Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

It has long been beyond doubt that Henri Matisse is one of the giants of European modernism, a quintessential bridge between the art of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. But what if Matisse’s work is considered more directly through the eyes of the American artists he influenced? What if Matisse could equally be described as a bridge between European and American artists? Matisse and American Art at the Montclair Art Museum examines this transatlantic exchange for the first time, revealing that Matisse’s place in art history owes a debt to his relationships with American artists, collectors, and curators, as well as examining the sizable influence Matisse’s work had on early modernist, midcentury, and contemporary American artists as diverse as Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and John Baldessari.

Not only does Matisse and American Art complicate the matrix of influence usually associated with Matisse—a lineage that includes Ingres, Cézanne, and Monet—but it also offers an alternative timeline for American art. The prevailing narrative is that American art only achieved international significance with the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s. However, as the exhibition’s curator Gail Stavitsky explained, this show rescues early twentieth-century American art from the shadow of the European avant-garde, shedding light on an overlooked dialogue that shaped the course of modern art as we know it.

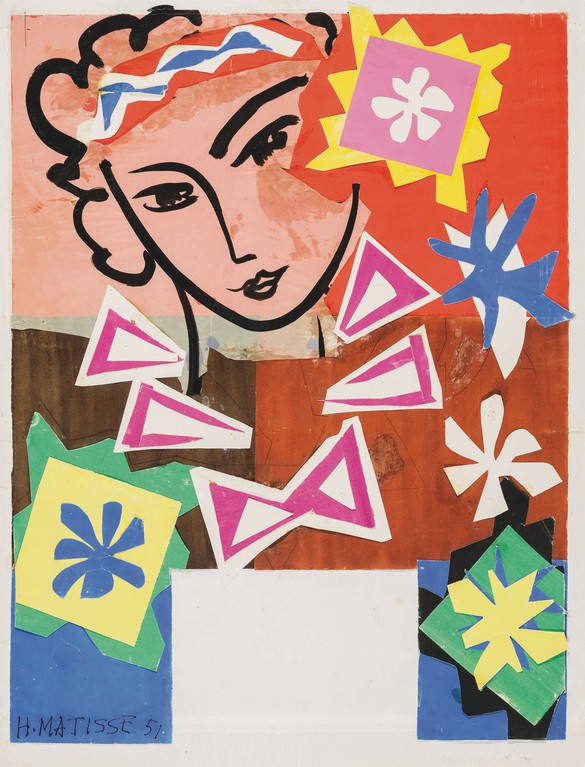

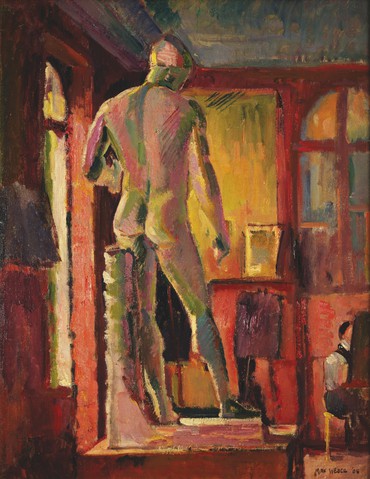

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are met with some of the earliest Matisse works to be shown in the US, including Le Grand Bois (The Large Woodcut) (1906). These are presented alongside works by his students Max Weber and Sarah Stein, some surprising paintings and drawings by Arthur Dove and Maurice Prendergast, and a quilt by Faith Ringgold. So it’s immediately clear that the show is not simply about American artists making direct reference to Matisse—it also follows the ways that American artists adapted his innovations for themselves and how their interpretations offer new ways of viewing Matisse. Even Weber, who was a student at the short-lived Académie Matisse, displays a unique style that is related to his teacher’s work without mimicking it. The pale pinks and greens in Weber’s Apollo in Matisse’s Studio (1908) come alive, reflecting those in Matisse’s Nude in a Wood (1906). A vitrine displays several open sketchbooks, one featuring Prendergast’s rough drawing of Matisse’s Nasturtiums with the Painting ‘Dance’ I (1912).

The Académie Matisse gets something of its due here as well. Opened in 1908 in Paris, the school counted among its American students Patrick Henry Bruce, Arthur B. Carles, Henry Lyman Saÿen, Morgan Russell, Sarah Stein, and Weber. Though the school remained open only until 1911, the relationships that formed there (and at Gertrude Stein’s famous apartment on rue de Fleurus) had far-reaching effects. Back home in the US, Matisse’s American students not only made people aware of his work by adopting elements of his style, many of them physically brought Matisse’s work home too. “They appreciated and adapted Matisse’s work, but they played a role in disseminating the work as well,” Stavitsky said.

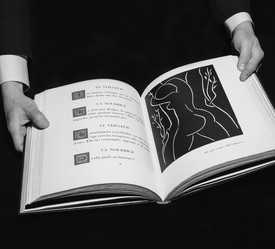

Still, Matisse’s rise to popularity in the US was not meteoric. His first solo exhibition in New York (at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery) in 1908 received negative reviews. Five years later, seventeen Matisse works were included in the 1913 Armory Show, at a critical moment, as New York itself was becoming intertwined with the course of modernism. Matisse’s reputation grew steadily over the next decade. In 1930, he was featured on the cover of Time. (A copy of the magazine is featured in an archival section of the Montclair exhibition.) And in 1931, Matisse was the subject of the Museum of Modern Art’s first monographic exhibition, organized by its founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., whose continued advocacy of Matisse (organizing a larger retrospective, and authoring a substantial monograph in 1951) solidified Matisse’s relevance to a younger generation—right as the New York art scene was on its way to replace Paris as the art capital of the world.

Matisse appropriated classical themes—the nude, the still life, the pastorale—but he reinvented and often subverted them with the musical energies of his audacious color. Having rejected the formal tropes of the Old Master canon, Matisse’s forms could more easily be used for other purposes. For instance, in Matisse and American Art, the jazz cut-outs hang across from paintings by Tom Wesselmann and Roy Lichtenstein, aligning Matisse’s interest in patterns and textiles with American Pop art. Suddenly, a new mental link forms between Matisse and the Ben-Day dots of Lichtenstein’s Bellagio Hotel Mural: Still Life with Reclining Nude (Study) (1997), which also depicts a Matisse sculpture.

Even the Abstract Expressionist and Color Field works in the show challenge the usual Matisse narrative. Matisse’s Pianist and Checker Players (1924), for example, a detail-packed interior scene, is bracketed by two fields of deep red: a 2002 painting by Helen Frankenthaler, and No. 44 (Two Darks in Red) (1955) by Mark Rothko. The reds of course evoke Matisse’s Red Studio (1911), yet here they accentuate the red details of the wallpaper and textiles in Pianist and Checker Players. Meanwhile, Woman in Blue (After Matisse) (1985) reveals Andy Warhol’s ability to capture the essence of Matisse’s linework, yet the silkscreening process makes Matisse infinitely reproducible, bringing the French artist into the commercial realm. John Baldessari’s Eight Soups (2012) continues this arc of influence; he conflates the style and subject matter of the two celebrity masters, screen-printing Matisse’s iconic goldfish bowl in various colors, simultaneously alluding to Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans. This, alongside Lichtenstein’s 1978 sculpture of the same fish bowl, is a striking example of how American artists have expanded Matisse’s place in history: Matisse arrived on the scene as a window into the European avant-garde, but along the way was transformed for a uniquely American cause, becoming a vital foundation for contemporary art.

Matisse and American Art, on view at the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey February 5–June 18, 2017, includes two related exhibitions. Inspired by Matisse, which highlights works from the Montclair’s impressive collection, and Janet Taylor Pickett: The Matisse Series, featuring recent collages and handmade books that reveal the influence of Matisse on Pickett’s oeuvre.