Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

What is the function of a portrait? To memorialize? To capture someone’s “essence”? These questions run throughout the history of visual culture—from the Roman death masks of antiquity to the covers of fashion magazines. In his exhibition, Innocence II, Roe Ethridge complicates the questions of portraiture, revealing how various layers of the self coalesce within a single image, whether an iPhone screenshot, a nude self-portrait, or a photograph of one’s childhood home. Using his own past as source material, Ethridge locates the intersection of recognition and estrangement, tracing the history of photography along the way.

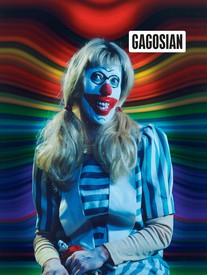

For Innocence II, Ethridge has, for the first time in his career, printed large-scale photographs on brass. Seven of them feature overlaid portraits of his long-time muse and collaborator, Louise Parker, resulting in spectral, hybrid faces—their distorted features fading in and out as if in a cinematic montage. At first glance, the photographs are romantic, naïve even, with Parker wistfully gazing into the camera, her blond hairs blowing in the breeze. Yet silhouetted objects, brick walls, and decals of Looney Tunes characters further transform the portraits. In Louise on Brass #2 (2017) four eyes gaze out at the viewer, two mouths overlap, and the contours of Parker’s hair and face multiply, producing a dizzying effect. The brass shines out from in and around these details, illuminating and reflective. Beauty veers toward monstrosity, and as the viewer tries to distinguish between the overlapping images, he catches a glimpse of himself.

A reflection of the present within an image of the past. Perhaps, conceptually, this is one of the primary goals of art itself. Photography’s origins manifested this effect as a physical reality in the mid-nineteenth century with daguerreotypes. Daguerreotypes were mirrors—silver-plated copper or brass sheets, which were polished, placed in specially designed boxes, and exposed to light for several minutes or more. The light would enter through a lens and hit the metal sheet, reflecting the scene outside, which was kept in place with mercury vapor. The photographic process, though based in science, felt a lot like magic. It immortalized a moment. But moments, of course, are not meant to last forever. Photographs—back then, and now—are ghosts, documents of what is no longer (and on some occasions that which never existed at all). Photographers like Ethridge push the limits of this paradox by distorting the image, staging scenes that resemble reality, but are not “real.”

In the early twentieth century, Eugène Atget called his photographs “documents,” opening up the question of an image’s truth. Framed by the photographer, exposed for seconds or minutes, every photograph presents a specific scene that can be printed over and over, but which can never exist in the real world again—like the reflection of a man nestled among the mannequins in a shop window, or Louise Parker’s eye floating over the chipped paint on a brick wall. Ethridge’s transparencies present his own “documents” (pulled from his previous work), with an elusive, alchemical air, echoing the way images seem to float just above the metal of a daguerreotype.

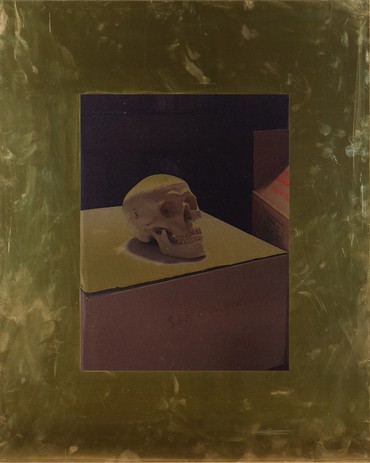

Ethridge has explained that Innocence II is a “loosely autobiographical” exhibition. The photographs of Louise he included, for example, were the first he ever took with her and in them he perceives a certain purity, an earnestness that becomes more pronounced as time passes. He also visited his childhood homes in the suburbs of Miami, observing illuminated windows, minivans, and palm trees as an outsider, a voyeur in the setting of his own past. When trying to remember one’s former self, all that becomes clear is that it is impossible to become that self again. This nostalgia has been the subject of artistic consideration across genres, and Ethridge alludes to several major techniques and traditions that have sought to communicate the sensation. For example, three smaller brass works in the exhibition correspond to the three ages of man, a common theme in Renaissance painting often represented as childhood innocence, the carnal desire of manhood, and death. Ethridge coyly parallels these three ages with a portrait of himself at six years old, taken by his father in the park; a nude portrait as an adult, standing before a mirror with a cellphone camera; and a plastic replica of a skull, which, upon closer inspection, has a goofy underbite. Despite its slight facetiousness, Skull on Brass (2017), with its dark eye sockets and eternal, unmoving grin, cannot shake its status as a memento mori, reminding the viewer of their mortality. In the vanitas paintings of the Northern Renaissance, the skull was placed among other indicators of time’s unstoppable progression. Still lifes were composed of wilting flowers, rotting fruits, and hourglasses, each surface painted with the utmost detail. In Innocence II, Ethridge offers the suburban equivalents: red roses peeking through a white picket fence, mango yogurt on the tips of fingers, dandelions sprouting where the sidewalk meets the edge of the lawn. The skull merely makes explicit what Roland Barthes describes as “that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead.”1

Considered together, the wide-ranging photographs included in Innocence II reintroduce past notions of alchemy, nostalgia, life, and death to the more fast-paced image culture of today. Ethridge expands the parameters of portraiture to include self-appropriation, temporal meditation, science, and disguise. Whether alluding to the black mirror of the iPhone screen, with a scaled-up image of Kellyanne Conway in mid-sentence, or depicting himself as pregnant, the “essence” Ethridge captures is one of intentional multiplicity, of the concurrence of many truths and non-truths.

1Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), p. 9; originally published in 1980 by Éditions du Seuil, Paris, as La chambre claire.

Artwork © Roe Ethridge