Philip Tinari is the director of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, one of China’s leading institutions of contemporary art. From 2009 to 2012 he founded and edited LEAP, the first internationally distributed, bilingual contemporary art magazine in China. He was cocurator of the 2017 exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Photo: Stefen Chow, courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

HAO LIANGI am always playing on and playing up the strengths of traditional Chinese painting in my work. But I am also looking at film, literature, and art, and using this foundation to break some of the limits of ancient painting. The field of ancient painting is relatively fixed, so it can be hard to find a way in. One needs to comprehend by analogy.

PHILIP TINARIHow do you approach the question of temporality in your work, and in Chinese painting more generally? A lot has been written about the differences between Chinese and Western painting in terms of their relationship to time.

HLIt’s complicated. In Chinese painting, time tends to be mutable, hard to characterize, and a bit different in each work. Chinese painting tends not to care about the decisive moment, although its temporality also remains fundamentally linear. Occasionally there appears a work that conveys a more complex understanding of time. I work in the present tense, and I try to exaggerate this complexity, enlarge the stranger perspectives, deliberately create a sense of mystery.

PTYour 2015 scroll The Virtuous Being is a great example of what you are talking about. It’s almost like a mise en abyme, with levels upon levels of references.

HLIt moves in circles, with a linear historical narrative that connects back to itself, and then breaks itself up. I was thinking about how to draw connections between different times and places. This work began from some reading I was doing—I came across a man called Wang Shizhen (王世貞, 1526–1590), one of the most famous art critics, poets, historians, politicians, and collectors of the late Ming. He was a point of connection among many different facets and individuals of the art world in China at the time.

In my study of traditional ink and wash paintings, my view of time and space staggers and jumps.

Hao Liang

PTA bit like Guillaume Apollinaire at the turn of the twentieth century.

HLYes, a lot like that. Wang was a very complex person. He built a strange garden called Yanshanyuan (弇山园). And even more strangely, he opened it up to the locals.

I felt like this was similar to what happened after 1949 with the construction of People’s Parks in cities around China. And I hadn’t anticipated that this garden was actually not destroyed in the Revolution, but rather eroded by time, disappearing bit by bit until by the early 1950s it had entirely vanished. It was then rebuilt in the 1990s by the local government, but as a tourist attraction, and there was nothing the scholars and historians, who would have preferred a more faithful or sensitive re-creation, could do. The local officials even added a Ferris wheel, which appears at the end of my scroll.

I was suddenly struck by the connections between different historical moments, by resemblances across the centuries. This makes it harder to critique what is happening in the present; one starts to doubt the value system behind cultural preservation.

If we go back in history, we find that the kind of openness implemented by the local government was very much in keeping with what Wang Shizhen himself wanted. And this suddenly gave me a new way of thinking about the connections between different moments in Chinese history. My outlook had previously been fixated on the various ruptures Chinese culture has undergone—the New Culture Movement, Liberation, and so on—but once I had researched this garden, I felt a new possibility for escaping the limitations of history, and a new hope for connections between the ancient and the modern.

PTSo it’s a kind of recovery, and a kind of optimism? Because people get so fixated on the idea of what has been destroyed or lost.

HLI find this notion of displaced connection to be somewhat romantic, even. Because Wang Shizhen was himself working to recover certain ideas about humanity and nature that had been imagined by the poet Wang Wei (王维, 699–759) centuries before him. All of these ideas were connected, and that is what makes this work interesting. For me it was a way of raising the stakes. How could I research a specific question, and, through artistic expression, give it an appropriate form? Once I finished this work my whole view of history had been changed, to be much more disordered. This sense of disorder became pronounced in the works I did for my solo show at UCCA (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art), Eight Views of Xiaoxiang (2016).

PTI suppose that suite of eight works was your largest single project or cycle of paintings to date.

HLAnd the one that has consumed more time than any other! I spent nearly three years on those paintings. In making them, I was hoping to solve problems not only through research; I wanted to use visual means to address contemporary issues. I was most interested in the question of the contemporaneity of Chinese painting, and in the research behind this question. I was also trying to respond to art history, and to integrate some of my previous work.

PTAnd you were working within an established framework—many artists over the centuries have made their own attempts at the “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang.” It is something of a mother subject, almost like the various scenes of Christian religious painting. For you, each individual work was quite different. Some are based on a single story, or a single perspective. Each one turns on a slightly different device.

HLYes, I was looking to approach this overarching subject of the “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” from a variety of perspectives. As I looked at the canon of works around this subject, I discovered it is actually not just a Chinese subject, but an East Asian one—Japanese and Korean artists have also worked on it. And until now, most artists have looked at it as an aesthetic question. So this subject provided a constant source of nourishment for me—it was incredible because I could just go deeper and deeper into thinking about it, and never stop exploring.

PTCould you describe this process of discovery in a bit more detail? From your reading and research, through the conceptual exploration, and on to the creation of the work itself, it sounds like a complex process.

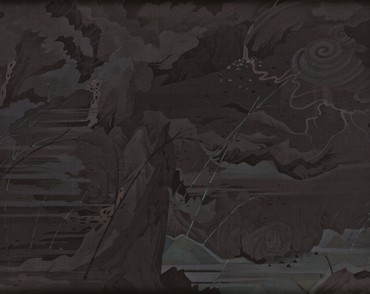

HLI’ll speak about one of the works in the series, Scholar’s Traveling (2016). Because I wanted to understand the history and the geographical discourse around Xiaoxiang, I read the works of the Ming scholar and traveler Xu Xiake (徐霞客, 1587–1641), which describe his experiences in the region. After reading them I realized that he was actually writing about the agitated sentiment of the independent individual in relation to homeland and to the imperium. And he was doing it in a way that a more traditional intellectual might not have. Before Xu’s time, only the emperor had the prerogative to undertake such a large-scale journey, on the thinking that all-under-heaven [tianxia, 天下] belonged to him alone. But the modern awakening of the late Ming brought with it a transformation: an ordinary man was doing what previously only the emperor could. A historical transformation like this makes you think. Later, as I was making this image, I researched what kinds of landscapes the emperors preferred, and so this composition refers to Wang Ximeng’s (王希孟, 1096–1119) A Thousand Li of Mountains and Rivers (千里江山图, 1113). This painting, which was recently exhibited at the Palace Museum in Beijing, is a political painting: thousands of miles of landscape, rendered like a sandbox. It is a landscape as seen by the emperor, for the pleasure of the emperor.

PTNot unlike Michel Foucault’s idea of the panopticon.

HLI intentionally chose to paint it from the perspective of the emperor. But in fact, I was making a painting about the travels of a scholar, so I then tried to distill and incorporate his various stories, but without their plots, because those would be too difficult to render on a single picture plane. I focused instead on the feeling that each of these stories left me with, or specific images from them. For example, Xu writes of being on a mountaintop and seeing flames engulfing a mountainside, going up into the sky, lighting up the stars—fire that was like rain. I incorporated this image and many like it into my landscape. And this was actually one of the simpler and more straightforward of the paintings. Others in this cycle were more in the vein of The Virtuous Being, involving preliminary research, site visits, and other kinds of preparation.

PTA lot of the writing about Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–23) talks about how he saw the different components of that work in a highly allegorical way, and how his process of composition was largely about moving the elements around, refining them. It was a process of making conceptual elements into a visual narrative, a process that seems somewhat similar to what you describe.

HL[Marcel Duchamp, la peinture, meme (2014) at Centre Pompidou] showed his notes for the Large Glass, as well as other documents surrounding it. It left me with the idea that preliminary notes and documents can inform the visual shape that an artwork ultimately assumes, and that this visual form is not a dry image. Duchamp chose to use glass, which gave his final composition another valence, a new kind of poetry as the light shines through. Chan Buddhism emphasizes fluidity—the idea of being and nonbeing at once. That is the kind of visuality that interests me. The simply diagrammatic can never capture a concept. And so I polish and refine.

PTDid your understanding of your own work or working methods change at all after the UCCA exhibition?

