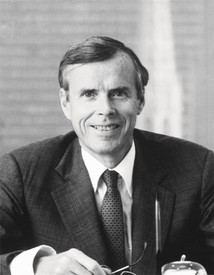

Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

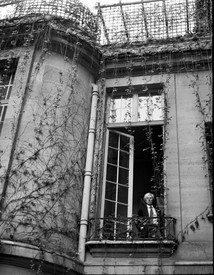

Mary Ann Caws is Distinguished Professor Emerita of English, French, and Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She is the recipient of Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Fulbright fellowships, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and an Officier in the Palmes Académiques.

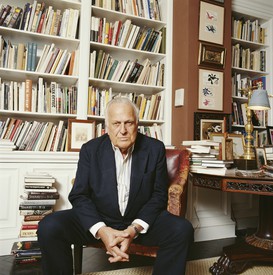

Charles Stuckey is a widely published independent scholar who has served as curator in major US museums including the Art Institute of Chicago, helping organize highly acclaimed retrospectives for Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, and others. He is currently head of research for the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Yves Tanguy.

Charles StuckeyHow did you decide to make The Modern Art Cookbook?

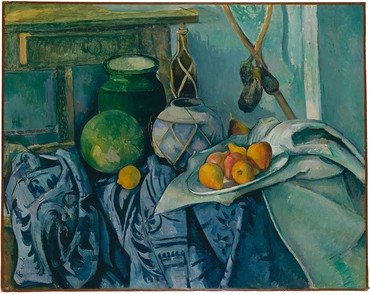

Mary Ann CawsMy grandmother was a painter and a cook. She would take me to the Met and say, “You can only see three paintings, so be sure which ones you want to see first.” My favorite was always Cézanne’s Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants [1893–94]. The eggplants! That’s what started it.

Making the book was exciting. It’s organized according to how you arrange your meal. People who really write wonderfully about cooking were the inspiration for the book. Ironically, though I’m passionate about ice cream, my publisher couldn’t bear ice cream, so there could be no ice cream recipes in the desserts, only fruits. Luckily there are lots of fruits in still lifes [laughter].

And it came full circle in regards to Cézanne, as I include his recipe for anchoïade. As I mention in the book, Cézanne’s favorite dish to take on a picnic was eggplant rolled over with anchovies in the middle.

CSHow did you ever find out about Cézanne’s recipe?

MACThere was a show of Cézanne and Picasso at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence. I found a cookbook there, La Cuisine selon Cézanne, and nobody had ever translated it into English. So that’s where it started.

CSThe Monet Cookbook: Recipes from Giverny was also published recently. This interest in the private lives of artists seems pretty new, mostly starting in the early 1960s. Before that, if you read a book about an artist, it wouldn’t mention his wife and children, much less what they liked to eat.

MACYes, that’s right.

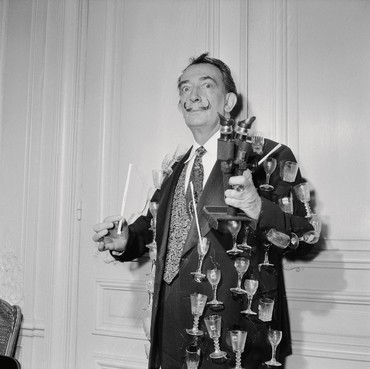

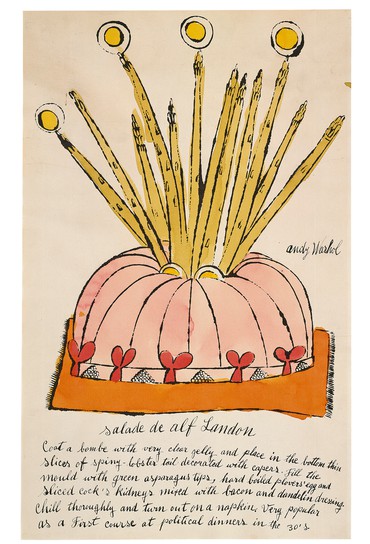

CSBut Andy Warhol published Wild Raspberries in 1959, with Suzie Frankfurt, and Salvador Dalí published Les Dîners de Gala in 1973, and both found an audience.

