Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

Jed Perl was the art critic for The New Republic for twenty years and a contributing editor to Vogue for a decade. He is currently a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books. Among his many books are Calder: The Conquest of Time, Magicians and Charlatans, Antoine’s Alphabet, New Art City, and Paris Without End. He has written for Harper’s, The New Criterion, The Yale Review, Salmagundi, and many other publications. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and teaches at the New School in New York. Photo: Duane Michals

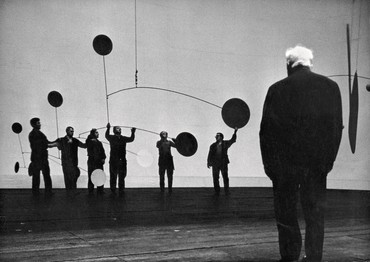

Alexander S. C. Rower is founder and president of the Calder Foundation. Since 1987, Rower has documented more than 22,000 works by Calder and established an extensive archive dedicated to all aspects of the artist’s career. He has curated and collaborated on over 100 Calder exhibitions worldwide.

Wyatt AllgeierHow did this project come about? I’m curious about the backstory.

Jed PerlI’ve always thought that if I ever wrote a biography, Calder would be the one. Calder embraced many different worlds; that makes him a great biographical subject. For half a century—from the 1920s to the 1970s—he was an essential figure in both the Parisian art world and the New York art world. There’s hardly any other artist about whom that can be said. He was a key figure in the international avant-garde, but unlike so many avant-garde artists, he knew how to give his most daring ideas a broad, heterogeneous appeal. He was a pathfinder, bringing modernism into the mainstream without diluting modernism’s primal power. Honestly, I’d always assumed, given there hadn’t ever been a biography, that either somebody had been working on one for thirty years or somebody was preventing it from happening. And then I crossed paths with Sandy and—

Alexander S. C. RowerYou discovered there was somebody preventing it from happening [laughter].

JpBeing as you’re the somebody, you can tell that part of the story.

ASCrIt’s a funny thing. Jed’s a writer, and I couldn’t just let some schlemiel—that’s American—go ahead and write a biography. As you can imagine, I had so many different people proposing half-baked ideas for a biography. This one illustrious writer came to me and said “I want to do the Calder biography.” I asked, “Well, why now?” And she said, “There’s a Calder show opening in eighteen months, and I’ve gotta bump this book out.”

So when Jed came along, we didn’t know each other at all. I had read some of his criticism and he had heard some criticism about me [laughter]. It was an amusing time. Jed had been invited to write a brief book about Calder, and he asked to see me and we had our first séance together. I asked him why write that basic book when he could write the biography? And he said “What?!!” What he didn’t know was that I had recently reread an amazing article he wrote in 1998—it was the time of the Calder centennial show at the National Gallery—about Calder, [Fernand] Léger, and [Alvar] Aalto. He went away, and a few days later he said, “Well, let’s give it a shot.”

JPAt the same time as there was this Calder centennial retrospective in Washington, there were retrospectives dedicated to Aalto and Léger at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. When I was the art critic at The New Republic, I often put a number of exhibitions together in a single essay, and those seemed to go together very well. When I started reading in preparation for the piece, I discovered that these three were close friends. So I wrote an essay called “Being Geniuses Together,” and then Sandy, when I saw him almost a decade later, said, “How did you know all of this stuff without coming here to do research?” I said, I went to the library [laughs].

ASCrOften people walk in our door completely unprepared. First, they’ve not done any research, so they don’t really know much about Calder because Calder is actually a very opaque artist. It’s hard to get to the core of what he’s about because there’s this frilly stuff in front—there’s motion and “dancing shapes” and colors—and it takes you completely away from Calder’s intent, from what he’s trying to communicate. So when you find somebody who’s already got a foothold on who Calder is and what he was about, it’s a rare thing and you latch onto him.

WAJed, since this is your first biography, I’m curious to hear about your strategy. There is much debate among writers working in the genre about the best approach. How did you dive into such a monumental task?

JPThere are plenty of biographies I admire enormously. One thing I always say about writing is that people get very balkanized about defending boundaries: there’s art criticism, dance criticism, movie criticism; there are art biographies, biographies of writers, etc. I don’t see it that way. I see writing, whether biography or criticism, in a broader frame. And some of the biographies that have meant the most to me are literary biographies—the great biography of Henry James by Leon Edel; Richard Ellmann’s biography of James Joyce; Ellmann’s second, major biography, of Oscar Wilde—these are extraordinary books. I’ve always loved these books, and they were especially important for me as I embarked on my biography of Calder. As for biographies of artists published in recent years, John Richardson’s A Life of Picasso is the one I turn to. It’s an extraordinary achievement.

Some biographers focus so much on the life that the artist’s work just kind of gets tossed in—sometimes almost tossed aside. I wanted this to be a book about Calder’s emotional life, his mental and psychological life, but also about his imaginative life. So you’ll find that I move back and forth between different sides of the art and the life; after a chapter focused on Calder’s family and friends there will probably be a chapter that’s more driven by the work itself. I really enjoy taking some deep dives into issues raised by the work, whether the relationship between the Cirque Calder [1926–31] and the history and philosophy of puppetry, or the relationship between the development of the mobile and ideas about the fourth dimension. I was determined to write a book that had an overall narrative drive but that also moved and shifted in different directions at different times. Sometimes what I’m writing is close to pure criticism; at other times I’m just telling great stories. I don’t think that anybody can fail to be moved by the story of how Calder met and fell in love with Louisa James, on a boat returning from France to the United States.

A biographer has to tailor his approach to the artist he’s writing about. Richard Ellmann is interesting in that way. His biographies of Joyce and Wilde are very different; he shapes the story in a way that reflects the subject. Joyce was something of a loner, so the book tends to focus on his family and a few friends. Wilde was anything but a loner, so Ellmann greatly expands the social canvas. With Calder, one of the exciting things to write about is his many friendships. I had the opportunity to write about Marcel Duchamp, but also about Mary Reynolds, an extraordinary woman who introduced Calder to Duchamp and was probably the great love of Duchamp’s life. Reynolds was herself something of an artist; she created enchanting bookbindings. And although she was an American citizen, she lived in France in the early years of the German Occupation and was a hero of the French Resistance. Calder’s friendships are very much a reflection of who he was—of the way he reached out in different directions and engaged with so many aspects of the world.

ASCRIt’s not a typical biography, the way that it reads, because you’re also explaining the times.

JPI think you have to when you’re dealing with an imagination as great—as voracious—as Calder’s. Genius is a mysterious thing, it works in ways that our minds, even really smart people’s minds, don’t work. There are connections that geniuses make between everything that’s going on around them; it may be that even the geniuses themselves aren’t fully conscious of what they’re drawing together. Calder was like that. Only by taking a very broad approach can a biographer begin to suggest all the forces that were impacting a great artist’s imagination—that were surrounding him, enveloping him.

WAYou want to reveal part of the matrix around him.

JPRight. But it’s got to be built in a way that’s both big and light; you don’t want to push too hard, you don’t want to overstate things, which is—

ASCRA big challenge.

JPYes.

ASCRBecause there’s so much nonsense you have to scrape away to begin with.

JPThere are also hidden stories. In the 1950s and ’60s, for instance, Calder had a continuing impact on the avant-garde. His abandonment of the pedestal, for example, had a bigger impact on artists like George Sugarman, Mark di Suvero, and David Smith than has ever been acknowledged. I think the Minimalists looked more closely at Calder’s work than they would sometimes let on. And the relationship with the Abstract Expressionists is really interesting—

ASCRCalder’s relationship to gesture in the mid-1950s is extraordinary, and very little is known about it now. At the time it was a hot subject.

WAOne of the most interesting threads that you go into in the first volume is theater. You explore the changes in theories and practices, from Picasso and Jean Cocteau’s Parade with Erik Satie [1916–17], to Frederick Kiesler and beyond, in relation to Calder’s Cirque. I don’t really see this happening as much anymore, the art world and artists engaging with theater in such a concerted way.

