Katy Siegel is the Thaw Endowed Chair at Stony Brook University and senior research curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Her exhibitions include Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, and High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967–75. She is the author of Since ’45: America and the Making of Contemporary Art.

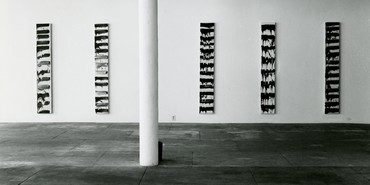

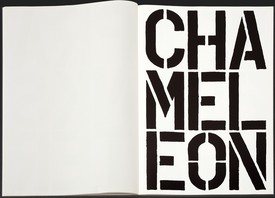

Christopher Wool may be best known for his paintings of large, black, stenciled letters on white canvases, but he actually works in a wide range of styles and with an array of painterly techniques, including spray painting, hand painting, and screen printing. Wool’s work sets up tensions between painting and erasing, gesture and removal, depth and flatness. He was born in 1955 in Chicago and lives and works in New York. Photo: Aubrey Mayer

Katy SiegelHow did you react, Christopher, when you saw David Reed’s brushstroke paintings at Susan Caldwell’s gallery on West Broadway in 1975?

Christopher WoolIt was somehow an important show when I saw it. It’s stuck with me for a long time. The paintings haven’t been shown much since then so I’ve always wanted to see them again. I was at the New York Studio School for one year, fall 1973 through spring 1974, and I must have known about David, he’d been at the school before me and was considered a founding student. I was nineteen years old, just starting to see shows, when I saw that show.

KSSo why did it stay with you all this time?

CWI thought they were extraordinary paintings. Now that we’ve been able to see them again, that’s not a misremembering—they’re very strong. They also capture something for me—going through all this, I think you and I have discovered that they were quite unique in a certain way. David was investigating certain Post-Minimalist things that were of the moment for sculptors but that not so many painters were able to address: the idea of process becoming image. I guess the one painter who would stand out in that respect would be Robert Ryman, but David took it a big step beyond, I think, and with more of an emphasis on the process part. The other artist I think was close was Cy Twombly, his blackboard paintings.

KSIf you were describing the work to someone who hadn’t seen it, what would you say was so strong about it?

CWWhat’s great about the paintings is that they are a visualization of how to both make and read a painting. You start in the upper left and then go left to right and top to bottom, the way you read a book. Twombly’s blackboard paintings are composed somewhat similarly (and of course have their own reference to writing).

KSPeople say that so often about Twombly but I’ve never thought about it with David.

CWWith him it’s not so much a reference to writing, it’s like, if you’re going to cover a canvas, how do you do it in the most economical or least compositional way?

with “Autumn Rhythm,” Pollock allowed the form to emerge out of the materials and out of the process. For me, as a student, this idea of allowing the form to emerge out of the process was incredibly important.

Richard Serra

KSSo, two things: first, this makes me think of your word paintings, which I had never thought about that way, in terms of the relationship between the way you cover a painting and reading and writing.

CWI hadn’t thought of that, but I guess it’s true. When I was doing those paintings, especially at first, I was trying to avoid pictorial composition. As paintings they were written rather than composed.

KSAnd you solved the famous problem of the corners—how to make them part of the composition, or whether to ignore them completely.

CWI don’t know if I solved it but I avoided it. Clement Greenberg would have been aghast.

KSThe second thing is that a lot of artists from that time talk about making work in a sort of working class, hand-labor kind of way, like laying bricks or tile—making work in a really practical way instead of composing.

CWThat was particularly true for sculptors working with the idea of truth to materials. Painters didn’t really have an equivalent for the kinds of industrial materials that sculptors were working with.

KSBoth Vija Celmins and Chuck Close, though, working around the same time, have talked about building their compositions brick by brick. Did that appeal to you, that interest in making something that wasn’t fussy or pretentious or arty?

CWOh yes, of course.