MACYes. The idea that life has something to do with art does seem to gain steam by 1960. Now it’s everywhere! To go back to Cézanne, after I discovered La Cuisine selon Cézanne I made a lot of the recipes. I became so meticulous that I only wanted to use the red wine that he would have used in his mulled-wine recipes, and the oranges that he would have used when he made orange marmalade, and so forth. It was ridiculous, because actually what he liked eating was just potatoes and olive oil and garlic. But he had this housekeeper, Madame Brémond, and she wrote about “affectionate vegetables.” I loved the idea that you should use leeks because they were more affectionate than onions. Cézanne really is all the way through The Modern Art Cookbook.

CSFascinating.

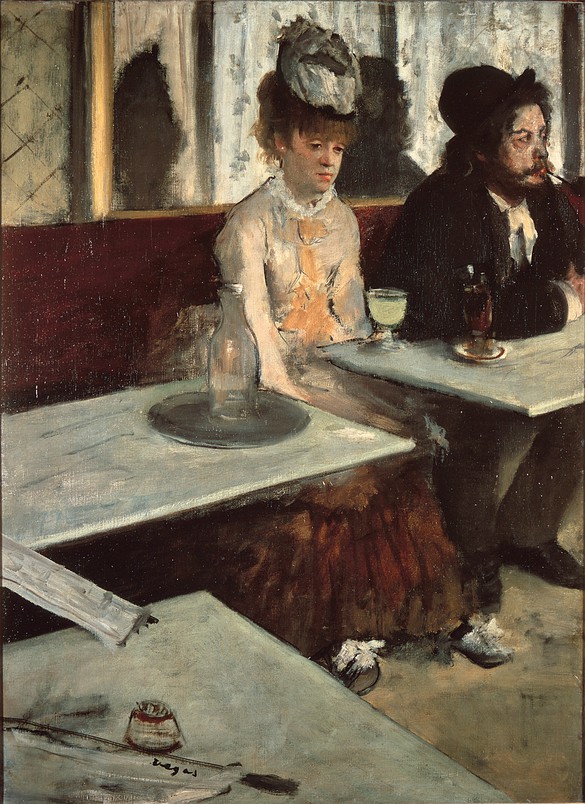

Wyatt AllgeierThat transition from, say, Cézanne’s Madame Brémond, housekeepers, and picnics to the rise of café culture and public dining as a place for creative thinkers to gather is interesting. And art comes out of that. The Café Guerbois in Paris, for instance, where Manet, Degas, and others used to go—Manet did a painting of the owner in 1873, Le Bon Bock. Do you know that painting?

MACYes, absolutely. My next book—forthcoming with the same beloved publisher, Reaktion Books—is about art colonies and salons and cafés. It’s tentatively entitled Modernist Gatherings: Tables and Moments.

CSThe cafés became epicenters. We tend to forget that Manet and earlier generations of artists didn’t have electricity [laughter], so at a certain point your workday was essentially over and you had to hang out someplace else.

MACAnd typically they had to be cheap places, so cafés, not restaurants.

CSYes. I think that’s partly why so much of that life shows up in early modern art, starting with Impressionism.

MACIt’s interesting to me that things often appear over and over, almost ritualistically. Cafés were this way—artists always met at the same café. There was a sort of sacredness about it, which I find fascinating.

WAThere seems to have been an interest in table settings as well. Picasso worked in ceramics and made a lot of plates and pitchers, and Dalí made a set of cutlery in 1957.

CSIt seems to me that one of the breakthrough works of art in all of this is that wonderful sculpture Picasso made of an absinthe glass, Glass of Absinthe from 1914.

MACOh yes.

CSAnd that sculpture incorporated real elements, like a spoon, into what was otherwise a nonrealistic sculpture, which connects to ideas about incorporating life into art.

