Drew Gilpin Faust is the Lincoln Professor of history and president of Harvard University. After growing up in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, she received a PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and was a member of the faculty there for twenty-five years. In 2001, she became the founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. She was named president in 2007.

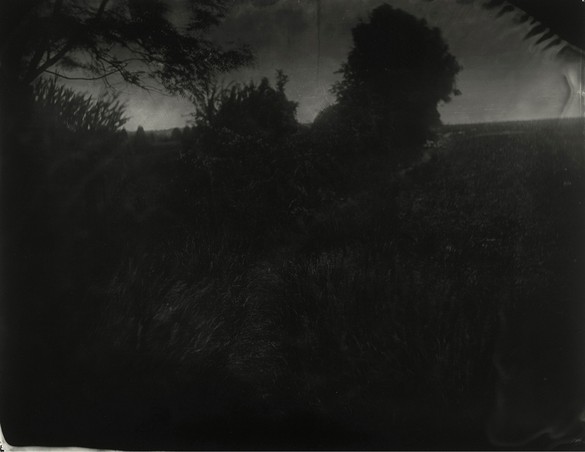

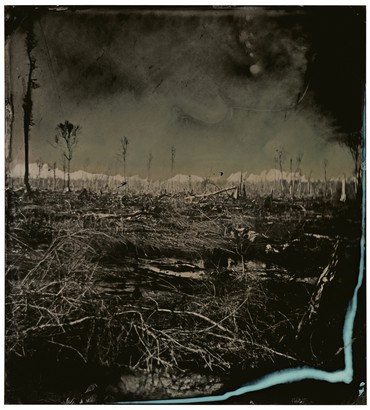

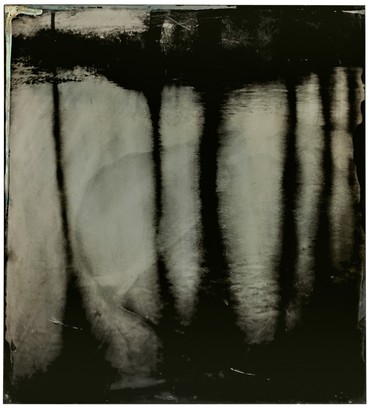

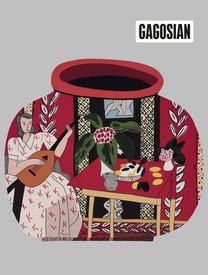

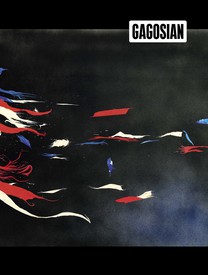

Sally Mann’s Antietam photographs picture no bodies. They are indistinct, scarred, cloudy. They are intended as works of art, not documentation. As one review of her 2004 show What Remains, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC., in 2004, explained, she “reports on nothing, she creates everything.” These photographs are reminders of what we cannot see. A shadowed stand of cornstalks at the left-hand side of one photograph invokes the savage, now legendary fighting that took place during the American Civil War, early on the day of battle in what has come to be known as the Cornfield. But the center of the frame is a shimmering cloud—of heat, of conflagration. In another photograph a dark line of trees seems studded with fairy lights—actually small imperfections in the emulsion that suggest a multitude of individual explosions erupting across the scene. In another, brightened hillocks of earth emerge as bulges out of the background gloom—likely the remains of defense works or burial mounds, but clearly a lingering claim that the war has imposed on the land. Antietam is, in Mann’s words, “exulted by—sculpted by death.”1

There can be few places more death-haunted than Antietam. At the end of the day on September 17, 1862, one soldier observed “hundreds of dead bodies lying in rows and piles,” while others were simply speechless: “words are inadequate to portray the scene.” The ferocity of battle had left both the Yankee and the Confederate armies staggering. Robert E. Lee limped south, leaving the field—and the dead of both sides—to the Union army. Its general, George McClellan, seemed paralyzed and failed to pursue Lee to take advantage of the victory, and this paralysis extended throughout the army as commanders and soldiers struggled to come to terms with the need to attend to the dead and wounded. In many cases, days went by before officers established burial details to dispose of the dead. A Union surgeon reported with dismay that a full week after the battle, “the dead were almost wholly unburied, and the stench arising from it was such as to breed a pestilence.”2

