Film has a pronounced inferiority complex when it comes to showing any artistic process beyond itself. It can signify high culture, learning, unimpeachable tradition, by depicting a monstrously sensitive Van Gogh writhing with a razor blade dangled near the infamous ear, or a painter contorting a nude pair of breasts-stomach-ass (barely a woman) into so many torturous positions that he captures “her essence,” his ideal of platonic plastic beauty, curves and slopes and rosy hues that only he could mine. Ever mounting are the triple clichés of film: 1) its only function is entertainment, straight-arrow narratives loaded with effects and sugar and hype; 2) it is a pure index of (what is perceived as) reality—we see all the steps that it takes to make a painting, all “tricks” explained and revealed, and thus film gives us, unvarnished, the truth of life itself, as André Bazin saw it; and 3) painting is leagues above film, in terms of difficulty and individual expression, since many of the popular films around painters are only a few degrees removed from story-book-time starring Vincent and Pablo and Jackson, action delineated according to the Griffith/Spielberg aesthetic complex: the shot-reverse-shot, the melos in the drama, the myths.

Basically, narrative movies, to hook most audiences, have had to flirt with the overtones of myth. A necessary evil, this. Myth—at its sweaty, vulgar, Hollywood purest—is what gives longevity to a film like Minnelli’s Lust for Life, that iconic study of Kirk Douglas’s gritted teeth and sweaty brow. It’s also a knotty, more-than-meets-the-eye masterpiece, to which we’ll loop back. But for now, let’s just say that Lust for Life (made at the height of the high mythologizing that accompanied American Abstract Expressionism, and that’s no coincidence) set the tone and the questions that all subsequent narrative films about painters were to pursue: why make filmed works on artists who shirked away from or were contemptuous of photography? How much do we show of the personal, how much of the work—and are the two separable? When we narrate somebody’s life, how do we mitigate the inevitable simplifications for story’s sake? That last question is already thorny when the person in question is, say, a real-life activist (Milk, 2008) or a fictional cooking-cleaning-trick-turning housewife (Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, 1975); what happens when the person is an artist, for whom reality feeds into an alternate dreamworld of lines and colors and ripples poured back into reality, such that many “persons” pile up, many realities contaminate, all of them inseparable from the very forms through which their story is shot? Which is the real Van Gogh? Is the artist under interrogation in Jacques Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse (1991) the actor Emmanuelle Béart, Balzac’s fictional painter Frenhofer (Rivette’s film being based on Balzac’s novella “Le Chef-d’oeuvre inconnu [The unknown masterpiece], of 1831), or Rivette himself? Does the uncut “truth” of any of the three exist?

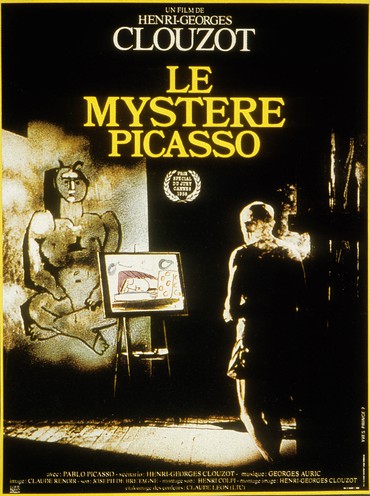

To wade into the morass, we must inevitably confront myth. We can’t get rid of it. Its romanticism, its passion, its sweetened memories, its seductive lies. Take, for a case study, one of the ultimate myth-makers: Pablo Picasso. The same year Lust for Life racked up Oscar nominations and was raved over by ultrabourgeois, gatekeeping, tastemaker magazines like Time and Life, a strange new cinematic experiment, billed as a “documentary,” premiered at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival: Le Mystère Picasso. It was an unprecedented collaboration between Picasso and the popular tradition de qualité French director Henri-Georges Clouzot (The Wages of Fear, Diabolique). As François Truffaut explained in his original 1956 review of the film,

Clouzot, whose avocation is painting, has wanted to make a film with his friend Pablo Picasso for a long time. They were held back as long as they were by a fear of having to respect the conventions of the “art film”—didacticism, dissection of canvases, the recounting of anecdotes, of being boring by having repeatedly to show first the artist at work and then the finished canvas. A special ink made in America that was sent to Picasso by some friends settled this last problem. Clouzot was able to place the camera, not behind Picasso’s back or next to him, but behind the canvas. Instead of watching Picasso paint, as would a visitor to his studio, we are present during the pure creative act without the intrusion of any external or picturesque element. This purity, this respect for the artist and his material, is pushed so far that there is no commentary to “instruct” or distract us.1

Truffaut goes on to praise Le Mystère Picasso as “a great work by reason of the calm genius of its character, by the beauty of the film’s material, and because of the filmmaker’s ingenuity.” High praise from the unruly young Turk on the French film scene, a twenty-four-year-old upstart whose print outlet, Cahiers du Cinéma, routinely heaped abuse on directors like Clouzot, those stalwarts of studio filmmaking whom they derided as the “cinéma du papa.” Nevertheless, one has to press what Truffaut means by his belief that “we are present during the pure creative act without the intrusion of any external or picturesque element.” Quite the opposite: the less someone appears, the more present they are. (Isn’t this the basic thrust of Truffaut and company’s auteur theory?) In Picasso’s virtuoso curves as documented by Clouzot, we have the illusion of emergence and spontaneity, the same arresting but false myth as that of the fate-forged genius above the rest of the antlike world, and doomed to be tormented.

Le Mystère Picasso is less a demonstration of Picasso’s “pure creative act” and more brilliant advertising of the act. It was shot over a grueling period of months, not only creating one myth—that Picasso rattled off these paintings in seemingly a day, one after the other (which, yes, he could do)—but confirming another: that he possessed a genius that was a kind of miracle reservoir for him, allowing the perfect shapes to pour untrammeled from brain to hand to canvas. There are quirky dramatic interludes in which Clouzot eggs Picasso to “beat the clock” and complete a painting before the film in the camera runs out (moments that Truffaut derided as “not in the best taste” and “a circus act in the middle of a concert.”) There is a poundingly dramatic orchestral score by Georges Auric (which Éric Rohmer, writing for Arts, found “rather mangled and overwhelming”).2 There is one hell of a show-stopper: Picasso’s torturous attempt to paint and repaint a beach scene, framed to the dimensions of the ultrawide CinemaScope aspect ratio, in blaring oils and colors. All of these indicate the presence of an auteurist director tipping reality to what he wants it to be. We are not quite in the fictive terrain of Lust for Life, but this is not an unworked, free presentation—certainly not just the facts, ma’am.

In all of the staged discussions between Picasso and Clouzot on artistic method and intent, Picasso keeps riffing on one word: “risk,” the kissing cousin to “myth.” Risk suggests danger, thrills, adventure, setting off into unknown aesthetic terrain, planting one’s flag there and colonizing it in one’s name. The painter constructs a fiction around himself, remaining guarded while letting his hand—and just that, the hand, trained in the finest schools of looking and being and loving around the world!—continue its loud work of pleasantly stunning the viewer and, even better, upsetting the arbiters of good taste at any given point in time. Meanwhile, the real process of painting remains obscure: why these figures? Why those splotchy inks? Le Mystère Picasso reveals something about what it means to be a painter, yes, but do we, as Clouzot suggests in his opening narration, delve into the mind of the artist through his hand, his work, his pure traces? Not really. The other side, perhaps, would have been provided by Françoise Gilot, or perhaps Picasso’s friends in the French Left, or his butcher. None appear.

The spiritual and psychic reasons for fighting the canvas become the $64,000 question of another tall mythic work in the French cinema of painting, Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse. Balzac’s novella Le chef-d’oeuvre inconnu, a nineteenth-century story set in the seventeenth century, is here set in the postmodern 1990s. What a time crunch! We explore the myth of love—or, more precisely, of desire—and how it gets mixed up with not only “the artistic process” but also commerce, wealth, bargaining, the parallel circulations of value and aesthetics. Myth is expanded, but another myth is also gratuitously extended: that of mystery, particularly as it relates to the artist’s self-knowledge and knowledge of women in general.

The allure of Balzac’s novella lies in the nature of Frenhofer’s titular painting: it is fundamentally misunderstood in its time, yet we in our time don’t know what it looks like, either. It is a work of perfection that surely we, reading it long after 1831, can understand to be the first modernist painting, but that propitious, dutiful, smart painters of Frenhofer’s time, like Balzac’s fictionalized Poussin and Porbus, can only see as so many jumbles of lines and hazy colors. But what makes us think we’re so different from those two, with their limited historical vision? Frenhofer’s painting exists perfectly in our minds as text and only text. Rivette ups the stakes by cinematizing the story, using the medium of photographic reproduction, of seeming reality, in order to reveal—what? That within struggling-painter films, cinema is capable of the richest unrealities, and of gaping absences that score our souls more deeply and widely, perhaps, than the painting that is our central focus. In Rivette as in Balzac, the painting is kept at bay, it is not shown (to us). Both the model (Béart) and the painter’s wife (Jane Birkin) recede from it when they see it, and the painter (Michel Piccoli) ends up stashing it in a hole in the wall, which he then covers up with brick and mortar, sealing it forever. Only he knows where it lies; only the three of them know what it looks like.