Mary Ann, with your rich literary background, do you have any thoughts about the possible connection between Proust’s Swann’s Way, where biting into a madeleine brings about an intellectual, memory-based explosion, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where eating the cookie changes the world around you? Could Proust possibly have had that in mind? Alice in Wonderland was published nearly fifty years before Swann’s Way. But then again, the theme must go back to antiquity, right—the story where you eat something and then the world changes for you, your whole outlook?

MACYes, it’s there in Boccaccio, where you have a group around a table and whatever you quaff or eat introduces the story you’re about to tell. I love this thread about the madeleine de Proust and the Alice tale. It leads to The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book from 1954, with its wonderful brownie recipe, allegedly provided by Brion Gysin, but also to The Book of Salt, a novel by Monique Truong from 2003—she makes up a Vietnamese chef who cooks for Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein. Of course it’s an invented chef, a fiction, but somehow it transports you, almost as if you were sitting around the table with artists and then they went out to paint. Or if they’re composers they go out and write scores, or if they’re writers they go out and write. They take the table to the canvas, the score, the page. To me that connection is what’s really exciting. Consumption and creation—and don’t forget consummation.

The legend behind Meret Oppenheim’s Déjeuner en fourrure [1936], for example, her fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, ties in nicely to food. Picasso and Dora Maar were at Café de Flore with Meret, who was wearing a fur bracelet that she had created for Schiaparelli. Picasso looked at the bracelet and said, “You could make anything from fur.” So it’s about fashion and class, but it’s also an undeniably erotic thing—the hair, and drinking from the hair. It’s all there, and interestingly it’s then taken into art history as rather sterile—“Oh, a fur teacup.” Well [laughs], yes and no.

WAThat’s from the same year Oppenheim did My Nurse. Are you familiar with that one? It’s a platter with two white heels from a pair of woman’s shoes sort of bound like a roast chicken.

CSRight. The shoes are presented on a platter as a dish.

MACThat’s fashion, food, sex, and art once again. Very dishy.

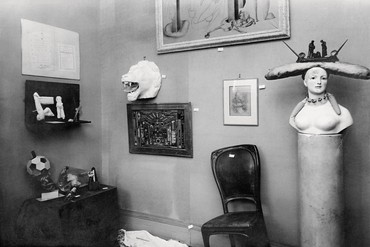

CSThis is all from 1936, but to think about firsts, I’ve had a hard time finding an earlier example of real food being incorporated into a work of art than the pieces presented by Dalí in a group show in 1933. That would have been the immediate inspiration for Oppenheim and these other Surrealist objects. In Retrospective Bust of a Woman, for example, Dalí put a baguette on the head of a mannequin. There’s the funny story that going to see the exhibition, Picasso’s dog ate the baguette [laughter], which had to be replaced.

MACDon’t you love it? Of course! It had to be Picasso’s, right? It couldn’t be anybody else’s dog.

CSAnd in the same room, I mean right next to the baguette piece, was a work that tragically is lost to us: an oddball Art Nouveau chair that had been given to Dalí, who loved Art Nouveau, by the designer Jean-Michel Frank. Scatologically enough, Dalí had the idea to have the seat cast in chocolate and then to present it as an art object. And then he put one of the legs of this chair into a glass that was half full of beer. So viewers would have had the aroma of chocolate and beer. Surely that was one of the first times an art gallery produced such an experience. There’s a lovely photograph of the work by Man Ray, but you don’t get the sensory richness in full. It’s nice to look back at that and calculate the impact, how from a tiny little splash the ripples expanded—today it’s become more ubiquitous to incorporate real food into works of art.

WAAnd then there’s Dalí’s Rainy Taxi installation in 1938, where there was an omelet in the mannequin’s lap.

MACDalí’s favorite meal was oursinade, sea urchins—he would eat three plates of them. And then, thinking about sea urchins, Picasso has that wonderful recipe for scramble in sea urchin shells, and Renoir loved having a sea urchin sauce over things. So we see how one element radiates into all sorts of art and food. It’s something that connects us. That’s why meetings at cafés work—gathering people around a table, focusing, discussing, absorbing, and then moving into whatever else they’re doing for the rest of their creative day.