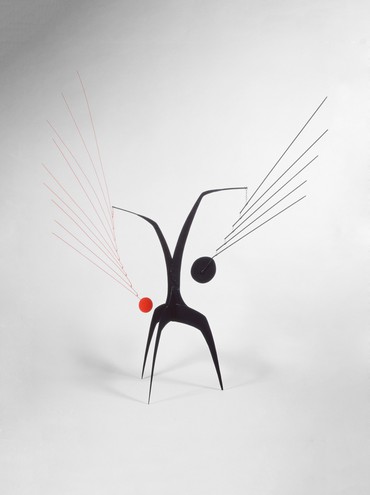

JPWell, Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes was a critical force in European art for twenty years, from 1909 to Diaghilev’s death, in 1929. In the book I quote Virgil Thomson, who suggested that Diaghilev’s death might have been a more significant loss for the arts than the economic deep freeze that came with the Depression. There were all these creative people in Paris; and then you had Diaghilev, who had embraced the Wagnerian idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk and inspired so many extraordinary experiments, both directly and indirectly. And Calder, arriving in Paris in 1926, felt the tremendous idealism and optimism of this union of the arts. He began with the Cirque, which Cocteau was one of the first people to see. Ideas about theater and theatricality shaped Calder’s work from then on. He rarely if ever turned down an opportunity to work in the theater; in the 1930s he collaborated with Martha Graham and, with Thomson, on a great production of Erik Satie’s Socrate, a work for voice and small orchestra. But the impact of the theater is more general; one can certainly make the argument that a mobile is a kind of theater.

The connection with theater flares up again in the late ’60s and early ’70s. There will be an entire chapter in volume two dedicated to the revelatory nineteen-minute ballet without dancers, Work in Progress, that Calder created at the Rome opera house in 1968. In that ecstatic, optimistic moment in the 1960s, there’s a return to the ambitions that had shaped Diaghilev’s dream of the Gesamtkunstwerk.

WAAnother of the running threads that I thought was really intriguing was the recurrence of animals. There’s Duck and Dog, both from 1909, very early in Calder’s childhood. And there are references to animals in form or title onward throughout his adult life. In modernism there’s always this interest in animals, and the directness of their emotional availability.

JP Exactly. Which goes back to the Romantics.

WARight. But beyond that, animals are a common trope in children’s toys. You return to Baudelaire’s essay “The Philosophy of Toys” [1853] multiple times—

ASCRWell, first of all, Dog and Duck aren’t toys. They’re sculpture. He made them for his parents for Christmas. There are a lot of misconceptions because Calder mixed up everything, he brought all these lines together, blurring boundaries. So what’s the difference between a production wooden toy—a kangaroo that hops up and down as you pull it on a string for a child, which Calder designed for Gould Manufacturing in Oshkosh in 1927—and a wire sculpture of a kangaroo, which also hops on its wire feet but is a unique work, not a thing for mass production but a humorist sculpture? Back then, humor was a high art form and the exploration of humor as a high art form was taken seriously. It was something that interested Duchamp very much, for example. So the fact that Calder made two kangaroos, one definitely not for children and one literally for children—but still a high art form, challenging definitions—we get mixed up today about what it all means. It’s been a goal of the Calder Foundation to pull it all apart and show: this is a sculpture, this is a child’s toy, this is an adult toy—and what is the deeper meaning?

JPOne of the great things that Sandy and the Foundation have done is exactly that, scraping away these layers of assumptions. But once you’ve done that, the whole question, going back to Baudelaire, of what is “toy-like” or “childlike”—obsessions of modernism—is important. Approaching the “toy-like” with adult seriousness goes back to Wordsworth: the child is father of the man. How does one reclaim what that really meant? That’s a big part of this project. There’s a desire to locate Calder at the forefront of the avant-garde.

ASCRAnd it’s not revisionism. It’s the reintroduction of Calder to people who think of him and Warhol as contemporaries in 1962. This is a reintroduction to say that Calder’s three generations earlier.

JPThe question of the childlike is something Calder was meditating on through much of his life. He had an extraordinary childhood, with parents who recognized the value of everything he did as a child because they valued the importance of childhood—they definitely embraced the romantic vision of childhood. His parents saw childhood as the fount of creativity. Dog was in the MoMA retrospective in 1943. Calder wanted the show to start with this work that he made when he was ten or eleven. That’s him posing the issue—that they’re toy-like but they’re not toys.

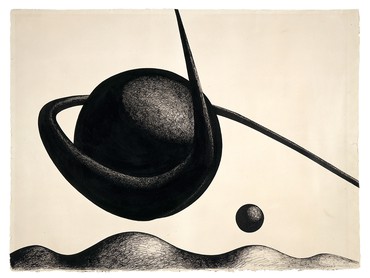

One of the things I love about Calder is that he never said, “I’m making a brooch, that’s like making a sculpture.” He did each of these things with exactitude and expressive power, but he was completely clear about the difference between a sculpture, a spoon for the kitchen, and a brooch given to a friend to wear on her blouse. Each object had a different function and place in the world. James Johnson Sweeney points out, though, that the jewelry-making could have been a way of exploring impulses or ideas that perhaps Calder wasn’t yet prepared to incorporate in his sculpture. This was a man with a mind that was constantly overflowing with ideas. If you look at Calder’s paintings, lithographs, and gouaches, you can see that they also provided him with opportunities to work through ideas—ideas he may not as yet have been prepared to incorporate in the more purely formal language that he generally embraced as a sculptor. Even when he was making toys—he’s making a toy, he understands it’s something for his daughters, but he’s also perhaps experimenting with possibilities that a year or two later he may reimagine in the very different realm of sculpture.

ASCRThe childlike thing, though, has really been a frustration of mine. It’s one of the main reasons I started the Calder Foundation in 1987. Today it’s easier to appreciate that Cy Twombly’s markings aren’t child markings, they’re very sophisticated markings. And you can now more easily relate a Twombly painting or drawing to what Calder was about—not formally, but the way they’ve gotten to the essential nature of things. When I started, thirty years ago, no one would have related the essential nature of Twombly and Calder. Now it’s much easier to comprehend that.

I don’t think we’ve fully absorbed Calder’s work yet, so we can’t know as much as we might want to about its ultimate impact. It could be another hundred years before the scale and significance of his achievement is fully understood.

Jed Perl

JPSomething I realized in the process of writing this book is that Calder, especially in the later years, was sometimes his own worst enemy when it came to shaping his critical reputation. Like many artists who are lucky enough to live and work among a community of like-minded people, Calder didn’t feel the need to constantly explain what he was doing. He believed that his work could speak for itself. Later on, when he was famous and bombarded with journalists asking for interviews, I think he often felt that he couldn’t begin to explain the process that had absorbed all of his energies for the last forty years. So he would say funny, off-the-cuff things—

ASCRYes, rude things too.

JPAnd those have gotten passed around, and they often confuse the story and trivialize Calder’s work. Calder was a man of very deep thought. All too often people don’t fully appreciate that.

ASCRAt a certain point he gave up speaking about his work. In the last thirty years of his life, he really didn’t do that many interviews. Earlier on, he wrote about his work and he did interviews and talked to a certain degree about theory. He spoke to me about grand ideas.

JPI suspect that Calder’s reluctance to philosophize about his own work was at least in part a reaction to his father’s penchant for philosophizing. Calder’s father—Alexander Stirling Calder; he was a very well-known artist in the first quarter of the twentieth century—was a depressive who sometimes spoke about art and life in very dark terms. I think Calder associated his father’s melancholy with a certain kind of philosophic grandiosity. If there was anything Calder wanted to avoid, it was sounding like his father.

ASCRI think Stirling’s melancholy actually helped project Calder’s intellect. One of the great things about Calder is that he’s not dealing with his personal anxiety in his art. He’s dealing with a unification of the human condition and the absolute intention to uplift the human condition, to make our world a little bit better as best he can.

WARight, and a cosmic intention. It was so beautiful reading about when he was outside Panama City on the H. F. Alexander and he slept on the dock and saw the coexistence of the sun and the moon in the sky.

ASCRWell, we can’t mistake that to be so simple as every red disc in every sculpture is the sun.

WANo.

ASCRBut a lot of people have. Or they did in the 1960s. It’s something much grander than the simplicity of that rising sun and the setting full moon, which is like a silver coin, as he called it, on the opposite horizon. It’s the quantum mechanics of the universe, and the precession of the universe, that fascinated him. It’s the thousands of years—26,000—of the universe repeating its cycle. So Calder’s connection to that moment on the deck of the boat was not simply the grand beauty of these two circles but was much more. What’s our place within this immense system? And then that becomes something much greater than our solar system and our universe. So much has been written about Calder and the universe, which was not his subject, but a sad simplification. It’s the universality, right? It’s the interconnection of all things. What’s the binding force of all matter? What exists beyond matter? What’s “empty” space comprised of? It’s something that physicists have been pondering for several decades—string theory—and now, instead of the fourth and fifth dimension, it’s onto the seventeenth or nineteenth dimension. Calder was exploring all of that from a nonscientific point of view.

WASandy, was there anything that Jed came across in his research for the book that really surprised you?

JPThe family’s connection to the Arts and Crafts movement, that was a revelation, right Sandy?

ASCRYes! To me, that’s the greatest aspect of the first half of your first volume. You present a fully realized explanation of Calder’s origins, because before this moment, people speculated, “Oh, he knew about Constructivism,” or he knew whatever, you know—they just made things up. But Jed has drawn very clear lines back to the handmade, this resistance to automation and the return to the essential qualities of the handmade. The hand-hammered piece of metal at the turn of the century was so influential on my grandfather, and Jed has really explained how that was, who he saw and who his parents were involved with.