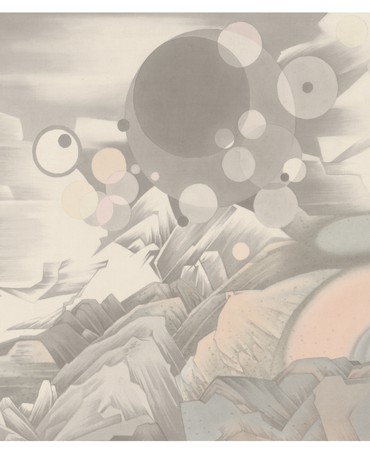

HLThat exhibition, more than anything I had done previously, emphasized the conceptual nature of my painting, as well as the specificity and completeness of my painterly language. The research and study took a back seat. In this new scroll Streams and Mountains without End (2017), I am trying to work out the connections between the theories of Dong Qichang (董其昌, 1555–1636) and Wassily Kandinsky, to put together these two sets of ideas about art separated by three centuries. I decided not to try and explain the similarities and differences between them, but to construct a vista that might be able to contain these two thinkers’ characterizations and longings. In the end this vista might feel like a pine tree with a vine wrapped around it. That is what I am going for, a landscape that very directly refers to a set of theoretical texts. When I was working out the relationship between the small portraits and the landscapes in this work, I was influenced by Dong Qichang’s idea that paintings should see the large through the small. Painting the landscapes, I tried to organize the space around the human body, to change the space; and painting the people, I was thinking of how to render them almost like stones. A pure and adventurous painting practice is built on a string of ideas like this.

PTYou have done all this research on the conversations that artists and critics have had with one another—in the time of Wang Shizhen, or during the Republican period, for example. But what about the artistic environment, the theoretical conversation, in which you find yourself? I don’t mean in terms of institutions or the market. Rather, what do you perceive as the urgent questions that the artists you find yourself in dialogue with are struggling with?

HLI have thought a lot about this, and these questions drive some of my work. I feel like the narrative around Chinese contemporary art has been overly simplified.

There is a stock history that begins with the ‘85 New Wave, and moves through the 1989 China/Avant-Garde exhibition up to the present.1 This sort of phenomenon-driven approach to contemporary art fails to consider the complexity of Chinese society. How did Chinese culture evolve from the modern into the contemporary? After the New Culture movement, what is the relationship of the present with the ancient past? The anxious relationship between ancient and modern simply gets deferred onto the contemporary. I want to disrupt these connections, or to build new ones. I hope that I can structure a more complicated narrative of the relationship between old and new.

PTAnd do you feel like the artists around you are also thinking about this?

HLI do. Artists like Yang Fudong (楊福東, 1971–), Duan Jianyu (段建宇, 1970–), Liang Yuanwei (梁遠葦, 1977–), Xu Lei (徐累, 1963–), Liu Ye (劉野, 1964–), Wang Yin (王音, 1964–), and Wang Xingwei (王興偉, 1969–)—we all do very different things, to each his or her own, but I believe we all think about these questions. Previously when people spoke about contemporary art in China, they would begin from the ‘85 New Wave, but now this seems arbitrary. Think about the visual culture of the Cultural Revolution, and its huge influence on the art that emerged in the 1980s and into the 1990s. But where did Cultural Revolution imagery come from? There was the influence of the Soviet Union, but also of the films made in Shanghai before 1949. How can we complicate this narrative of contemporary art in China? Certainly not by drawing comparisons with Western analogues and precedents—it is not the case that whatever happens in the West, there should be a Chinese equivalent. There should be a different narrative system. Chinese artists, young and old, are perhaps all considering this question.

PTSo that is how you would characterize the situation of artists in China today.

HLWe want to break through time and space. The situation today is like that of Sun Wukong (孫悟空), who appeared from a crack between some rocks.2 As soon as he appeared he had to go find the Jade Emperor, and to struggle against the heavens until he was put down by Buddha. Then he went west to bring back the scriptures, which allowed him to finally figure out where he had come from. This might be a good metaphor for Chinese contemporary art. We still need to understand where our modernity came from, to construct our own subjectivity, and our own art system. The government certainly isn’t going to do that for us; if anything, it will undermine us. We depend on the vibrancy of the nongovernmental cultural establishment for our energy.

1The exhibition took place at National Art Gallery, Beijing, in 1989.

2The monkey hero of Wu Cheng’en’s (吴承恩, 1505–1580) novel Journey to the West (c. 1592).

Artwork © Hao Liang; photos: courtesy Hao Liang Studio

The full interview with the artist appears in the exhibition catalogue Hao Liang: Portraits and Wonders available through the Gagosian Shop