Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

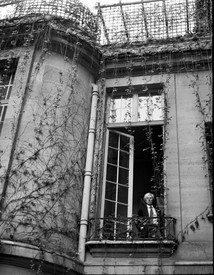

One night in 1963, Andy Warhol attended a hair-cutting party in the East Village. When he arrived, he was met with a sparkling, mirrored interior. Every surface—from the refrigerator to the pipes—was covered in aluminum foil and silver spray paint. This was the apartment of Billy Linich, a photographer, filmmaker, and poet from Poughkeepsie. Captivated by the glittering effect, Warhol asked Linich to recreate it at his newly rented loft space on East 47th Street. The Silver Factory was born.

More than twenty years later, a large silver trunk arrived at Vassar College. In it were photographs and other ephemera from the Factory, offering glimpses of the world of Warhol and his cohorts. The trunk belonged to none other than Billy Linich, who by then had changed his name to Billy Name. Name had become one of Warhol’s Superstars, as well as the Factory’s archivist, and had left the trunk in the Factory, where it was found in 1987, the year Warhol died. He donated the contents of the trunk to Vassar after displaying them in the college’s gallery in 1989. In an interview for Hudson Valley Magazine discussing the Factory, Name traces his attraction to silver back to his childhood in Poughkeepsie. Every year he would watch the city workers repaint the Mid-Hudson Bridge in shiny silver paint.

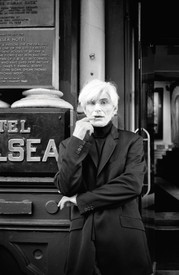

When we think we know a story, we struggle, or simply forget, to question it. With so much of Warhol’s life documented in countless photographs, journal entries, and listed expenses, it is easy to assume that the story is complete, that there is nothing more to uncover. Yet, like Name’s silver bridge, there are always unexpected entry points for new research. People Are Beautiful: Prints, Photographs, and Films by Andy Warhol, an exhibition at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar, which opened on January 26, 2018, offers views from many new vantage points, exploring Warhol’s ideas of beauty and fame not only from the center, but from the periphery as well—illustrating the revelatory power of the oblique.

Mary-Kay Lombino, the exhibition’s curator, began with the spacious theme of portraiture, organizing close to one hundred works into five subcategories: Celebrities and Stardom; Artist-Patron Relationship; Fashion, Models, and the Party Scene; Ladies and Gentlemen; and the “Most Beautiful” Screen Tests. However, as Lombino sorted through the work—made between 1964 and 1985—she quickly began to notice new trajectories in Warhol’s approaches to beauty and its construction. Many of these trajectories cut across disciplines, and grew out of (and into) student and faculty research, revealing the unique advantages of curating in an academic museum. The Billy Name trajectory, rediscovered by one of Lombino’s student assistants, Griffin Pion, even broke off into its own exhibition, which she also curated, titled Billy Name: Inside Warhol’s Silver Factory.

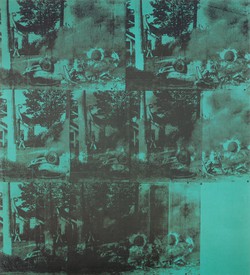

The “Celebrities and Stardom” section of People Are Beautiful includes photographs of instantly recognizable “ideal” beauties, including Jackie Kennedy, Liza Minelli, and even Alexander the Great, showing how Warhol not only examined his own attraction to this type of beauty, but also mastered its artifice. His formula was so fine-tuned that to become famous and beautiful, one merely had to have Warhol depict them as famous and beautiful. And when a patron wanted “a Warhol,” what they wanted was a work with high-contrast, graphic lines, and a bright, commercial palette: the style that, into the present day, one is most likely evoking when saying something looks “Warholian.” Realizing that he could produce commissioned portraits with this relatively straightforward formula, Warhol developed a dependable portrait-making process—one that allowed him to assert a certain degree of power within the art market, while also giving him the financial stability to pursue his filmmaking and photography.

His formula was so fine-tuned that to become famous and beautiful, one merely had to have Warhol depict them as famous and beautiful.

Angela Brown

People Are Beautiful includes several Polaroids of Warhol’s patrons, including Anne Bass, Dina Merrill, and Emily Fisher Landau. As Lombino explains, the patron portraits involved a ritual wherein the artist and the sitter would have lunch and cocktails; then, Warhol would apply white powdered makeup and red lipstick on the patron, and allow her to pose as she wished. As the patron grew more comfortable, Warhol would start to call the shots, asking the patron to extend her neck or tilt her head, as if in a fashion shoot. By the end, Warhol would have a wide range of Polaroids to choose from, merging elements from different ones to create the final portrait. “In a way, he’s robbing them of their authority or their control,” Lombino explained, “and obviously these are people who know how they want to be seen. They’re paying the bills, so he wanted to appease them to a certain extent, but he managed to shift the equilibrium of power in those photo shoots.”

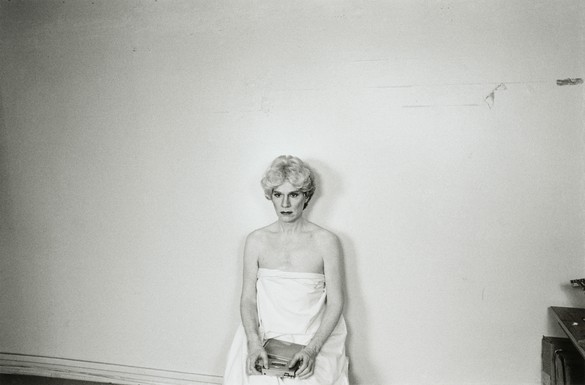

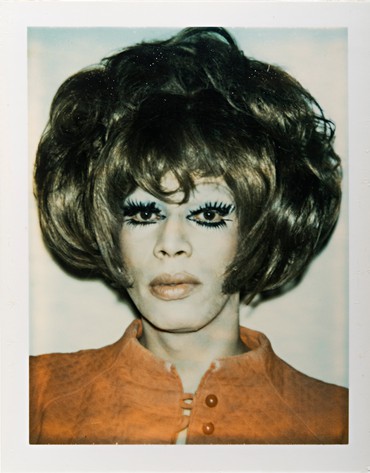

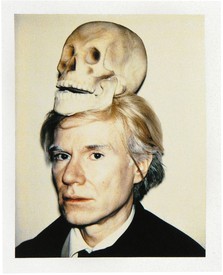

Power plays a different role in the Ladies and Gentlemen series. In 1975, Warhol sent his associates to the Gilded Grape, a bar in Midtown Manhattan, to recruit models for a series on drag queens. Most of the models were people of color, some whose names accompany their photographs and prints, while others remain anonymous. Lombino, looking through the works from this series in relation to the patron and celebrity portraits, noticed that, because Warhol allowed the drag performers to pose and dress themselves, the resulting works possess a striking autonomy that is absent from Warhol’s more typical portraits. Rather than becoming “Warholian” products, the models, such as Helen/Henry Morales, exude a constructed style of their own: a style that surpassed Warhol’s white powder-red lipstick formula. As Lombino observes, the Ladies and Gentlemen series allowed Warhol to explore the idea of “the ultimate constructed beauty.” The drag performers built their specific, feminine beauty from scratch, oscillating freely between the idealization of glamour and the subversion of gender norms. Warhol thus allows the models’ understanding of beauty to overtake his own. A photograph by Ari Marcopoulos in the exhibition shows Warhol in drag. Seated, with a white sheet wrapped around him, he stares blankly ahead, wearing a short blonde wig and makeup echoing that in his celebrity portraits. In such a rare, vulnerable image, it becomes clear that Warhol’s works and his Superstars acted as templates, and perhaps stand-ins, for his own identity. The artist shifted his own appearance in order to become the ideal that he set out to depict in his work.

While in his commissioned works Warhol formed a consistent style—which he imposed upon a variety of subjects—the “Most Beautiful” Screen Tests, as well as the films, illuminate the interpersonal exchange that was the real grist of his work. Warhol shot nearly five hundred Screen Tests between 1964 and 1966. Silent and black-and-white, the films are moving portraits of the various people who spent time in the Factory in the 1960s. For three minutes, Warhol films each person just looking at the camera, creating a sense of discomfort both in the sitter and in the viewer. The Screen Tests in People Are Beautiful feature John Giorno, Dennis Hopper, Paul Thek, Gerard Malanga, Ann Buchanan, Brooke Hayward, and of course, Warhol’s famed muse Edie Sedgwick.

These intimate, durational portraits share the anticlimactic nature of Warhol’s films. As Douglas Crimp argues, one of the main achievements of Warhol’s cinema is that it avoids denouement. In discussing the film Eating Too Fast (1966), Crimp writes, “There’s heavy breathing, but no sure climax, sexually or narratively. And the film runs out.”1 Warhol is a master of background noise, of the reality existing beyond the perimeter of the screen or canvas, and People Are Beautiful gives a new generation of students direct access to this mastery of the unseen and its radical rejection of phallocentric climax in art and film. Another of Lombino's student assistants, Sofía Benitez, began to consider Warhol’s films and photography in relation to her Queer Theory coursework, exploring the role of the camera as a mediator between the photographer’s body and the subject. “Warhol set a precedent for how to look with and through a camera,” Benitez explained. “His fragmented pictures of [Jean-Michel] Basquiat's body, for example, created new anatomies and abstractions—in a way reconfigured vision itself.” From posing his models to directing the stars in his films, Warhol changed what it meant to represent a body. Further exploring the depiction of social and sexual relations, as well as themes of death and drug use, on March 29, three of Warhol’s films will be screened at Vassar: Blow Job (1964), Lupe (1966), and Mario Banana, No. 1 (1964).

More than any other artist before him, Warhol was able to construct an entire scene around his artistic practice. The Factory was a sort of Gesamtkunstwerk, fervently documented from all angles. And though this phenomenon of hyper-documentation was rare then, it is completely common today; technology gives individuals the ability to record every moment, conversation, and experience of their lives. For Lombino, curating People Are Beautiful raised several important questions about collecting in an academic museum. Looking through the breadth of raw materials, much of which was donated by the Andy Warhol Foundation, she asked herself “Should all of these photographs be included in an art museum collection?” And, after seeing how much the story could expand, her answer was a resounding “Yes.”

When there is so much information, there is no clear way to determine what should be treated as precious, and therefore make its way into the history books. However, the construction and revision of art history is not a matter of red line edits. Instead, it involves the meticulous investigation of what is missing, or what has been relegated to the sidelines. It is through this kind of investigation that the big questions arise: the questions that can complicate a name as ubiquitous as Warhol, and the questions that can reshape the contours of history as we know it. It was at Vassar, after all, where Linda Nochlin asked “Why have there been no great women artists?” mobilizing a feminist art history that continues to spread its roots.

The questions continue in People Are Beautiful, in which the profound influence of Warhol’s community is revealed as the very fuel behind his constructions of beauty and fame. What these portraits show is that Warhol was not only an artist, but he was a medium as well, willingly molded by the many artists, patrons, and models in his orbit, who reshaped his identity and his work with their own definitions of beauty.

1Douglas Crimp, “Our Kind of Movie”: The Films of Andy Warhol (MIT Press, 2012), 19.

People Are Beautiful: Prints, Photographs, and Films by Andy Warhol is on view at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Poughkeepsie, New York, through Sunday, April 15, 2018. It is part of a yearlong series of Warhol exhibitions, collectively titled Warhol × 5, which will take place in academic museums across the Hudson Valley. The participating institutions—the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College; the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, SUNY New Paltz; the Hessel Museum, Bard College; the University Art Museum, SUNY Albany; and the Neuberger Museum, SUNY Purchase—pooled their inventories and exchanged Warhol works, many of which were donated by the Andy Warhol Foundation, according to chosen thematic arcs including portraiture, children, and celebrations.