A New Yorker, Ephraim Brown, who had fought in the battle found himself ordered two days later to begin to bury Confederates right along the line where he had struggled so fiercely. He counted 264 bodies along a stretch of about fifty-five yards, each destined for a trench he was now required to dig. Origen Bingham of the 137th Pennsylvania did not take part in the fight, and when he arrived on the field four days after the battle, he discovered that most Union soldiers had been interred by their comrades. But he and his men were detailed to bury the hundreds of Confederates who still remained. Bingham secured permission from the provost marshal to purchase liquor for his men because he believed they would be able to carry out such orders only if they were drunk. Another Union burial party sought to make their task manageable by throwing fifty-eight Confederates down the well of a farmer who had fled before the arriving armies.3

Desperate families traveled by the hundreds to battlefields to search in person for kin. Frantic relatives crowded railroad stations in pursuit of information about husbands, brothers, fathers, and sons. Fearing his son dead after learning he had been wounded at Antietam—“shot through the neck thought not mortal”—the doctor and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., rushed from Boston to Maryland filled with both terror and hope. When after days of searching he at last located his son, it was as if the young captain had been raised from the dead: “Our son and brother was dead and is alive again, and was lost and is found.” But in the meantime Holmes had encountered parents far less fortunate than he, and had been horrified by his view of battle’s “carnival of death.” The maimed and wounded made “a pitiable sight,” he wrote, “truly pitiable, yet so vast, so far beyond the possibility of relief.”4

The makeshift nature of arrangements for dealing with the dead and wounded, the exhaustion of men called on for burial duty in the immediate aftermath of battle, and the frequent lack of adequate tools—even such basics as shovels or picks—often meant that graves were shallow and bodies were overlooked. When Lee marched north again in the summer of 1863, his soldiers were horrified to find hundreds of corpses still lying on top of the ground, prey for buzzards and rooting hogs. Death remained visible on Civil War battlefields long after the silencing of the guns. Sally Mann sees it still.

As they undertook the terrible work of burying both their comrades and enemies, soldiers found it deeply disturbing to be compelled to treat humans like themselves with such disrespect. To throw men into the ground like animals—with no coffin, likely not even a blanket to cover them; with no funeral rites; and more often than not, without even a name—dehumanized the living as well as the dead. The horror of the slaughter at Antietam, and the toll it imposed on the survivors as well as the slain, significantly contributed to changing national attitudes and policies about governmental responsibility toward the dead. By 1864, a group of eighteen northern states whose citizens had died at Antietam had joined together to purchase land for an official cemetery. In the years just following the war, 4,776 Union soldiers who had died in the battle and surrounding skirmishes were interred in what became the Antietam National Cemetery, where only 38 percent of the bodies were identified. The bodies of some 2,800 Confederates were gathered in three burial grounds nearby.

The Civil War changed many aspects of American life—eliminating slavery, establishing a powerful new nation state, creating hundreds of thousands of grieving widows and orphans. But at the heart of its transformations were new understandings of death and dramatically altered assumptions about the obligations of the nation to citizens who had died in its defense. The attitudes of the Civil War era seem today unimaginable. The United States is now committed to identifying every soldier lost in battle, returning them to their families, and honoring their sacrifice. The Department of Defense spends more than $100 million every year in the continuing effort to locate and identify approximately 88,000 individuals still missing from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. These commitments and policies grew out of the mass casualties of the Civil War. Those deaths have exerted their powerful impact on the present, just as the bodies of the slain have made a lasting imprint on the soil where they fell, infusing those fields with the spirits and sacred meaning Mann’s photographs seek to capture.5

The cruelties of Civil War death assaulted fundamental assumptions about what it means to be human as well as essential beliefs about how to die. Americans of the mid-nineteenth century had a clear understanding of what constituted a “Good Death,” and these expectations were directly challenged by the circumstances of war. Perhaps most distressing was the fact that thousands of young men were dying away from home, distant from family and friends who could record their last words and scrutinize their last moments for evidence of their eternal destiny—of whether they were prepared to die, were at peace with their fate, confident in their faith, and prepared for the world beyond. Such a departure from life could reassure a family that they could anticipate being reunited with their lost loved one in eternity. Readiness for death was critical both to the moment of passing and to life everlasting. All should keep death ever in their consciousness and be prepared for its appearance.

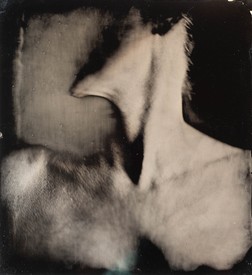

Much has been written about the very different posture toward death of today’s Americans. Rather than living with an acute awareness of death’s proximity, American society has repressed and denied it, in personal and family life, in religion, and in funereal and medical practices. But Mann has a decidedly different sensibility—one more like that of her forbears in the nineteenth century than inhabitants of her own time. Like Americans a century or more ago, Mann believes that only by looking death in the face can we fully comprehend and relish its opposite. A good life is one undertaken in full view of its end. Loss, she has said, “is designed to be the catalyst for more intense appreciation of the here and now.”6

Photography is a remarkable instrument for such appreciation. It has a special relationship with death. It captures, steals, stills time; it renders the impermanent permanent; it transforms a moment into meaning. It has the capacity to exert a kind of control by defining and framing what is otherwise incoherent and formless. It compels us to look, to see both absence and presence, and to strive to understand how each constitutes the other. Yet in appreciating the here and now, Mann also requires us to acknowledge its inseparability from what has come before and what will persist after us, its inseparability from history and from the inevitability of our own deaths.7

These themes are in one sense abstract, universal, philosophical, but Mann situates them within the context of a particular place and a particular moral narrative—that of the South of slavery and war, with their revelation of the capacity for cruelty and inhumanity, the “sediment of misery” that this history has imposed on the land. Mann’s is a South that must remember its past clearly in order to struggle beyond it. She knows that this work is not complete. As I write, in August 2017, Charlottesville, just seventy miles east of Lexington, has erupted in devastating racial violence sparked by white supremacists protesting the planned removal of a statue of Lee. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” wrote William Faulkner, in a line quoted so often because we see again and again that it is so very true. We as a people and a nation, as Southerners, as Virginians, are still struggling with the meaning of the Civil War and its legacy, still striving to realize the “new birth of freedom” that Abraham Lincoln insisted must be the justification for the war’s slaughter, still seeking to overcome the history of racial injustice that has so deeply defined us. Mann’s photographs are a part of that struggle, exhorting us not to look away but to confront that past, to embrace our mortality, and to live deliberately and humanely in the face of the truths we have tried so long to deny.

1Henry Allen, “The Way of All Flesh,” Washington Post, June 13, 2004, and Sally Mann, on Charlie Rose, PBS, November 12, 2003.

2James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 6, and Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), p. 66.

3Faust, This Republic of Suffering, pp. 67–69.

4Oliver Wendell Holmes, “My Hunt after ‘The Captain,’” Atlantic Monthly 10 (December 1862): 764.

5See Caroline Alexander, “Letter from Vietnam: Across the River Styx,” The New Yorker, October 25, 2005, p. 44.

6Mann, quoted in Ann Hornaday, “‘Remains’ to Be Seen,” Washington Post, June 6, 2004. On the denial of death see Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), and Atul Gawande, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, 2014).

7Mann, quoted in Hornaday, “‘Remains’ to Be Seen,” and William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1951), p. 92.

Artwork © Sally Mann. Excerpted from an essay by Drew Gilpin Faust, first published in Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, produced by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and published in association with Abrams. The exhibition, co-organized by the National Gallery of Art and Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, is on view from March 4 to May 28 in Washington and from June 30 to September 23 in Salem. It also travels to Los Angeles, Houston, Paris, and Atlanta, closing in January 2020.