JPOne of the enigmas of Calder’s career is the ease and grace with which he assimilated very challenging ideas almost immediately after arriving in Paris. There’s never a whiff of American provincialism about his work. When he becomes an abstract artist, in the early 1930s, there’s no sense of strain or stress. He begins by creating some of the most radically simplified abstract sculpture that anybody had ever done; the ideas are immediately there, fully absorbed. How did that happen? Part of the explanation is that even as a child he was moving in a very sophisticated circle. His parents were incredibly sophisticated people and he was imbibing all this stuff. So when he went to Europe, he didn’t have to catch up.

WAHe lived it.

JPRight, he already knew. The whole question of formalism, the nature of form, he got it. Calder’s sister—she was a couple of years older—wrote a memoir in which she recalled how annoyed she and Sandy would be at their parents’ endless discussions about the nature of form and color. So he was living and breathing the language of art from the time he was a child, which I think helps explain the ease he had all those years later. His early immersion in the Arts and Crafts movement—with the kinds of objects that were being made and with the people who were making them—was really the beginning of his education as a modern artist. And he was still a boy.

WAYes, I enjoyed the section about the Calder family going out west—how open the West was, and the Arts and Crafts elements there.

JPRight, everybody talks about Calder and Philadelphia, and yes that’s important, but he spent a lot of important years on the West Coast. My feeling is that the whole West Coast vibe—the ease, the openness—had a big impact on his life.

ASCROh, it’s super important. And the fact that this high culture developed there at the same time that he was there and a few years before he arrived is extremely important. There were other things that I learned from Jed’s research and writing, but that was the first thing Jed presented to me many years ago, this strategy about how to tell the story of Calder’s formative years. I was stunned at how original it was and also how obvious it was. It was so self-evident. But no one had stated it before Jed.

WAWhere do you still see the ripples of Calder in contemporary art? Or do you?

ASCRWell, there is Calder’s pioneering use of industrial materials to make monumental and outdoor sculptures, which one can see carried on in the work of someone like Richard Serra, for instance. But beyond this, I’m more inclined to draw your attention to James Turrell. Turrell sculpts light. He doesn’t make objects, right? And Calder’s involvement with unseen forces is from the beginning, even before he becomes abstract in 1930. Through the vibratory effect of his wire sculptures, he delineates qualities of aliveness. We are always, constantly animated, and the sculptures from the very beginning are about that. Then, shortly after, when he drops figurative wire sculpting, the underlying energy becomes the real subject. So his interest in how light and object exist with you physically in space—and the immediacy of that moment, now in 2017—are directly related to what Turrell’s up to. Turrell creates an experience; Calder’s created an experience. Calder has this extraordinary quality, and his greatest lasting legacy is that his work is experienced in present time.

And there are many artists who have come after Calder who have used other things. Like sound—Calder used sound in his sculptures, overtly for specific circumstances and almost accidentally for nonspecific circumstances. But nonetheless, it’s about the sound waves encompassing your body, your physical presence in the present moment.

JPI think it’s an open question, the question of Calder’s legacy. It’s one I’m going to talk about a little toward the end of volume two. In his essay “The Image of Proust,” Walter Benjamin says that “all great works of literature establish a genre or dissolve one—that they are, in other words, special cases.” I think of this in relation to Calder. Turrell is certainly an interesting person to bring up. There’s something so large about what Calder achieved, I don’t know that anybody has been able to figure out where you go from there. An analogy that I would suggest is with Bernini in Rome in the seventeenth century, and what Bernini did with the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa in the Cornaro Chapel and the later Blessed Ludovica Albertoni. Bernini created these chapels that become total environments, in which the central sculptural unit is related to everything else in the chapel; the entire space is unified, is activated. In the new collection of Donald Judd’s writings, Judd says something like, “Bernini finished off religious art.” There’s a sense in which Bernini’s achievement is so huge that even when you’ve considered all the wonderful late-period Baroque sculpture done after Bernini, you still can’t really say that anybody in the eighteenth century knew how to move beyond him. It may be that nobody figured that out until Rodin came along in the second half of the nineteenth century. Calder is an artist on that scale. I don’t think we’ve fully absorbed his work yet, so we can’t know as much as we might want to about its ultimate impact. It could be another hundred years before the scale and significance of Calder’s achievement is fully understood.

Artwork © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY