Alexander Wolf is a director at Gagosian in New York. Since 2013, his projects at the gallery have included exhibitions, communications, and online initiatives. He has written for the Quarterly on Piero Golia, Nam June Paik, Robert Therrien, and other gallery artists.

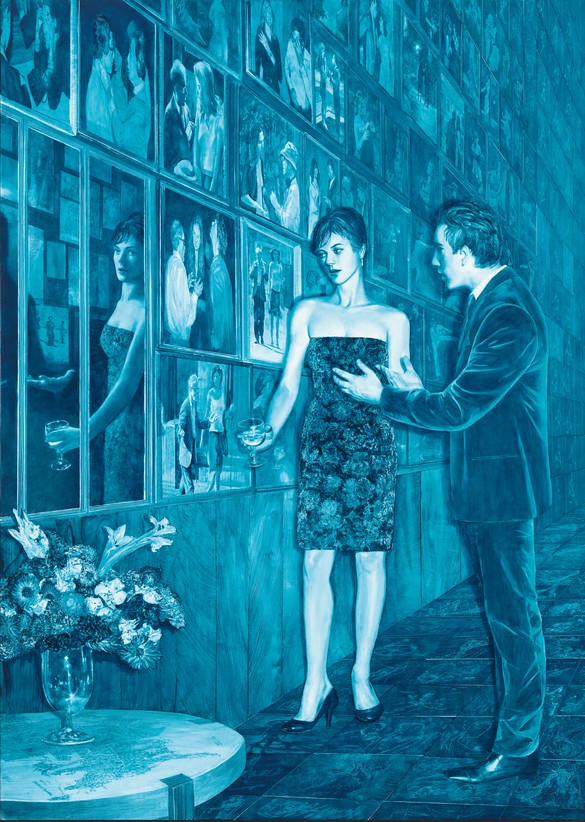

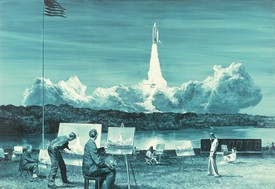

Asked recently whether he paints multiple works at once, Mark Tansey grinned. Reverb, his undivided focus for the last two years, shows a glamorous salon dominated by a long wall of paintings, hung frame to frame, that extends beyond the borders of the 84-by-60-inch canvas. Each square in the grid of floor tiles is inscribed with pictures or diagrams, and mirrors and a vase generate more images still. One work at a time, or many? It remains an open question.

A man and a woman in cocktail attire talk near the wall of paintings. There is tension: he gestures with both hands, making a point, as she looks away into a mirror. Tansey’s paintings are monochromatic, his way of separating borrowed images from their sources and integrating them into a new unity;1 Reverb is in shades of Prussian blue, the color of blueprints.

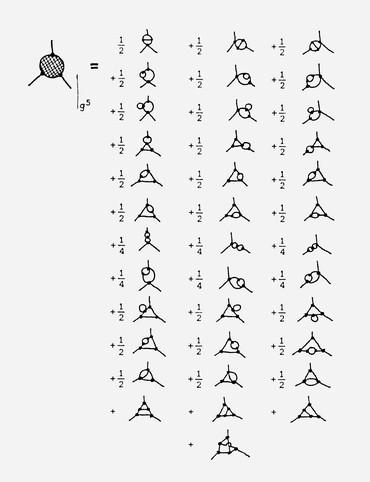

If Tansey’s paintings always reward close inspection, Reverb eagerly invites it. It doesn’t take long to see that several of the framed images show Woody Allen, doing what Woody Allen does: talking and gesturing—making a point, with his words and with his hands. The images of Allen—walking down a street with Debra Messing, with Helen Hunt on the set of The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001), at a party with his collar in the grip of Diana Vreeland—echo the physical and spoken communications between the painting’s central figures. On the wall’s upper right are tiny Feynman diagrams, physicist Richard Feynman’s pictorial representations of the interactions of subatomic particles. Thus the wall holds a survey of pictures of interactions, from infinitesimal ones to encounters between celebrities.

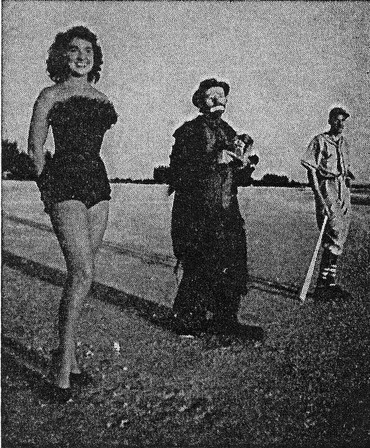

Among other things, Reverb explores the slippage of representation: the fluctuations that inevitably occur when thoughts are illustrated through words and gestures, a face is reflected in a mirror, or life is represented through art. Tansey came of age in New York at the same time as a generation of artists investigating the nature of picture-making, especially with regards to recycled imagery, and he is no exception. But whereas many of his contemporaries—Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, Richard Prince, and others—delight in the shifts of meaning that take place when images are displaced or recontextualized, Tansey also pursues the more immediate shifts intrinsic to common interactions, the changes that happen in the space between the mind and verbal or physical communication. What nuances are lost and gained in translation? Eyeing Reverb’s salon of appropriated images, viewers might wonder what was left uncommunicated in David Cameron’s wave as he left 10 Downing Street for the last time; or by the pantomimes of a vaudeville-era clown.

The nature of Tansey’s inquiry can be traced in part to his variegated studies at New York’s Hunter College in 1974–78, where he made some of his first forays into image-morphing in courses taught by Ron Gorchov and Robert Morris while also sitting in on Rosalind Krauss’s classes on the French semiologists. Merging these interests, he created notebooks of book and magazine clippings picturing people in every conceivable position—an encyclopedia of human gestures.2 Intense acts of cataloguing have played a role in his process ever since. Nor are images his only sources: it’s possible that more of his preparatory materials derive from literature and language. A note in his current workbook suggests we consider the title Reverb not only in terms of its many visual echoes, but also verbally:

Rereading

Reseeing

Resignifying

Reenacting

Rerealizing

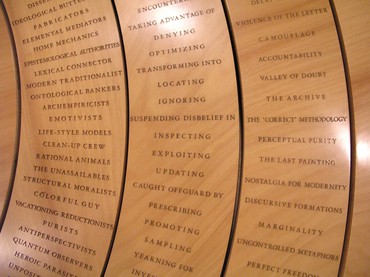

At Tansey’s recent one-painting exhibition at Gagosian, Reverb was accompanied only by Wheel (1990), a wooden tablelike apparatus whose top comprises three concentric circles inscribed with words. The circles divide loosely into subjects, verbs, and objects, though some entries may be fairly lengthy phrases. These circles can be turned, and as they spin, the words align in countless combinations—“something I used against artist’s block to provide narrative,” Tansey has said.3 A spin of Wheel might tell us “modern traditionalist stalled by sea change,” or “cubists on the threshold of delay tactics.” Tansey’s inclusion of Wheel in the exhibition is telling; he once wrote of this functional sculpture, “I’ve found it useful in making it possible to mix distinctly different levels of content: the conceptual, the figural, and the formal, much as one mixes red, yellow, and blue on a color wheel.”4 (Indeed, the sculpture was predated by several paper versions that he actually called “color wheels.”) Language is to Tansey what color is to most painters—he has referred to his work as “pictorial rhetoric.”5

Picture a deck of cards based on eye-mind-hand interactions and contradictions. To play the game, select some cards, shuffle them, and continue by finding analogies. You make the cards as you go. Sometimes new features or behaviors emerge. Sometimes it might seem as though the deck is infinite.

Mark Tansey

If Wheel has become something of a symbol of Tansey’s atypical process, Reverb may be the painting that epitomizes his ability to hold viewers through gradual revelation. He describes the work as “the space where thinking, seeing, and making interact simultaneously and sequentially.”6

The image fuses impressions of the studio, of an archive, of a blueprint (hence the Prussian blue), of a cocktail lounge, even of a church, complete with icons that constitute a layered narrative. A side table bearing a resemblance to Wheel alludes to Tansey’s creative past, while the sketches, diagrams, and tracings on the floor may evolve into future paintings—monochromatic, surely, but colored by the wide spectrum of his purview.

1See Arthur C. Danto and Mark Tansey, Mark Tansey: Visions and Revisions (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), p. 128.

2See Patterson Sims, Mark Tansey: Art and Source (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1990), p. 8.

3Tansey, quoted in Phoebe Hoban, “The Wheel Turns: Painting Paintings about Painting,” New York Times, April 27, 1997, available online at www.nytimes.com/1997/04/27/arts/the-wheel-turns-painting-paintings-about-painting.html (accessed March 13, 2017).

4Judi Freeman, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Tansey, Mark Tansey (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993), pp. 69–70.

5Tansey, quoted in Hoban, “The Wheel Turns: Painting Paintings about Painting.”

6Tansey, telephone conversation and email exchange with Amanda Hajjar of Gagosian, March 8 and 9, 2017.

Artwork © Mark Tansey