James Lawrence is a critic and historian of postwar and contemporary art. He is a frequent contributor to the Burlington Magazine and his writings appear in many gallery and museum publications around the world. Photo: William Davie

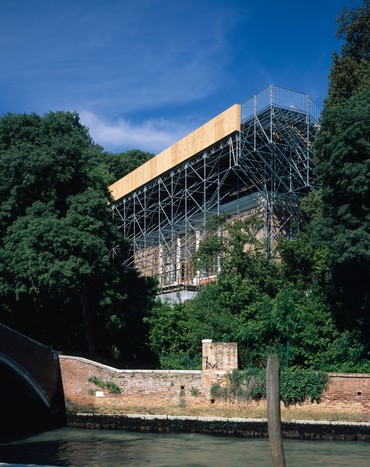

In August 2017, the sculptor Marcus Taylor approached Caruso St John Architects with an idea for the Venice Architecture Biennale. The British Council was seeking proposals for the British Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale, and the deadline loomed. Taylor proposed building a platform, open to the public and supported by scaffolding, over the pavilion so that it would encircle the apex of the roof. In stark contrast to conventional proposals for a national pavilion at the Biennale, the building itself was intended from the outset of Taylor’s proposal to be open but undeveloped: an environment for recollection and discussion rather than the setting for a particular curatorial proposition. Taylor and Caruso St John submitted an initial proposal comprising fewer than two hundred words and two illustrations: a photograph of a nineteenth-century church in India, ruined and almost submerged by monsoon floods; and a lithograph showing St. Isaac’s Cathedral, St. Petersburg, under scaffolding. This pithy, unorthodox, enticingly provocative idea eventually became Island, Britain’s national contribution to the 2018 Biennale.

Island is not entirely new territory for Taylor, Adam Caruso, and Peter St John. Taylor had earlier commissioned Redshank, a one-bedroom cork-clad beach house completed in 2016. Redshank stands on steel poles above coastal marshland in the east of England. Taylor collaborated with Lisa Shell Architects on the design, which allows the marsh to reclaim the land on which the house stands. Redshank’s form suggests not only its namesake wading bird but also a type of offshore antiaircraft platform from World War II known as a Maunsell Sea Fort. These curious structures were decommissioned in the 1950s, after which some of them housed pirate radio stations. One of them constitutes the self-proclaimed Principality of Sealand, which has maintained a quixotic claim to statehood since the 1970s.

In 2016–17, Taylor also collaborated with Caruso, St John, and Rachel Whiteread on a shortlisted proposal for a Holocaust memorial planned for Victoria Tower Gardens, next to London’s Palace of Westminster. Their design envisaged an open area punctuated by resin casts after a nearby memorial commemorating the emancipation of slaves in the British Empire; and an enclosed, subterranean arena intended for contemplation, with discrete areas reserved for listening to recorded testimonies from survivors. As with Island, the design proposed a binary division—higher and lower, exterior and interior—in which the spaces would be both independent and mutually reinforcing. That approach to space relies on the human capacity to assemble different registers of emotion into rich, polyphonic, and coherent experiences.

Island—with its relaxed curatorial grip and its emphasis on the ways in which people and places activate each other—is appropriate right now for several reasons. It fits into the theme of this Biennale, “Freespace,” which emphasizes what might be called architectural serendipity—the capacity of architecture to grant unexpected and often unintended spatial gifts as part of its active presence in the social fabric. More immediately, however, Island tacitly but transparently acknowledges the limitations of affirmative statements in the pavilion of a nation whose impending withdrawal from the European Union has placed it in a state of flux.

National uncertainty, and the many different kinds of uncertainty that have emerged recently in world affairs, makes Island particularly significant. The sight of the pavilion, festooned with scaffolding and identified above the door not merely as “British” but as “Great Britain” itself, has a trenchant wit: a nation under repair, with normal service to be resumed eventually. The fact that the Palace of Westminster is similarly graced with scaffolding as part of a massive refurbishment only adds to the mildly burlesque sense of disparity between architecture as exalted symbol and architecture as fallible matter. The meaning of scaffolding, however, depends primarily upon its relationship to the flow of time. Its presence might signify rectification of a flawed past, embellishment of a sound present, or anticipation of a viable future. Scaffolds signify change, and prompt questions about the implications of change.

In most circumstances, scaffolds are to be avoided. They mark out areas of hazard and exclusion. Island exploits this quality to convey at least a fleeting—and timely—impression that the British Pavilion is somehow out of bounds. Proximity reveals the scaffolding of Island to be inviting rather than forbidding: a means of greater public access to an open building. The staircase that leads to the roof-level platform is modular and obviously temporary, with hand-grips cut into the treads and plenty of visible joints. It nonetheless has breadth, flow, and a bolted-together grandeur that no purely utilitarian arrangement needs or possesses. The requirements of safe public access help to shift the vocabulary away from the specialized language of the construction site toward a general lexicon of contemporary architecture in which well-known buildings, such as the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, have complicated the relationships among systems, substructures, and surfaces.

That quick transition from one vocabulary to another exemplifies the way Island extends far beyond its immediate modification of space. The title alone, a single word, contains a densely packed set of connotations so rich that it is difficult to explain our world in metaphors without them. It is certainly difficult to imagine literature without them. Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611), in which an island is a place simultaneously of exile, rescue, and theatrical illusion, informed the project from an early stage. One might also cite another Jacobean work, John Donne’s Devotions upon Emergent Occasions (1624), which is today remembered for Meditation XVII and its supreme metaphor of common humanity—“No man is an island, entire of itself”—which carried political meaning in an era of fateful conflict between monarchy and parliament. John of Gaunt’s valediction in Shakespeare’s Richard II (1597) presents England as an impregnable “scepter’d isle . . . set in the silver sea,” shamefully diminished from within by misrule. For the British in particular, islands have long served as instructive reflections of their own condition. In Daniel Defoe’s novel of 1719, Robinson Crusoe builds a rudimentary emulation of British civilization. The shipwrecked schoolboys in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) descend into murderous, atavistic disorder. In fiction and sometimes in fact, islands are exceptions: magical, elusive, culturally or ecologically sui generis. An island might be Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), a place of exile and punishment, the center of the world, or the last place on earth.

Given time, an island can be many things. The rooftop platform that gives Island its name offers an unusually clear view of San Servolo, which lies in the Lagoon about a kilometer south of the British Pavilion. For nearly a thousand years, that islet was a place of spiritual and physical refuge for Benedictine monks who arrived in the eighth century, for nuns displaced by catastrophic flooding at Malamocco in the early twelfth century, and then for nuns fleeing the Cretan War in 1647. Later, San Servolo became a place of isolation and confinement, the site of an insane asylum from 1725 to 1978, when Italy closed all such institutions. That role lent San Servolo its unflattering nickname: the Island of the Mad. Today, it is home to Venice International University, a single campus involving a consortium of European, Asian, and American institutions. Islands can give sanctuary, enforce separation, stand in isolation, or serve as common ground in an interconnected world.

The rooftop platform was always intended to be generous: an airy, elevated piazzetta available for events and performances, with newly available views of the Giardini and the Lagoon. It is by far the most decorative aspect of Island, with plywood in three tones laid in a basketweave pattern. Seats, tables with umbrellas, and treetop foliage promise respite and retreat: a peaceful area where the hubbub of the Biennale recedes, and tea is served at four o’clock each afternoon from a trolley that Taylor designed for the purpose. This is a minor local tradition as well as a stereotypically British one. In the nineteenth century, before the building became the British Pavilion, it was a café. Jeremy Deller turned one room of the pavilion into a tea room as part of his exhibition English Magic (2013). A cup of tea taken in serenity above the fray is an appropriate gift for visitors who climb to the top. Whether the platform feels like a raft or a quarterdeck, precarious or supreme, is a question that remains deliberately open—and, in a city as vulnerable to the sea as is Venice, persistently relevant.

In contrast to the spatial and metaphorical expansiveness of the rooftop platform, the interior of the pavilion promotes introspection. It has been left untouched since Phyllida Barlow’s exhibition folly (2017) overwhelmed the building with an exuberant sculptural sprawl. Slight traces of that exhibition remain, dispelling any sense that the pavilion is a deliberately pristine blank space. In Island, the emptiness of the pavilion is reticence rather than amnesia. That quality is native to the site. During interludes between public exhibitions, the Giardini and its pavilions become quiescent: not abandoned, nor even deserted, but temporarily bereft because stripped of purpose. An open but empty pavilion preserves some of that atmosphere and makes it available for public use as raw material for a loose accumulation of impressions.

Some of those impressions might take emptiness as a sign of evacuation—an understandable notion in a city where buildings’ occupants often abandon flood-prone lower levels. That sense of flight bolsters the raftlike qualities of the rooftop platform, and also amplifies the notes of creative urgency that provisional architecture generates. Other associations put the pavilion in the company of works by contemporary artists who have used absence and traces of memory in order to address breaches in the social or historical fabric. All of these impressions tint Island separately and collectively.

The curators’ tactical withdrawal from the interior of the pavilion dismantles the conventional expository purposes of that space as effectively as wood and scaffolding create a new space. Exhibitions have physical and rhetorical contours that lead us along certain paths and toward certain thoughts. Island has instead two modes of being: one that expands toward the horizon with a compendium of metaphors, and another that thrives on interior silence punctuated by episodes of social interaction. Crucially, given the backdrop of impending transition for the country that commissioned it, Island presents those modes not as mutually exclusive but as complementary and permeable. It resists the oversimplification of atomized positions.

If Island has a natural ancestor in Venice, it is Aldo Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo (1979–80), a floating structure of wood and scaffolding that heralded the first Architecture Biennale. It is no longer extant, but it remains an indelible memory for many who saw it as it traveled from Venice to Dubrovnik, and a striking image for those who did not. Teatro del Mondo, which in title and construction referred to a long tradition of ephemeral architecture in Venetian festivals and carnivals, embodied Rossi’s understanding of theater and architecture as interdependent repositories of collective memory that are essential to a city. Island, like Teatro del Mondo, rests on the assumptions that our sense of past, present, and future—memory, action, and hope—are both built and performed, and that architecture can be backdrop, stage, and character simultaneously.

This, perhaps, is the most notable aspect of Island, an aspect that places it equally in the realms of art and architecture. The relationships between visitors and the spaces that constitute Island are comparable to the relationships that have animated advanced sculpture for at least fifty years. There is, above all, no such thing as neutral or inert space in Island, any more than there is inert space between viewers and Minimalist objects or their formal descendants. We might think of Island as a set of discrete physical spaces that viewers turn into integrated and expansive conceptual wholes. In order to do this, it uses the passage of time as effectively as it uses the control of space. It employs vocabularies of construction, impermanence, and dormancy not only to evoke a range of political and existential quandaries, including secession and climate change, but also to reveal the interconnectedness of tangible and intangible components in our encounters with the material world. Island demonstrates, to paraphrase Donne, that no place is an island, entire of itself. Utopia does not exist in isolation.

Images of British Pavilion © British Council