Lauren Mahony is a director in the publications department at Gagosian, where she has worked on exhibitions and publications devoted to Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Brice Marden, and David Reed, among artists, since 2012. She previously worked as a curatorial assistant in the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Rob McKeever

Henri Matisse was sixty years old when he embarked on his first major illustrated book, Poésies de Stéphane Mallarmé, inaugurating a new phase in his career during which books became a sustained part of his work. Begun in 1930, Poésies . . . was published in 1932 by Albert Skira, who had invited Matisse to illustrate the volume, a collection of poems first published in 1887. (Skira’s first project of this type, a selection from Ovid’s Metamorphoses illustrated by Pablo Picasso, had appeared in 1931.)

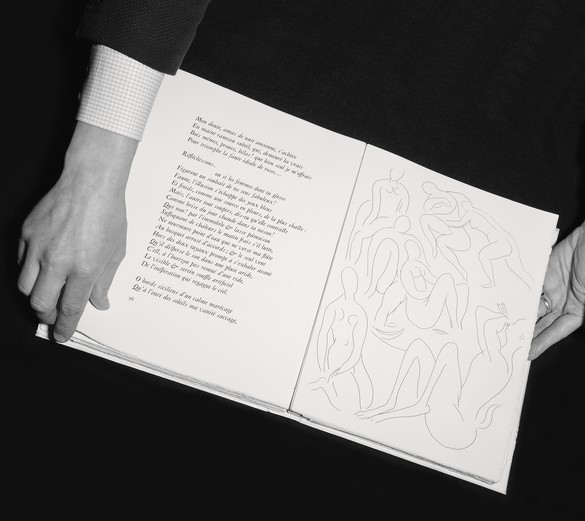

Matisse was fully engaged with the Mallarmé project for nearly two years, concurrent with the large mural on the subject of dance that he was planning for the Barnes Foundation, in Merion, Pennsylvania. Although he had provided illustrations for books earlier on, he had never before been as deeply involved in the overall concept of making a book. Carefully planning the layout and design elements, he made over 200 preparatory drawings, from which he went on to print sixty etchings; twenty-nine were ultimately included in the publication.

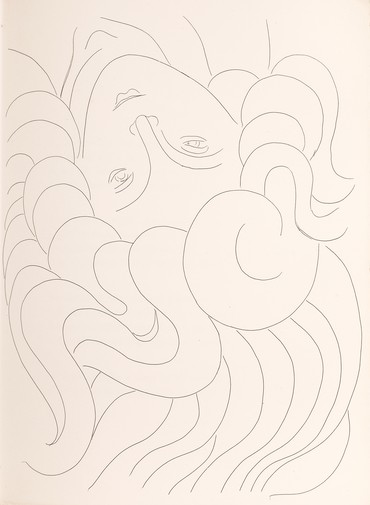

On the challenge of marrying image with text, Matisse would recall in 1946, “The problem was then to balance the two pages—one white, with the etching, the other comparatively black, with the type.”1 To achieve this balance he scaled his drawings to fill the page—a large one, at about thirteen inches tall by nearly ten inches wide—but used thin, minimal lines without shading, leaving the page mostly white. Seeing the book recently at Gagosian, the noted Matisse scholar John Elderfield spoke of the “absolute fluency” of Matisse’s drawing, remarking on the artist’s ability to create areas of greater and lesser luminosity with simple etched lines. Among the wide-ranging subjects depicted in the etchings are Edgar Allan Poe, botanical elements, and Arcadian imagery that recalls both Matisse’s compositions of twenty years prior and the mural-size painting The Dance, simultaneously in process for the Barnes.

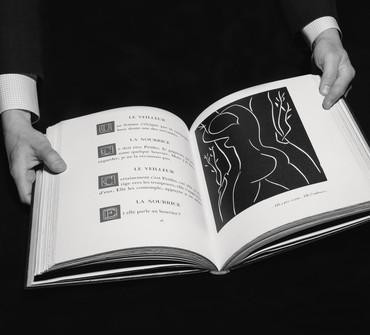

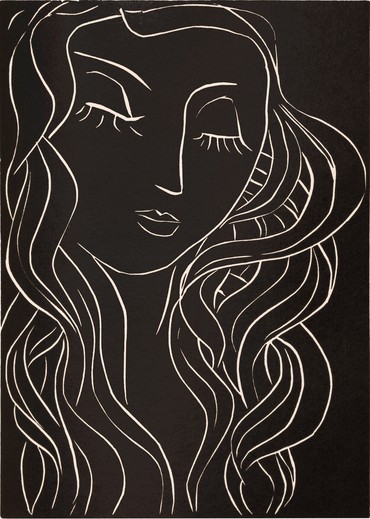

Twelve years later, in 1944, Matisse completed another ambitious illustrated book, this one published by Martin Fabiani, his art dealer during the Second World War.2 Pasiphaé: Chant de Minos (Les Crétois), Henry de Montherlant’s modern interpretation of the classical story, is illustrated with 148 linoleum cuts (the cover, eighty full-page plates, forty-five decorative elements, and eighty-four oversized decorative block letters, printed in red, at the beginning of each paragraph). Pasiphaé marks the first time Matisse used linocut, which creates images drawn in white against a black ground—the opposite effect from the Mallarmé etchings. Riva Castleman, writing in 1978, discussed the balance between image and text, as Matisse had in 1946: “The white lines incised into the black ground of each plate provided a considerably different weight to the illustrations as they opposed pages of text, and the embellishment of the text pages with initials and head and tail pieces deftly offset this imbalance. . . . For the first time purely decorative elements, such as groups of undulating lines, serpentines, and stars, are plucked from their customary positions in Matisse’s compositions and, in the bands above and below, act like traps for the loose blocks of typography.”3 In the second half of the book, a band of stars repeats at the top of several pages; these stars become larger as the reader progresses through the text, as though animated in space.

Each of these livres d’artistes, or artist’s books, is the result of a total collaboration between artist and publisher and each presents a striking pairing of art and literature. Elderfield, who included both the Mallarmé and Pasiphaé in his landmark 1992 Matisse retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, recently remarked, “His very first paintings, made when he was twenty-one, were of piles of books. He was a great reader, who loved books, so it is not surprising that he made great illustrated books. His illustrated books are so integral to his art as a whole.”

1Henri Matisse, “How I Made My Books,” 1946, repr. in Jack D. Flam, Matisse on Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. 167.

2See Riva Castleman’s catalogue entries in John Elderfield, Matisse in the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: the Museum of Modern Art, 1978), pp. 140–42.

3Ibid., p. 142

All artwork © 2017 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY