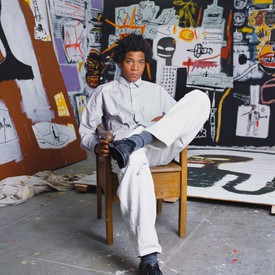

Torkom Demirjian is the founder and chairman of the family-run Ariadne Galleries, with locations in New York and London and specializing in the art of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, the Near East, Greece, Rome, Asia, and early medieval Europe. In 2015 he assumed the role of chairman of the board of the Hermitage Museum Foundation. Photo: courtesy Hermitage Museum Foundation

Dr. Mikhail B. Piotrovsky is a professor at St. Petersburg State University and has served as the director of the State Hermitage Museum since 1992. He is the son of Boris B. Piotrovsky, the director of the museum from 1964 to 1990. Dr. Piotrovsky graduated with honors from the Oriental Faculty of Leningrad State University in 1967, specializing in Arabic Studies, as well as attending Cairo University from 1965 to 1966. He studied and worked at the Leningrad branch of the Institute for Oriental Studies from 1967 until 1991, before joining the Hermitage. Photo: courtesy State Hermitage Museum

Torkom Demirjian You’ve just seen the Richard Serra exhibitions at Gagosian in London and New York. Recently you invited Richard to have a show at the Hermitage and you were able to meet him to discuss it. What are your feelings after the meeting?

Mikhail PiotrovskyI feel that we have a good beginning. Now that I better understand the juxtaposition of paper and steel, we know what to present to our exhibition committees. I also now understand how we can play with our space. We have new spaces that are very big and beautiful and demand special kinds of exhibitions. We have a lot to do, but I feel that we can propose interesting solutions for the big spaces that we have. For instance, our hall is covered in four stories of courtyards. We are hoping that this space interested Richard enough that he might do something special for it. It’s wonderful to be working with such an amazing artist who can push us to be innovative from the point of view of museology.

TDFor seventy years, the Hermitage was not acquiring much American art. Now you seem deeply interested in acquiring work by American artists and you have so much space available to you. What are your hopes for the future?

MPIt’s not exactly true that we didn’t acquire American art, we were just acquiring it slowly. At this point, though, there’s a lot of American art that we need to acquire. Today one of the main goals of the Hermitage Museum Foundation is to provide the Hermitage with a more comprehensive selection of American art. Twenty years ago the Foundation’s focus was the restoration of the Hermitage buildings; now it’s more focused on expanding the collection. We recently received through the Foundation, for example, a gift of American decorative art from the postwar period. It’s an incredible acquisition and works very well in the new building. It is a great example of the Foundation’s success, but we need to show American art in all of its varieties.

TDHow does it feel that, among the most prestigious museums around the world, you are the longest-serving director?

MPWell, to me there’s a big difference between our museum and any other museum in the world. Most museums are places where people work, and they can do great things, but the Hermitage is a place where you live. When you join the Hermitage you’re not planning ever to leave it. It is a very special museum. A Hermitage curator is not planning to move on to any other museum later in his or her career. That’s a very important feature of the Hermitage, that it’s a museum for life.

TDThat’s wonderful. So how does a gallery like Gagosian fit into that? What are the future collaborations that the Hermitage can do with a gallery of such depth?

MPWe’ve worked with Gagosian several times over the years, on exhibitions of Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly, and others. So this won’t be the first time we’ve worked together, and those earlier experiences are important—especially in Russia, where relations between museums and galleries are not a simple thing. Without getting too specific, it can be difficult to build quality relationships with galleries in Russia, so it’s critical for us to also have wonderful relationships with influential galleries elsewhere. We also need to learn the systems, to know how museums and art markets interrelate, where we can complement each other and work together. American institutions and art galleries do this well, and finding this balance is very important. I see this opportunity with Gagosian as a way we can learn and take the next steps in Russia. Richard’s exhibition will be a wonderful collaboration.

TDOne of Gagosian’s most notable accomplishments is that so many of the shows it organizes are on par with museum shows, it does very serious work. Its catalogues are equally valuable. And something that’s not widely known, but that I have experienced, is that Larry Gagosian is very philanthropic, although he does that work anonymously. How can we make the best of Larry and his philanthropic leanings?

MPWell, that’s your job as chairman of the Hermitage Museum Foundation! [laughs] But you’re absolutely right, the shows are wonderful and the books are at the highest level. As a museum director, though, we still have to maintain the difference between gallery shows and museum shows. Gallery shows need a sense of discovery—they can be a little more risky than museum shows, and most often they present new work. It is only between those shows that they can host blockbuster exhibitions primarily for the general public. Museum shows must all be of high quality as a standard. But quality museum style and quality gallery style, while they’re a little different, both make the world much more interesting.

TD Gagosian has an impressive history, with many important artists, and it represents estates and foundations as well. What do you hope this access might bring to the Hermitage?

Art belongs to the world.

Dr. Mikhail Piotrovsky

MP It’s an amazing list, and there are many artists who will be new and important for our audience.

TD How do you respond when people say that the current political climate between Russia and America is tense? Why is it important for the Hermitage to get the support of the American philanthropic community, art lovers, and artists?

MP This is not the first time the politics between Russia and America have been tense. In recent history alone we saw the Cold War, then a period when we were able to live in shared trust, and now we have a period of mistrust again. So cultural institutions, especially in Russia, know how to deal with this. And actually, seeing the political landscape shift so often just emphasizes how important and enduring culture is—it helps us to understand that strong cultural ties and collaborative cultural relations are above politics. In politics and the economy, problems come up quickly and can often be quickly solved. Cultural relations, if you destroy them, are very difficult to rebuild. We should use every opportunity to emphasize that supporting cultural connections now can have a positive effect in the long term.

TD I have always seen culture as the only sustainable way to overcome all kinds of difficulties.

MPAbsolutely.

TDAnd Americans are probably the most philanthropic people on the face of the earth, maybe in human history. What we do here we hope will somehow begin to have an influence on the new and emerging wealthy class in Russia, so they can see the benefits of emulating this American tradition.

MPThat’s exactly what happens. When we first began to have sponsors and donors they were all foreigners, but we were able to use their generosity to convince our own government to give money too. When our politicians saw that people outside Russia were willing to contribute, and that we could be responsible with those gifts and could have a positive impact, they began to contribute as well. At the same time, we educated our wealthy class with examples of what we could do, and now we have a lot of private Russian donors. Historically, Russian institutions were mainly supported by foreign and American foundations. In Russia today it’s more often Russian money.

Cultural relations, if you destroy them, are very difficult to rebuild. We should use every opportunity to emphasize that supporting cultural connections now can have a positive effect in the long term.

Dr. Mikhail Piotrovsky

TDThat’s because Russians are now taking pride in sustaining institutions that are important for Russia.

MPYes, and they’re beginning to understand that cultural institutions are important for future generations, as well as for their other businesses.

TDIn today’s world it can be difficult to distinguish between socioeconomic, political, geopolitical, and cultural goals. I’m thinking about the destruction that is occurring on many of the world’s cultural-heritage sites—I know that you at the Hermitage have been outspoken on this topic and have taken many initiatives to address it. What are your feelings on this issue? How do you approach it without politicizing it, as opposed to contributing positively?

MPIn the current political climate, when culture faces such immediate dangers, we must be present. We must explain that culture is incredibly important, that it has its own rights, and that its rights can often be more impactful in the long term than the rights of states. We cannot simply say, “Oh, it’s terrible what happened,” we have to generate ideas about what can be done to prevent it. One crucial need, in my opinion, is that cultural objects must be protected, by force when necessary. And when they are destroyed, or half-destroyed, we must restore them. A while ago there was a UNESCO committee in St. Petersburg dealing with this—some shrines were destroyed in Timbuktu and the committee made a big announcement about how terrible it was. The very next day after hearing that announcement, the people in Timbuktu came back and destroyed more shrines. So just saying “It’s wrong” doesn’t work. You have to have a plan, and you have to share that plan with the relevant governments, show them a better way, make sure they understand how important these things are. They won’t listen always but they will sometimes.

TDIn the academic world, sovereign rights are seen as more important than culture itself. So individual initiatives among people of good will are often discounted, and many of the objects you’re talking about have been orphaned. Nobody seems to understand that the cultural well-being of these orphaned objects typically falls more on individual private initiatives than on governments, or even on government controls. Yet government controls aren’t really enforced, and individual initiatives often aren’t welcome because people think someone offering help has other motives, perhaps is secretly a collector of these things. What is often overlooked is the fact that collectors are often the great protectors of these objects.

Most museums are places where people work, and they can do great things, but the Hermitage is a place where you live.

Dr. Mikhail Piotrovsky

MPWe’ve had some similar travails. Just think about all the recent destruction in the Middle East and all over the world. But if you try to move objects as a way to protect them, there’s that old story about the “terrible” European nations who “robbed” poorer countries, moved their cultural possessions to European museums, and then had to give those things back. Well, thank God we have Babylon in Berlin, and Nineveh in the British Museum, because Babylon and Nineveh themselves were destroyed. I hope that examples like this can help people see that objects in museums are there to be shared with the world, for the future, and that institutions preserve admired objects and allow scholars to study them. And spreading objects around is a safe way of protecting culture—spread things around a little and one bomb won’t be able to destroy a whole heritage. If you collected all the Armenian manuscripts and gathered them in one place, then one bomb and that entire heritage would be gone. That’s a vulnerability. As such, the spreading of knowledge and the dissemination of art are good things.

TDOne argument is that allowing museums to collect artworks from distant cultures, diversifying or spreading them around, enhances the value of those objects. Many people think that enhanced values cause more destruction. I’ve always argued the opposite, saying enhanced value actually protects culture.

MPIt can be argued both ways. Museums, for instance, actually explained ancient Greek culture to the world, and showed why it was so important and had to be presented and preserved. People need to understand that there are objects around them that have to be protected, and it falls on museums to explain that. If people focus too much on values or prices, they begin to think of art as property. Art is certainly bought and sold at certain moments, but its ownership is not restricted. Art belongs to the world.

TDWhether Greek art is in Greece, New York, Berlin, at the Hermitage, or in the British Museum, it is still Greek art. Bringing Greek art to the Hermitage doesn’t turn it into Russian art, and at the British Museum it’s not British art; it’s still Greek art—a credit to Greek civilization and to the people who created these incredible things.

MPPartly right and partly not. We present Greek culture but we don’t re-create the experience of seeing it in Greece. The sculptures we show at the museum are not presented against the columns of ancient Greek architecture, they have become part of world civilization. At the Hermitage we have Rembrandts that have been there for two or three hundred years, and we call them Russian Rembrandts. The Matisses in the Hermitage are Matisses of France but also Matisses of the Hermitage, because they live there. This diversity—not difference but diversity— makes the world interesting: we’ve organized a diversity of cultures.