WAYes. And it seems that some were more conscious of that than others. For instance, the Futurists: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was very interested in revolutionizing cooking, whereas while the Surrealists worked with food, I haven’t found anything that says they wanted to revolutionize cooking in the way the Futurists did.

MACNo, me neither.

WASo it’s interesting how these different groups of visionaries and thinkers addressed food—was it just a material, or was it part of an aesthetic revolution that they were seeking?

MACIn part, that brings us back to ideas about ritual. The Surrealists were committed to drinking the same thing at the same hour in the same café, every day.

WAGeorges Bataille, too, was obsessed with the importance of ritual.

MACYes, and this makes me think about Raymond Roussel, who made a star-shaped glass box that encased a star-shaped biscuit. As in his play L’Étoile au front [1924], the star is a crucial element. Attached to this star-shaped biscuit and glass case is a note that states, “A star originating from a lunch I attended on Sunday July 29, 1923, at the Observatory at Juvisy with Camille Flammarion presiding.” Flammarion was a popular astronomer from that time. Some years later Dora Maar found this cookie in a flea market in Paris. She was living with Bataille at the time, and when she left him, Bataille found this strange object in his drawer. I will read you what he said, because I love it and it ties in nicely into our conversation here:

The star did not belong to me, but it remained in my drawer for several months, and I could not speak of it without feeling troubled. Roussel’s obscure purpose appeared to be closely connected to the fact that the star could be eaten. He obviously wanted to appropriate to himself this edible star in a manner more important and actual than simply by eating it. The strange object signified for me the way in which Roussel had achieved his dream of eating a heavenly star.

Roussel’s L’Étoile au front leads into a lot, not just Surrealism but American poetry, through John Ashbery, who learned French in order to read Roussel. This star and this biscuit go from place to place, like the madeleine de Proust in many ways, so that all these people and memories meet.

CSI imagine that if you study modern literature and early cinema, the perception, the appearance, of food is a springboard to symbolism, whether in terms of desire or social class or whatever. I was once lucky enough to see a short homemade film that Luis Buñuel made when he was visiting Dalí in Cadaqués one summer [Menjant garotes (Eating sea urchins), 1930]. He decided to show Dalí’s father (who famously disowned the artist later on) eating a huge plate of sea urchins. It’s a silent movie, so there’s a phonograph spinning silently, and then it just shows this large man indulging in a plate of food. You can feel Buñuel’s distaste for class and privilege, and how film can miraculously portray it and pull the rug out from under it at the same time.

WAThen there’s Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie [1972]. The whole movie is the bourgeoisie trying to get together to eat, and it never happens.

MACRight. That seems to get at transubstantiation, embodiment, and the absorption of the talisman as ritual. This goes literally and symbolically all the way through the representation of the ingestion of food. The madeleine and the rest: it goes into all of literature, art, and everything without anybody having to say, “Oh, guess what? We’re referring to Proust” [laughter].

CSDo you think Giorgio de Chirico read Proust? Do you think those wonderful metaphysical interiors where he shows imaginary paintings—

MACYes, I do. The de Chirico painting Le Salut de l’ami lointain [Greetings from a distant friend, 1916], where you have the biscuit at the bottom.

CSFifteen years later Dalí is putting real food on display, but de Chirico is already imaging it.

MACExactly.

CSIt’s a shame he never really made them, but he’s portraying a studio with pictures where someone has taken biscuits—cookies—and glued them onto abstract canvases as collage events. It falls right into what you were saying about transubstantiation—the suggestion that if you want to understand your art, you should eat it.

WAIt’s interesting that The Last Supper was one of the most popular topics of Christian art. A lot of the artists we’re talking about have done their own Last Supper interpretations. Dalí did a Last Supper, and—

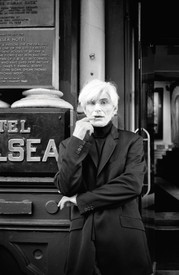

MACWarhol.

WAYes, that’s interesting—the gathering, the supper, and, of course, transubstantiation.

MACIn 1987, one of Warhol’s Last Supper paintings was shown right across the street from Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in Milan. And of course Warhol was quite religious, as some tend to forget.

CSYes. Transubstantiation, that moment of the Eucharist, seems to me in some ways the culmination of the food myth of Genesis: the idea that reality and our existence—that we’re doomed to know it—comes from taking a bite. Original sin is commenced through food!

MACAbsolutely. And a bite is often enough. You wouldn’t have to have the whole meal; just a bite is enough to symbolize the whole thing.

CSYes. The power of suggestion.

MACThere you are.

CSAll of this leads into, I suppose, the culture of unprecedented decadence that we’re living in right now, which is marked most of all by the Pop art revolution, where we all came to agree that ordinary things could interest us as much or have as much importance as something from the canon. With this flood of food in art, food preparation as art, and food serving as art, we arrive at one of the building blocks of twentieth-century American culture. Warhol didn’t stop at illustrating Amy Vanderbilt’s cookbook, he went on to actually make paintings of soup cans and record jackets with bananas. And in doing so he was simply keeping up with Wayne Thiebaud and Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns and Claes Oldenburg—it goes on and on.

Food art has come into its own by, let’s say, 1970. What, though, compels artists to use food as a material? Ed Ruscha made works on paper where he was applying color with spinach and beets and things that you would never have imagined. Or those Vik Muniz works where sugar and chocolate are simply what he challenges himself to use to re-create his memories. It adds to a sense of wonder, in a way.

MACYes, and one must ask, what kind of specificity makes it more or less exciting? When do we care about the specificity of the foods that are used? Is it only if we are going to have to consume it afterward, before it molds?

CSWell, I can’t think of too many pieces where the concept allows the food to go bad, though it surely presents a conservation problem for the future. It seems to me that there’s a preference in these works for shells and exoskeletons—urchins and lobsters and mussels and eggs. They all play leading roles in the drama of food and art—because they are indestructible, perhaps.

MACYes, think Dalí and his fondness for the exoskeleton. But I’m trying to get at the question of narrative. Exactly what you are using in art is important. If it decays, if it’s affected by time, this is important.

CSRight.

MACDalí’s chocolate doesn’t decay. Though it could melt.

CSRight, and of course Felix Gonzalez-Torres created an installation that’s a mountain of hard candy. That has become one of the seminal works of the late twentieth century.

MACYes. And you’re invited to take some. Another ritual act.

WAIn that instance they don’t go to waste or get moldy, they end up consumed. It’s a different narrative.

CSWell, it’s interesting that so much great art of the twentieth century was created to be fleeting or is lost, and was really only appreciated as it was documented or recorded. If you were to do a serious history of modern sculpture, many of the significant pieces don’t exist anymore. Artists are able to use temporary materials now, because we document so much more than people were able to do in earlier generations. In early modernism there was the option of documentation, certainly, but new technologies liberate twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists to think differently about materials.

MACWhat’s your favorite work of art that incorporated food?

CSDalí’s Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket [1936].

MACOh, the jacket was wonderful. Some dinner!

CSThat would be one of the works where the original is gone. But if people were to drink the crème de menthe, you would just fill the little glasses up again and be right back where you started.

MACOf course. A replaceable piece of art. Replaceable—not imitable, but replaceable. Pour the liquid back in.

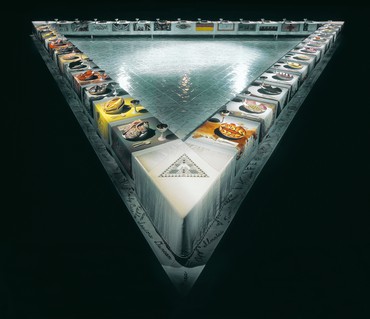

CSExactly. And that’s the secret of the Gonzalez-Torres, that it’s ongoing, and in his case it feels like a meditation on everlastingness. But we need to talk about Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party. I can’t think of a more ambitious or successful work of art about food than that.

MACThat’s right. The eroticism of it is fantastic and the wit is over the top.

CSAnd it brings this delirious extreme to the fur-lined teacup and the other Surrealist objects. Did you ask Chicago for a recipe for your book?

MACI did not, but I would if I were doing it again. I was told I should do a postmodern cookbook.

WAWhat artist would you be most curious to receive a recipe from?

CSJenny Saville or Urs Fischer, I think. What about you?

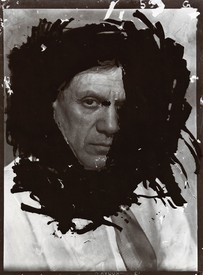

WAFrancis Bacon. I know he was fascinated by food—I read that he would read cookbooks at night, and he loved one in particular, Mrs. Beeton.

MACMrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management. It’s wonderful, yes indeed. Bacon was the person whom Robert Motherwell would always talk to me about. He would say, “There’s so much in Francis Bacon I want to be like.” You cannot imagine two more different people! That idolization of or confrontation with an opposite person is how I would approach the question. So were I to ask for a recipe from somebody, I would probably choose somebody who didn’t like anchovies and peppermint ice cream. I’d probably choose somebody like Marcel Duchamp, who only ate simple things, like white spaghetti with very little sauce and one glass of wine.

A Chronology

of Art and Food:

Highlights from over 150 years of delicious history by Charles Stuckey

1825

Publication of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s book Physiologie du goût, ou Méditations de Gastronomie Transcendante. Among the many gastronomic axioms Brillat-Savarin gifted to the world, the most famous remains “Tell me what kind of food you eat, and I will tell you what kind of man you are.”

1860s

Decorative-arts entrepreneur extraordinaire William Morris, along with James Gamble and Edward Poynter, decorates the café at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Previously known as the Green Dining Room of the South Kensington Museum, it is now known as The William Morris Room.

1865

Publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, with illustrations by John Tenniel. On the first leg of her journey through Wonderland, Alice encounters a bottle labeled “drink me” and a cake marked “eat me.” These comestibles transform her in ways necessary for her journey.

1876–82

Modernizing the old master genre, Gustave Caillebotte paints still lifes such as Calf’s Head and Ox Tongue (1882), Still Life with Crayfish (1880–82), and Calf in a Butcher Shop (c. 1882), showing food served in restaurants and meats on display to be sold.

1887

Nearly three years after painting his early masterpiece The Potato Eaters, Vincent van Gogh organizes an exhibition at the Grand Bouillon–Restaurant du Chalet, Paris, with his own paintings and works by his comrades Louis Anquetin, Émile Bernard, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

1889

To take advantage of world’s-fair tourism in Paris, Paul Gauguin and friends organize a June–October exhibition of their “Groupe Impressionniste et Synthétiste” at the Café des Arts on the Champ-de-Mars.

1895

Lautrec produces the lithograph La Bouillabaisse, Menu Sescau, a humorous menu for the opening banquet of the play Les Pieds nickelés, by his friend Tristan Bernard. In later years he will continue the idea with the lithographs Suisse Menu and Menu Le Crocodile.

1896

Founding of the Caffè Giubbe Rosse (under the original name Fretelli Reininghaus) in Florence. The café will become a crucial hub for the Futurist movement, attracting artists and writers such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Umberto Boccioni and serving as de facto office space for a number of literary journals, from Solaria to L’Italia Futurista.

1900

Self-exiled in Tahiti, Gauguin makes eleven differently illustrated menus in watercolor for the guests at a banquet he hosts.

In Homage to Cézanne, a group portrait of Cézanne’s young Symbolist admirers, Maurice Denis represents the master through one of his still lifes, Fruit Bowl, Glass and Apples (1879–80), then in the collection of Gauguin.

1911

Founding of the Café de la Rotonde in Montparnasse. Run by by Victor Libion, the café will go on to be frequented by Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, and many other artists. It will also receive a nod in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises (1926).

1912

Picasso creates La Bouteille de Suze, a depiction of a liquor bottle and a cigarette, paired with actual newspaper and other collaged materials in a flattened space. The work translates a simple pedestrian morning at any Paris café into Picasso’s revolutionary Cubist collage idiom. By 1914, Juan Gris will specialize in Cubist still lifes incorporating the labels from bottles of his favorite aperitifs.

In the same year, the composer Erik Satie writes in his Memoirs of an Amnesiac, “My only nourishment consists of food that is white: eggs, sugar, grated bones, the fat of dead animals, veal, salt, coconuts, chicken cooked in white water, fruit mold, rice, turnips, camphorated sausages, pastry, cheese (white varieties), cotton salad, and certain kinds of fish (without their skin). I boil my wine and drink it cold mixed with the juice of the fuchsia. I am a hearty eater, but never speak while eating, for fear of strangling.”

1913

The consumption of a madeleine is the sparking event in the first volume of Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time: Swann’s Way. Like the cookie in Alice in Wonderland, this little cake triggers an amazing reaction in the person eating it, this time entrée into his memories.

1914

As if responding to Boccioni’s revolutionary Futurist sculpture Bottle in Space, Picasso creates a Cubist Absinthe Glass as an edition of six bronze casts, each painted differently. Extending his collage revolution into the realm of sculpture, he surmounts each bronze glass with a real absinthe spoon.

1916

Giorgio de Chirico produces paintings—Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits, Death of a Spirit, The Revolt of the Sage, The Greetings of a Distant Friend, and others—that include representations of imaginary paintings with biscuits and candies adhered to their surfaces. Had de Chirico actually made such collages with real foodstuffs, at this date they would have been unprecedented.

1922

Founding of Le Boeuf sur le Toit (The ox on the roof), by Louis Moysés. This Paris cabaret will attract many artists, writers, and musicians, including Picasso, Satie, René Clair, Jean Cocteau, and Darius Milhaud.

1923

Inspired by Gris, the young Salvador Dalí joins the avant-garde by inserting miniature toy spoons and plates into his Cubist collage Pierrot with a Guitar.

1927

The Art Deco brasserie La Coupole is opened by Ernest Fraux and René Lafon. This Paris restaurant will be frequented by a wide spectrum of influential artists and writers, including Josephine Baker, Marc Chagall, Alberto Giacometti, Yves Klein, Man Ray, Jean-Paul Sartre, and many more.

1930

Maurice Joyant publishes Lautrec’s La Cuisine de monsieur Momo, also known as The Art of Cuisine. With over 150 original recipes, artworks, and menus, this posthumous publication seemingly holds the distinction of being the first artist’s cookbook.

1932

Dalí paints Oeufs sur le plat sans le plat (Eggs on the plate without the plate). The painting’s source of inspiration, according to Dalí, was the experience of being in the womb, which he will (somehow) recall was like seeing “a pair of eggs fried in a pan without a pan,” adding that the “intrauterine paradise was the color of hell.”

1933

At a Surrealist group exhibition in June, Dalí displays an unbalanced Art Nouveau chair, the seat of which is cast in chocolate while one of its legs stands in a glass of beer. Next to this he shows his Retrospective Bust of a Woman, adorned with a necklace of ears of corn and a hat made from a real baguette (in the event, eaten by Picasso’s dog). This is followed by a solo exhibition for which Dalí provides his own catalogue introduction, where he proposes a table made half of poached eggs, half of stone—the whole to be hung at the top and within the shaking leaves of a pair of poplars.

1936

For a Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Charles Ratton, Dalí creates Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket, an actual jacket embellished with shot glasses of crème de menthe.

1954

Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein’s life partner, publishes The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book. Part cookbook, part autobiography, part window into history, the work bridges many genres while still providing real recipes.

1956–57

Wayne Thiebaud, while on leave from his professorship at the University of California, Davis, visits New York City, where he begins painting pictures of cakes displayed in bakery windows.

1958

Robert Rauschenberg creates Coca-Cola Plan, a three-dimensional work incorporating three Coca-Cola bottles. Works of this kind, termed “Combines” by Rauschenberg, were created to address the interchange of art and life in popular culture.

1959

Meret Oppenheim stages Spring Banquet at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris. For the opening, a live woman, garnished with fish, fruit, and nuts, lies on a table set with cutlery. Much to Oppenheim’s chagrin, the Surrealist leader André Breton will later rename the work Cannibal Feast.

1959

Andy Warhol and his friend Suzie Frankfurt, later a renowned interior decorator, together create Wild Raspberries, a whimsical cookbook with recipes such as “Seared Roebuck” and “Roast Igyuana Andalusian.” The book contains nineteen of Warhol’s hand-colored illustrations; the first edition, a run of thirty-four hand-bound books, is mostly given to friends. The book will be republished for a mass audience in 1997, when Frankfurt’s son Jamie discovers an original in his mother’s belongings.

1960

Daniel Spoerri makes his first “snare picture,” Kichka’s Breakfast, created by affixing a “found situation,” in this case his girlfriend’s leftover breakfast, to a board. Spoons, a coffee tin, cigarettes, an eggcup, and more are left exactly where they were found; the board is mounted to a chair, which in turn is hung from the wall.

1960–61

In response to Willem de Kooning’s quip about dealer Leo Castelli—“Give [him] two beer cans and he could sell them”—Jasper Johns creates Painted Bronze (Ale Cans), a set of two Ballantine ale cans cast in bronze.

1961

Warhol provides illustrations for the best-selling cookbook by famed queen of etiquette Amy Vanderbilt.

1961

Pop art pioneer Claes Oldenburg creates Pastry Case, I, a found display case holding a candy apple, ice cream, cake, and other desserts—all handmade, the ingredients being plaster, burlap, muslin, and paint.

1965

Edward Kienholz’s installation The Beanery re-creates the famous Los Angeles pub Barney’s Beanery as a warped, unruly scene, complete with bar-goers (with clocks for faces), a poodle, alcohol bottles, a soundtrack of glasses clinking and laughter, and even a depiction of the pub’s owner Barney himself.

1965

Marcel Broodthaers begins to make his famous series of sculptures accumulating dozens of either egg or mussel shells.

1968

Arakawa’s Taste It silk-screen features a found recipe for fried pork with sweet-sour sauce, culminating in more than a dozen arrows, evidently as instructions for the cook to follow.

1970

Dieter Roth creates Gerwurzkasten (Cupboard of Spice), a series of wooden cabinets filled with undulating layers of spices. The sculptures, either mounted to the wall or freestanding, interact not only with the audience’s sight, but also through smell, as the aromas of the different spices form their own type of variegated landscape.

1973

Dalí publishes the first edition of Les Dîners de Gala, a Surrealist homage to his wife, Gala. With over 120 recipes and a trove of original illustrations, this cookbook becomes a cult sensation. From bizarre to scrumptious, the recipes are consistently decadent and, as the preface reifies, “uniquely devoted to the pleasures of Taste. Don’t look for dietetic formulas here.”

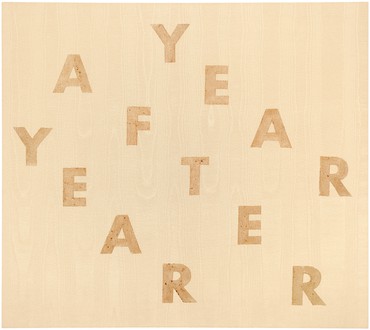

Ed Ruscha begins to make word paintings and works on paper with pigments sourced from food, including cilantro, coconut milk, spinach, ketchup, cherries, blueberries, and more. One work, Mr. Chow L.A., commissioned by the prodigious restaurateur Michael Chow, includes pigments derived from oyster sauce, red cabbage, soy bean paste, red bean paste, red beets, and a “secret ingredient.”

1974

Hannah Wilke begins her S.O.S.—Starification Object Series, which focuses on eroticism and women’s liberation. Many works in the series incorporate “vulval” sculptures made of chewing gum.

1979

Judy Chicago completes her monumental sculptural installation The Dinner Party. The work, begun in 1974, consists of a triangular table bearing thirty-nine place settings, each a unique set of customized china, chalice, and napkin. The table celebrates groundbreaking women throughout history, from Sappho to Virginia Woolf. It stands on Heritage Floor, made of porcelain tiles and inscribed in gold with the names of an additional 999 women who have positively affected history.