KSWhere did that come from for you, do you think, that sort of horror of fussiness? You’re much younger than those artists.

CWWell, I’m naturally fussy, much to my own horror. Fussiness kills, and the Reed paintings are a great example of an artist refusing to be fussy, which of course creates all this pictorial tension that’s so much a part of this work.

KSYou’d only just come to New York—were you aware of things like “This person’s a third-generation Ab-Ex, this person’s Color Field, this is another kind of artist”?

CWYes, I think so. I read art magazines, mostly old ones. I was learning quickly. It’s the art world, not rocket science.

KSI don’t think of this as a great time for expressiveness, so I wondered if David’s paintings looked expressive to you as well as literal and materialist.

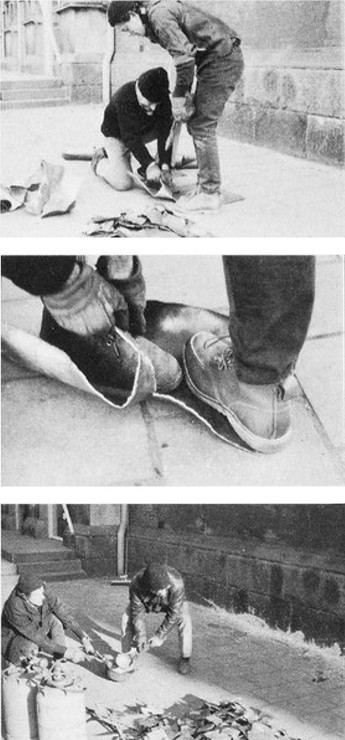

CWThey did, but I don’t think the issue of expressionism was so important at that time. And formalism was also something to avoid—“Kill the corners.” That’s what was great, those paintings had both. I think that’s what people were seeing in them. That’s what I saw in them—they were some of the ideas that painters might have been thinking of but he was also capturing what some of the sculptors were doing in terms of process, someone like Barry Le Va, or Richard Serra with his thrown-lead pieces. Would you use the word “expressive” in talking about Serra’s thrown-lead piece?

KSI think people don’t, but maybe we should.

CWI think I do. It’s a step beyond Jackson Pollock in terms of getting away from image, but it’s still expressive in the same kind of way.

KSOne thing I’ve always been interested in is how wrong art history gets the relationship between Abstract Expressionism and later artists. There were lots of things about the Abstract Expressionists that bothered or embarrassed younger artists—overheated rhetoric or what seemed like ego or whatever—but it’s so interesting to look at the notes of Richard Pousette-Dart, whom you studied with, and see how much they’re about the experience, the journey, the voyage.

CWOh my God. There was no one quite like Pousette-Dart. He believed that the experience of making a painting was more important than the painting itself. That’s a different notion of process from what the Post-Minimalists were doing, but it is again a focus on the act of making a painting as opposed to the image. So is that then “expressionism”?

KSI think people forget how much the Abstract Expressionists were interested in the experience rather than in something finished. That sort of hardening of signature style came later.

CWYes. From Pousette-Dart and the New York School to Serra and the thrown-lead pieces, a lot of art is talked about as one generation rejecting another and moving on. I think it’s more of a continuation.

KSMaybe that’s something you can see better from a distance. When you’re right in the moment, all you see is how you’re different from the people a little older than you, but from a distance you see continuity and similarity.

CWI think David has spoken about Pollock, Pollock was important to him. I don’t know what Serra feels about the throwing-lead piece and Pollock—I would assume he acknowledges a connection.

KSYes, Serra has said that the idea that the form in a painting like Autumn Rhythm came out of the process was important to him as a student. The difference might be that the rhetoric around sculpture like Serra’s is that it’s antiexpressive, it’s to do with pure material and a kind of impersonal action, whereas the rhetoric around Abstract Expressionism and that older New York School is more personal, it’s an expressiveness that includes emotions as well as physical feelings.

CWI guess I would agree with that, but probably less than what it felt like at the time. If you look back at David’s 1975 paintings or the thrown-lead piece, they seem less different from their predecessors than they might have back then.

KSLooking at those paintings, now that we’re looking back, do you see a lot of variation in the work? Does each painting look individual?

CWYes.

KSDoes it look serial?

CWIt was a consistent body of work, but I don’t think serial. David was even changing the color of the white background, and doing many more experimental things than you realize at first. There may have been a little feeling of seriality, though, in the fact that they were either red or black and that he combined them in the show. I think that was a typical Post-Minimalist strategy.

KSTo reduce the number of factors.

CWYes, for sure, and exactly what David did so successfully in these works: he reduced color to monochrome, reduced illusion and pentimenti, and made composition nonpictorial by literally covering the canvas.

KSSo the thing that came out most was the variation in the material and how it behaved in different paintings.

CWYes, the process of making the paintings was the subject of the paintings and the materials had to be handled appropriately. But ultimately these paintings are pictures as well. I was aware of that right from the beginning, and that’s what was exciting. The Studio School was really about painting as pictures, so I would guess that was its influence on David. The idea that focusing on process could be the way you create a picture became quite important to me.

The problem for me is always when it goes to all image or all process. Those extremes interest me less than the places where they come together. One of the most interesting things for me in talking to you has been the very specific way you talk about process.

Katy Siegel

KSWhat is it about that that’s important to you?

CWThat’s difficult to answer because it seems so obvious to me. . . . the fact that you can make a picture without trying to make a picture seemed very liberating. I guess it’s a picture-making strategy for an abstract painter. To rely on process is to make a painting without relying on the usual formal considerations that were supposed to define a successful painting. You’re making a painting by pretending you’re not, in a way, though pretending isn’t the right word.

KSDo you fool yourself?

CWSometimes I try … It’s not about fooling, though, it’s just about focusing on something else. I would have a painting with certain elements and I would paint over the black images in pink, say, and that would create a shape, a shape created not out of compositional necessity but simply out of the process of overpainting the image, and that shape would become its own picture. It could only be that picture by going through that particular process. I think David’s the same. He had this idea of horizontal brushstrokes covering the canvas from left to right, and that became a kind of action picture.

KSIn response to the same question, the Pop artists say, “We don’t want to worry about what to paint so we’re just going to pick these stupid figurative things and copy them.”

CWYes, that’s a similar strategy in a way. I don’t like the word “strategy” but that’s a strategy to make a painting without caring about a certain part of traditional painting. David was doing something similar but with a different set of factors. And here I find similarities to what Josh Smith has achieved with his name paintings and his palette paintings and Wade Guyton with his use of the inkjet printer.

KSMaybe that’s a continual problem after the 1940s: how do you make a picture when there’s nothing you have to do? Barnett Newman said something like, “We make pictures without relying on any known shape. We don’t use geometry, and we’re not European, so this is a metaphysical act, because we have to make it all up from ourselves.” So without a theory (which all of those people were against), and without an academic set of standards, what do you do? Relying on materials, or setting up a situation, or saying that action is enough, are ways to go.

CWYes, and Andy Warhol asked Brigid Polk, “What should I paint?” He wanted other people—

KS—someone else to tell him.

CWYes, and that was his liberation. I think it’s similar, and I think it’s a post–New York School thing.

KSDespite that continuity, though, it feels to me like you and David are right on the cusp, an intermediate moment. The painters five years older than you I don’t think contact that, and I feel like you do.

CWIt’s hard to pinpoint but yes, I think we were the cusp generation. That year of 1975 is shortly before this quite particular moment when postmodernist thinking and examination start.

KSI feel strongly that David’s paintings in that show were not just the end of something but the beginning of something. You can see that in the painting he showed in the 1975 Whitney Biennial: this is a single painting with two panels and the second is a version of the first. So the first canvas is process that becomes a picture and the second one is almost all picture, or at least a very different kind of process—remembering rather than inventing.

CWExactly. Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum I and . . . II [1957] play with that relationship, as do a lot of works by Jasper Johns.

KSAround the same time, in the mid-to-late ’70s, Jack Goldstein is making his early films like Shane and The Jump, which take an action that turns into an image and repeat it over and over again. And the mid-’70s are when Cindy Sherman is starting in Buffalo. I feel like David belongs to that context as well, there’s a connection to the early Pictures Generation.

CWI did not see the Pictures show [at Artists Space, New York, in 1977, curated by Douglas Crimp] but I was starting to be aware of some of those artists. There were different aspects in what was developing in postmodernist thought at that time. One had to do with narrative and pictures and real life; that was not where my interest lay. The part that was important to me was the notion that the modernist idea of the masterpiece was either no longer possible or no longer necessarily an objective. Where the Abstract Expressionists had still been wedded to the modernist concept of the masterpiece, the postmodernists suggested that there were alternative ideals and possibilities to the Greenbergian idea of the perfect painting. I think in a way those artists were expanding on something that was already there in Post-Minimalism.

KSThe difference is that with the artworks that are considered Post-Minimalist, like the work in Anti-Illusion [at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 1969, curated by Marcia Tucker and James Monte], those artists really aren’t so interested in image. And the thing that what people used to call postmodernism adds is that while, yes, there’s the sense of the antimasterpiece, there’s also an interest in imagery.

CWIt actually went further: there were many who ruled out abstraction. When they talked about painting, it was about painting as picture. Abstract painting was not thought to offer any possibilities.

KSWithout belaboring that “end of painting,” I guess one of the things that interest me about that work of David’s, and it’s the same thing I see in yours, is that it holds together the abstract and the pictorial, the process and the image, in a way that I also see in Georg Baselitz and other people.

CWOr Sigmar Polke’s ’60s paintings.

KSThe problem for me is always when it goes to all image or all process. Those extremes interest me less than the places where they come together. One of the most interesting things for me in talking to you has been the very specific way you talk about process. Most people talk about it as if it’s one thing, a single choice or way of working, a monolithic preference, as opposed to, say, representation or concept.

CWProbably because they haven’t made paintings.

KSDavid loved the work and he loved the materiality in the Anti-Illusion show, but he was ambivalent about the critique of illusion, the fantasy that you can do away with illusion altogether. He wanted to remain entirely in the present moment and the act, but he always felt split, seeing himself from the outside, seeing the painting as an image.

CWThat’s interesting. I suspect I’m just enough younger than David that I don’t remember being forced to think about illusion or illusionism. Or more likely I probably simply didn’t understand the issue in its full complexity.

KSSo you never had to get over it?

CWNo. Can’t get over it if you don’t get it in the first place. And it’s one thing for a sculptor to be anti-illusion, it’s a little different for a painter. Are David’s 1975 paintings anti-illusionist?

KSIn those works he tries to get rid of illusion, to be entirely materialist, and fails. And that’s what those paintings were for him, realizing, “I’m going to try to do what they’re doing,” but the gap always opens up.

CWMaybe we’re back to the modernist/postmodernist idea. Postmodernism reminded everyone that there are no absolutes, and that the modernist idea of the absolute was ridiculous in the end. There were no perfect paintings. What was dying was the idea of the masterpiece, not painting as a practice.

KSWhen I learned this material in grad school what seemed strange to me was, it was a critique of abstraction at a time when so many of the abstract artists of older generations were already completely aware of the problems of academicism and repeatability and style.

CWAnd of course there were New York school artists who were already on paths outside of modernist prescriptions—Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman, and again Pousette-Dart.

KSYes. As early as 1952 Harold Rosenberg warned that signature styles turn into trademarks, and I feel like Pop art comes out of that awareness that Ab-Ex turned into habits. So I think people were aware of it early on. Habit is a problem for everyone who lives long enough.