La Belle Noiseuse, though invigorating and absorbing to watch, strikes me as strangely basic and conservative for Rivette, somewhat of a downgrade from the scarier, boundary-breaking experiments in cinema that he was conducting from the late ’60s into the mid-’70s: L’Amour fou (1969), Out 1 (1971), Out 1: Spectre (1973), Céline et Julie vont en bâteau (1974), Duelle: une quarantine (1976), and Noroît: une vengeance (1976). “I want the invisible,” as Rivette’s and Piccoli’s Frenhofer says. These, perhaps, are the unknown masterpieces (gradually becoming more known) that the painter in Noiseuse is straining so desperately to make. But when Rivette turns his conscious eye to the act of painting itself, as a stand-in for all art, all he uncovers (not without a trace of irony and self-awareness) are the beats of an age-old tale, older than Balzac: the desire to master nature and people (particularly beautiful women), the copyrighting and bartering-off of the finished product, the toasts to another job well painted.

I do my best to make what I feel—my impressions and sensations—happen on screen. . . . That said, it’s almost impossible to have been a painter and to no longer be one. Painting taught me . . . to mistrust painting in films.

—Robert Bresson, interview on Four Nights of a Dreamer, 1972

After a certain point, the myth buckles under its own weight and must give. It’s unsustainable. The cracks in the image of the lonely, blustery, genius painter have been accumulating ever since the miraculous ones in Raúl Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (1977); one of the biggest cracks yet announces itself in Der Maler (The painter, 2022), by Oliver Hirschbiegel, Albert Oehlen, and Ben Becker. It’s hard to settle on what this film even is. It would purport to move like a conventional behind-the-scenes documentary on a painter, in this case Oehlen, making a work of art from blank canvas to “Finished, for now.” But it’s weirder: Becker, a German comedian and actor, has been hired to impersonate Oehlen, improvising what Oehlen would say to himself in the process of making the painting that we see come to life. And because the film never questions Oehlen’s presence or Becker’s impersonation, viewers who don’t know what Oehlen looks like may not realize that the man they’re following isn’t him until late in the film—if at all.

The “real” Oehlen (but then, what’s real at this point?) never appears on-screen. He remains entirely off-screen, creating the painting that serves as the model for Becker’s painting. Oehlen’s every brushstroke is observed by Becker, who adds his own actorly flourishes to explain why he, the Painter, is making this brushstroke or adding that color: “It taunts me!” “Fight fire with fire; fight smear with more smear!” These hilarious, magnetic asides are a mix of genuine inspiration, hilarious stand-up, pop-self-psychoanalysis, and parodic bluster. Oehlen’s off-screen blueprint painting was destroyed after the principal shoot was finished.3 Between periods of painting, the intense, expert voice of Charlotte Rampling “explains” Oehlen’s process in half-poems: “A kind of drunkenness, ecstasy, is making me stumble as if I’m in a fog, trying it out, shaking, stirring, spraying. You can’t stop. Mounds build up. Tracks of slime. Nodules at the same time the names and the terminology make themselves known. Medieval yellow.” The squirming language is often touching nonsense, but a point emerges from it: the stumbles, the ecstasies, of teeth-gnawing creation. Becker’s Oehlen tramps around a finished exhibition of his newest work in cowboy boots, sunglasses, and a Texas ten-gallon hat, like an ass-kicking Jean-Pierre Melville of the twenty-first century, or Richard Prince’s Marlboro Man if he hung up the saddle and picked up the brush. It’s all a grand put-on—but it’s also a real document, and quite an entertaining one, of the traces of painting as they briefly reveal themselves. What’s sneakily smart about Der Maler (what a title—the one and only!) is that it reverses the usual purpose of painter-at-work narratives: here, for once, it is paintings that are used to reveal the unruly nontruths inherent in a seemingly automatic-truth medium like the cinema, and not the other way around. The gargantuan white man rages against the elements to finish the work in time for exhibition. It’s a string of evasions, the logical next step after Orson Welles’s F For Fake (1973), about the Picasso forger Elmyr de Hory. Here, what would have once been decried as imitation or forgery is in fact, in James’s words, “the real right thing.”

But if the “real” is destroyed, the real is still somewhere, far off, always striven for. Does this not constitute another myth? Well, yes, that’s the point. We destroy myths and erect new ones in their wake. Nothing escapes total mythologization. What we must always pursue is the unshown, the blissfully and sublimely blank. As the painter friend says in Bresson’s indescribably beautiful Four Nights of a Dreamer, “Neither the object there, nor the painter there, but the painter and the object which are both not there. Their visible disappearances make the canvas.” As for us, the viewers, we must be kept out of what truly goes on in the painter’s mind: the history they consciously struggle against, the people and places they have loved and hope to love—and have lost. The painter soon learns, finally, that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master;/so many things seem filled with the intent/to be lost that their loss is no disaster.”4

Here we slip into the erotics of filming painting. Their codes demand discretion. “I didn’t know conversations could be so erotic,” says a character in one of the simplest and most exciting films of recent years, Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021). Sex and painting are the two phenomena that film cannot hope to capture with any measure of fidelity to their real-time experience, and for similar reasons: the fear of intrusion, of being inside a place where one does not belong, that is, the artist’s interiority, the artist in process, with flaws and insecurities hanging out openly before the chance to revise, adapt, backtrack, finalize. Recall, for instance, that Cézanne wouldn’t let people see him painting. I like to think that for him, those quiet shifts, when exposed, contained fatal whiffs of the pornographic; what he wished to be known for, as every great lover or artist does, was the final product, the shivering apple, not the hesitancies, the nervous gestures toward an imagined profundity that will inevitably come out strained if one is too conscious of an audience beyond oneself and the canvas (or, in the case of sex, beyond oneself and the judging, mercurial partner). There cannot be an audience—not yet. This is the reason for the intense charge of watching films about painting—especially in a cinema, an occult space of clandestinity and vision-swallowing.

No better film to watch in this “site of availability,” this “urban dark” that makes possible “the body’s freedom” (Roland Barthes), than Watkins’s four-hour biopic on the life of Munch.5 The film, which traces about thirty years of the artist’s youth and development, certainly romanticizes, but it neither mystifies an art-for-art’s-sake credo that ignores the political nor raises the tortured-genius image to hosannas and heights. Instead, it looks hard, soberingly, and dartingly, and with neither sanguine pity nor sardonic distance, at the reasons why somebody might seek out art when their life doesn’t take solid shape around their yearning wants.

Edvard Munch fractures time. As a narrator (Watkins himself) recounts episodes from Munch’s traumatic boyhood (the death of his sister Sophie, from tuberculosis, at the age of fifteen, his doomed love affairs, another sister’s mental illness), the film jumps freely and without warning across scenes from Munch’s youth and from his present as a working painter. The personal, the political, and the aesthetic all exist as if across an ice sheet, crackling, time becoming miraculously horizontal. Watkins advances earlier directors’ formal experiments in fractured time: Alain Resnais (Muriel, 1963, and Je t’aime, je t’aime, 1968), Richard Lester (Petulia, 1968), and Nicolas Roeg (Walkabout, 1971, and Don’t Look Now, 1973). As he himself said, “I believe that we are all history, past, present, future, all participating in a common sharing and sensing of experiences which flow about us, forwards and backwards, sometimes simultaneously, without limitations from time or space.”6 This is the type of free-flowing movement that only the cinema can provide, a movement that Virginia Woolf predicted would be its ultimate radical innovation: “We should see violent changes of emotion produced by their collision. The most fantastic contrasts could be flashed before us with a speed which the writer can only toil after in vain. . . . The past could be unrolled, distances annihilated, and the gulfs which dislocate novels (when, for instance, Tolstoy has to pass from Levin to Anna, and in doing so jars his story and wrenches and arrests our sympathies) could, by the sameness of the background, by the repetition of some scene, be smoothed away.”7

Edvard Munch goes deep into the personal, which you’re not supposed to do in a serious film about the process of painting. Watkins, however, makes richly compelling arguments that Munch’s relationship with a Norwegian married woman, known in his diaries and in the film as “Mrs. Heisberg,” had an insurmountable impact on how he attacked the canvas. As Watkins says in a conversation with his biographer, Joseph A. Gomez, a “primary” level of Edvard Munch springs from “my own feelings, twisting in and out of what I perceived to be Munch’s feelings. Or rather, let me say, I never tried to make decisions about what Edvard Munch ‘felt’—at a very early stage, I realized the utter futility (and arrogance) of this—instead, I tried to fuse my feelings about my childhood, my own sexual experience, my own work, into a recreation of various events that occurred to Munch.”8 We only have ourselves to work with. Film directors, if they are inspired, access not the beloved soul of the painter but their own.

This, few can bear. For there lies again our old friend the lovedeath, the abyss. For four solid hours, Watkins manages it, in a film that embodies all the qualities I desire in cinema: being politically and artistically challenging (art = politics), self-aware (i.e., transparent), emotionally moving, brutally personal (Edvard Munch invites me to connect Munch’s story to specific events and emotions and complex people in my own life), free-form, jazzy, out of sync, out of whack, out of time and yet timeless, unhectoring, unobvious, made with human feeling, aware of its subject’s limitations in relation to other classes and to women, aware of its subject’s exceeding romanticism in relation to the lower class and to women, brutally critical yet not wholly dismissive (a distance that’s not quite objective), roving, roaming, wandering, refusing to distinguish between past present and future, non-thesis-driven, warm, tender, bitter, dejected, cathartic, complicated, delicious, and just plain beautiful. And that’s the tip of the iceberg.

So what lies at the end of the road of myth? We happen upon, surprisingly enough, another film on the artist with whom we began the journey: Pialat’s Van Gogh, made in the same year as Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse. It’s the tonal opposite of Minnelli’s Lust for Life in every possible way. Instead of following the arc of Van Gogh’s life, Pialat burrows into the artist’s final sixty-seven days, in Auvers-sur-Oise. We get none of the writhing, desperate Van Gogh seen in Douglas’s brilliant performance; instead, Pialat casts the French pop star Jacques Dutronc to embody a hushed, puttering Van Gogh, who tries to sell his paintings, fails, and turns to a debauched (but unremarkable) world of sex, drink, and dance in bars and brothels to suppress the pain of his lack of acceptance. We are kept at a distance from Dutronc’s Van Gogh; we don’t know what goes on in his head, why he acts the way he does. He doesn’t physically appear for most of the film, we hardly see him painting, and the suicide seems like a quotidian gesture in a life chock-full of them. Pialat’s innovation: presenting the ambience that affected Van Gogh as he painted, not the literal act of painting. No less than Jean-Luc Godard was impressed by this daring shift in focus for a film on painters, as shown in a rare effusive note that he wrote to Pialat following the French release of Van Gogh:

My dear Maurice, your film is astonishing, totally astonishing; far beyond the cinematographic horizon covered up until now by our wretched gaze. Your eye is a great heart that sends the camera hurtling among girls, boys, spaces, moments in time, and colors, like childish tantrums. The ensemble is miraculous; the details, sparks of light within this miracle; we see the big sky fall and rise from this poor and simple earth. All of my thanks, to you and yours, for this success—warm, incomparable, quivering.

Cordially yours, Jean-Luc Godard.9

This is not your traditional death-of-a-genius film. None of the clichés surface. That’s not to say it’s better than Lust for Life; the two are complements for each another, and I would say that the pursuit of an all-encompassing, detail-obsessed love of the terrain around the viewer, a full awareness of surroundings that bolsters the lonely subjective, is the same for both Minnelli and Pialat. Naturally, the two use considerably divergent means and languages to fulfill that love: Minnelli loves to project masculine angst onto inhospitable environments, while Pialat dials back within implosive, coiled private worlds. Yet both of these films seek out the unheralded ripples of physical experience, the revelation, for ever so brief a time, of the atomic structures of love, the artist’s final possession. Or rather, her state of being possessed.

1François Truffaut, The Films in My Life, 1975 (Eng. trans. Leonard Mayhew, Boston: Da Capo Press, 1994), p. 201.

2Éric Rohmer, “Le Mystère de Picasso,” Arts 572 (June 1956). Available online at https://letterboxd.com/notericrohmer/film/the-mystery-of-picasso/ (accessed July 7, 2022).

3Picture Tree International, press notes for Der Maler, 2022. Available online at https://www.picturetree-international.com/films/details/the-painter.html#pdf=81c04c299e54bd0dad2c0d690662c56f (accessed July 7, 2022).

4Elizabeth Bishop, “One Art,” 1976, in The Complete Poems 1926–1979 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983), Available online at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47536/one-art (accessed July 7, 2022).

5Roland Barthes, “Leaving the Movie Theater,” in Phillip Lopate, ed., The Art of the Personal Essay (New York: Anchor Books, 1995), p. 419.

6Peter Watkins, in a tape-recorded conversation with Joseph A. Gomez, his biographer, while Watkins was reediting the cinema-release version of Edvard Munch, August 4–9, 1975. In the booklet for the DVD release of Edvard Munch, 1974, p. 11.

7Virginia Woolf, “The Cinema,” The Nation and Athenaeum, July 3, 1926, p. 383.

8Watkins, conversation with Gomez, p. 13.

9Jean-Luc Godard, in a letter reproduced in “Sabzian Selects (Again): Week 25,” May 10, 2021. Available online at https://www.sabzian.be/event/sabzian-selects-again-week-25#footnote2_psb51m9 (accessed June 30, 2022). Note translated from the French by Craig Keller.