Dan Duray is a writer, reporter, and editor whose work has appeared in The Economist, The New York Observer, The San Francisco Chronicle, Billboard, Artnews, and The Art Newspaper, as well as on the websites for New York magazine, Bookforum, Vanity Fair, Vice, Bomb, The Guardian, and T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

Art viewing does not come naturally to the human animal—we need to be coaxed into stopping, looking, thinking. In the past decade, museums and galleries around the world have remodeled and rebranded to make visitors feel more welcome. Step inside please, the buildings seem to say—we won’t bite, and moreover we’re LEED-certified.

The opposite is true of art-storage facilities: every aspect of them reminds you that art is also a commodity. Identification is demanded, doors are locked behind you, and someone is always following close behind.

It was in these circumstances that I saw the latest pieces by Walton Ford. We were shuttled through a warehouse of crate-stacked halls like the one at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, finally reaching a simulacral conference room in the center. The nineteenth-century ornithologist John James Audubon’s to-scale portraits of American birds are a recurring touchstone for Ford, whose watercolors accordingly always feel like artifacts of an earlier time, whether at The Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, or the Smithsonian. But his works have never felt more rarefied to me than they did in these conditions. They were big secrets finally revealed, leaning against a wall. When Walton Ford starts showing you giant griffins, you start to wonder if he might not have actually found some.

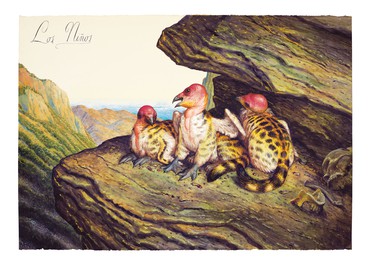

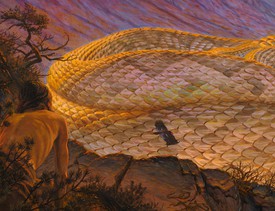

“This show has been a big breakthrough in that way,” Ford said at his TriBeCa studio, where he and he alone creates his works. “As a general rule, I rather loathe the whole fantasy thing. I don’t have a great urge to paint fantasy animals. It’s pretty corny. Mine will never be as cool as the Game of Thrones dragons.” But the new work, Ford’s first significant foray into the subject matter of California, explores an early creation myth for the state that required him to picture griffins. To create these imaginary creatures he merged California mountain lions with California condors—he wanted to create a New World griffin, as opposed to the classical depictions that borrow from Mediterranean or African wildlife. This amalgam actually goes a long way toward verisimilitude, since the animals’ wings, beaks, and haunches were shaped by Californian natural selection.

But it’s the interior life of Ford’s animals that makes his images—they don’t just look real, they seem to move and emote. If he simply drew a bird’s head on a lion’s body, it wouldn’t look natural, you wouldn’t be able to see it in your head. “The way that I actually solved that problem was that you have to decide you’re going to pick one of the animals to emphasize. In my case, I emphasized the feline qualities,” he told me, pointing out that his alighting griffin lands like a cat jumping off a kitchen counter, and that “even though they’re bird claws, they’re resting in a lionlike way.”

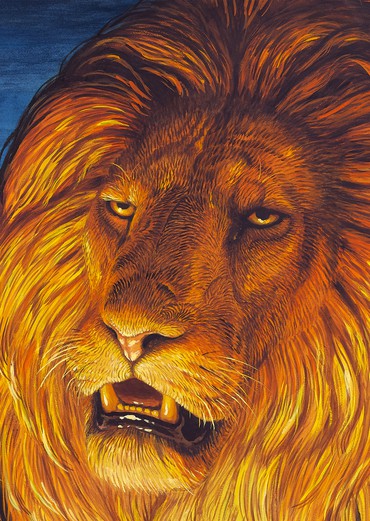

“When the popular press writes about me, they love to take a natural-history figure like Audubon and then add a pharmaceutical to it,” Ford added. “They say, ‘Like Audubon on Viagra,’ or ‘Roger Tory Peterson on Ecstasy.’ That’s become a thing. They’re not really wrong.” While it’s right to praise the creativity and craftsmanship of Ford’s execution, though, such appraisals miss his work’s conceptual underpinning, the self-made rules that he has followed since the beginning of his career. It is not merely that his pictures are almost always invented studies of animals. As with Audubon, Ford’s animals are always life sized, and are rendered in watercolor in scientifically accurate detail. As a rule, though, they go on to do things they wouldn’t do in nature: the ape got drunk at dinner and is making a fool of itself. The lions are that melodramatic couple you know, always breaking up and getting back together. The Cuban red macaws represent the legacy of José Martí.

Add to these rules too the fact that, while being eerily accurate, these animals also cannot look too real. “When I was a young kid looking at Audubons, I wanted one,” Ford said,

I wanted one of my own. I thought, “What a cool thing to have.” Then later, that evolved. I would see Bruegel’s The Harvesters painting and want that. I just started doing knockoffs. It was like I didn’t want to forge the things but I wanted to own them. Then I thought if I could do them, I could add my own sensibility, which was informed by underground comics and horror films and Frank Frazetta and all kinds of tacky shit that I grew up with that I loved. My teenage-boy aesthetic mixed with this very gun-room, conservative, Republican-looking art.

Which is to say that the “David Allen Sibley on poppers” tag underrates Ford’s postmodern elements of pastiche and collage. His animals are so good at being uncanny because they’re dramatized, or anthropomorphized, not from nature but from a Platonic form known to all of us. “I’m more interested in animals in the human imagination,” he said, “than in animals as they appear in nature.”

(Personality wise, it should be said, Ford is hardly the type to camp out for days in a blind in the Serengeti, like a Planet Earth cameraman. “When you go into nature, animals are sitting around,” he told me. “They’re trying to either get calories or not burn too many, so they loaf around a lot. That’s why the zoo is always a big letdown. It’s like: ‘Where is it? What’s—is that it, in the fucking log?’ ‘Yeah, you see that little thing? That’s its tail sticking out.’ Like, great.” He rolled his eyes.)

It’s a sort of attraction-repulsion thing, beautiful to begin with until you notice that some sort of horrible violence is about to happen, or is in the middle of happening

Walton Ford

As such, Ford’s TriBeCa studio is not what you might imagine. Less menagerie than library, it contains only a few animal models, though there are walls and walls of books, from the classics to the intellectual to the pulpy: Audubon’s journals, and biographies of him. Eros in La Belle Epoque. Eleven copies of Moby-Dick. Blondie Iscariot, Siren of the Underworld.

The origins of this show, Ford’s first with Gagosian, lie in a book: the Spanish novel The Adventures of Esplandián, by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, published in 1510. Ford likens it to one of the chivalric books that are burned in Cervantes’s novel Don Quixote (1605–15). “Know,” Montalvo writes, “that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.” This was enough to encourage the Spanish conquistadors in the New World to seek such an island, and when Francisco de Ulloa discovered the Baja Peninsula, in 1539, he decided to name it “California” after this passage. Ford, then, has mined a fiction to address a state whose chief export is fiction. “The deal,” Ford said, “is that when men would fetch up on the shores of California, this Amazonian tribe would kill them by feeding them to griffins, which were raised as a flock of fighting beasts to wage war on all mankind.”

Ford has an East Coast sensibility; he’s as well read and wisecracking as you may have guessed from his pictures. For most of his career he painted in a barn in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, among the longest-colonized parts of the United States, where nature has been thoroughly categorized and subdued. But his work, of course, thrives on the irony of trying to categorize nature in a scientific way, or even an artistic one. His work is marked by the disruption of this mannered ethos—by chaos, by emotion, or by the sublime. For the largest work in the show, then, La Brea (2016), he has probed a similar if better-known dichotomy: the sinister underside of Los Angeles’s glamour. In this image, all the natural beauty that has been devoured by the La Brea tar pits over the eons returns to feast upon those who have lived too well around it. Camels, buffalo, and dire wolves roam the flaming grid.

Ford’s paintings usually come with little throwaway jokes—the skull tucked away near his baby griffins, or the griffin electrocuting itself in the background of the otherwise majestic work Isla de California (2017). In La Brea that wit is seen in the presence of the Chemosphere, the distinctive house built by the architect John Lautner in the Hollywood Hills, today owned by Ford’s friend the publisher Benedikt Taschen. Here it is rendered empty, hovering over this zoological Helter Skelter.

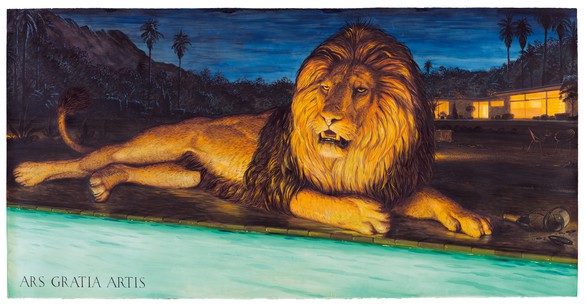

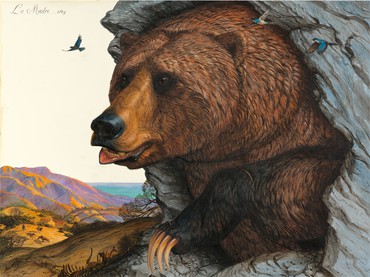

Ford’s first instinct for this show was to do something on Hollywood’s animals, like those in the private zoo once called Goebel’s Lion Farm, where the actress Jayne Mansfield’s six-year-old son was once attacked by a lion during a visit there. (This idea is transformed in Ars Gratia Artis [2017], in which Ford depicts the MGM lion doing a Sunset Boulevard kind of thing, lounging by the pool, drunk and forgotten.) As I was writing this he texted me the sketch for a forthcoming work, La Madre, in which a “freak giant grizzly—emerging from a cave” takes up two thirds of the panel. Around the end of the nineteenth century, he told me, well before California adopted its current, bear-logo flag, it had a bear problem: leather traders were leaving piles of cow carcasses that attracted bears. Vaqueros would hunt the bears with lariats, pulling them apart, or pitting them against bulls. By now you can probably see the Walton Ford painting in that, no?

This show taps into a rich vein for the artist, to put it mildly. “When I go to LA, I get the creeps about the earthquake, the Big One,” Ford said. “About the fact that even the ground you’re standing on can rise up and kill you. It really is real and people know it. It’s fucking inevitable! I actually legitimately get the willies when I’m there. I could picture myself losing it in LA, like in Mulholland Drive.”

Artwork © Walton Ford