Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

HANS ULRICH OBRISTHow did this all begin?

BRET EASTON ELLISWell, I lived in New York for many years, and when I came back to Los Angeles—this was roughly around 2006—I was shocked by the burgeoning LA art scene. It was very different than it had been when I left, there were more galleries, and a real sense that something was happening. And I found myself being invited to certain dinners and art openings, so I met a lot of gallerists and artists, including Alex. I was interested in his work, so we became friendly.

ALEX ISRAELAs a big fan of Bret’s work for a long time, I was excited to meet him and to interview him for Purple Fashion magazine when I was in graduate school. Bret was a subject on As It Lays, which is an artwork [talk show] of mine, and then we just kind of became friends. So, I asked him if he wanted to do a series of paintings with me.

BEEWell, you invited me to dinner at the mall, how could I say no? [laughter] Although the Beverly Center is a nice mall.

HUOAlex, you once told me that as a teenager you were inspired by Bret’s work. Maybe you can talk about the impact it had on you and which books inspired you.

AIWell, all of them. The first one I read was Less Than Zero; I read it on the airplane coming home for the holidays during my freshman year of college. And that’s exactly what the main character in the book is doing. So I felt an immediate connection. The book goes on to describe Westwood Village in the 1980s, which is where and when I grew up. So even though I hadn’t met him at that point, I felt as though Bret was a kindred spirit.

HUOBret, can you describe the genesis of Less Than Zero? Was there an epiphany, or how did you come to write the book?

BEEIt’s crazy, but I was interested in novels as a very young kid, like at seven, eight, nine—not just young adult novels, but books my mom bought. So I wrote a novel when I was fourteen. It was about my experiences—I had done very badly in school, and instead of going to summer school, my parents sent me to a relative’s cheap hotel up in Elko, Nevada, where I worked as a busboy for the summer. And I wrote about that. That was my first novel. At around fifteen or sixteen, I began to make notes for Less Than Zero. It was based on diary entries—it was very journalistic. It was about experiencing LA as a teen in the early 1980s. The book took many forms before it was finally published, but its roots were journalistic and very influenced by Joan Didion. When I did the final draft of the book that was ultimately published, it had come a long way from its roots and had become a more tightly constructed work of fiction.

HUOJoan Didion leads us back to Alex, because she’s also provided inspiration for your work.

AIWell, the title for my talk show, As It Lays, is an homage to Play It As It Lays, a novel by Didion. I was also very inspired by her writing. Bret actually speaks about her writing in a way that resonates with how I’ve always felt about it, which is that its minimalism, her very direct way of writing, has a certain clarity that’s always really spoken to me.

HUODuring your first interview in 2010 for Purple magazine, Alex started the interview by asking Bret “You grew up in the Southern California. What was the best thing about it?” What is the best thing about it?

BEEThe geography of the place. It was a wide-open space that spread from the ocean to the mountains. You could get from one to the other in about thirty minutes. And it was the light. But it was also the mobility. There was a freedom to roam. And that freedom intensifies when you start to drive and you have a car. That sense of freedom influenced the range of my work; it leaked into other aspects of my life and into the idea that I could go as far as I did, for example, in my fiction. LA culture in the early 1980s, when I was a teenager, was very different. It was a much more innocent time. Things were fun. The beach was fun. Mall culture was fun. California punk culture was coming out of LA at the time. I liked it all. Until I didn’t. Until I started writing Less Than Zero. That’s when the darkness started to come in.

HUOAlex, you once said that the light, the water, the waves, the surfers, the sprawl, the cars, the status, and the city’s unique spirit was a source of inspiration for you while you were growing up there.

AIYes, it’s a unique place. And because there’s not much easy public transportation, you really do have a prolonged childhood, until you can drive.

HUOThere are some darker influences from LA as well. Bret, you once mentioned that the Manson murders had influenced you, along with Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter.

BEEWell, with the Manson murders, you couldn’t escape from them they defined the city for decades, still do to some degree. It debunked the friendliness of the city. People used to leave their doors unlocked, but the idea that someone could be roaming the canyons and just decide upon your house, well that kind of carnage really haunted everybody for decades in California; it created a lot of paranoia.

HUOAnd, Alex, for you?

AII was a child in the 1980s and that was a different moment. Los Angeles had just sent Ronald Reagan off to be president, tons of new development happened in the city, and it was a more optimistic period.

BEEWell, there was an exciting pessimism in LA in the late 1970s. I’m older than Alex, so I did experience that as a teenager—the defeat of the 1970s, the aftermath of Watergate and Vietnam—and it was a pessimism that was really quite thrilling; it affected the arts and music. Less Than Zero was attuned to that.

HUOWhat prompted you both to go deeper into a collaboration?

AIAbout a year and a half ago, I started working on a feature-length film project, a teen surf movie that I’m making, called SPF-18. But I didn’t know how to write a screenplay, so I had to hire somebody to help me. The movie is about the beach, and it needed to be earnest, for its teenage audience. I wanted to present a positive message to them. So, I contacted the guy who created Baywatch, his name is Michael Berk. We wrote the story together, and then he wrote the screenplay. And all throughout, I was really inspired by the process of working with a writer. I wanted to collaborate with a writer in another capacity in my work, which eventually turned into a more defined and concrete idea to create text paintings. And there’s no one I would have rather worked with, no one who is a more exciting or interesting writer in Los Angeles, than Bret.

HUOAnd then there was the dinner where it all started, right? It would be great to hear what really happened in this dinner, because I know that you collected fragments, and that these collected fragments then led to streaming thoughts. Can you tell us what happened there?

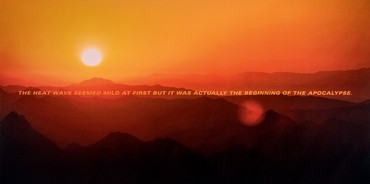

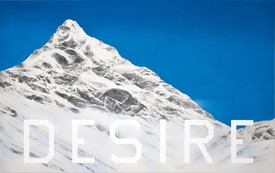

BEEWell, by the time we had dinner at the mall, we had already discussed the project. And my job was to create a narrative, a world that these paintings would take place in, and the text would be a reflection of the images that would also appear on the paintings. In the beginning, I created a world with scenarios set in Los Angeles that had reoccurring characters, houses, narrative trajectories, and began to whittle them down so they were just two or three sentences. During that first dinner, we went over the first batch of them. And there were many, many, many of them.

AIAnd we continued to collect them. Every time we had a new batch of texts to discuss, we would meet up for dinner and go through all of them together. And we just kept narrowing things down.

BEEYes. And then you started to find images that you thought would best juxtapose with these texts—Los Angeles, for a while, was really the subject matter. This process went on and on until we found what really worked best for the show, and created a coherent mood for all of the paintings.

HUOBefore we talk about the images, I wanted to ask you about the typography—the fonts, the way they are arranged.

AISo, once we had enough texts, I began turning them into images, sourcing stock photography and laying the texts out with the images, and with different fonts. The fonts were culled from the landscape of Los Angeles, so it was The Hollywood Reporter font or the Variety font, a font that’s used for screenplays, or the Whole Foods Market font. That’s how I got started.

HUOAnd then the images. You appropriated them, but it’s not really an appropriation.

AIWell, appropriation is more like shoplifting. When we collected images for this project, we were just shopping. We bought them online. We didn’t have to steal.

HUOBut are they readymades?

AIYes.

HUO You’ve used readymades before in your work, using all kinds of props; so it’s a continuation of that, one can say.

AIIn some ways, yes.

HUOIt might be interesting to hear a little bit about the timing of the exhibition, because you contextualized the exhibition timing both in terms of the art world and the world of cinema.

AIWell, the project is LA focused, and we wanted to present the work in a context that encouraged a heightened Hollywood situation around the art. There’s this annual Oscar-week opening at Gagosian in Beverly Hills. It’s a unique coming together of Hollywood and the art world in our city.

HUOAnd will the collaboration continue?

BEEHopefully, yes. We plan to create another group of these.

AIDo you find the process to be challenging?

BEEIt is very challenging, much more than I expected. Look, I believe everything should be enjoyable to a degree when you’re creating something, when you’re writing something, when you’re making something. But this posed a set of challenges that could be as trying at times as working on a novel. Now, I’m not saying it was like writing a novel. It was very different. But there was an inordinate amount of emphasis on finding the precise words, which would not only fit together best on a canvas, but would also be imbued with a meaning and communicated in a short amount of time. It was a long process. It took about a year: we went through hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of texts to get them down to the ones that are in the show.

HUOIt’s obviously very different from a traditional collaboration between an artist and a novelist or poet, which often gets reduced to a preface, or response to a work. Here it’s really a coauthorship.

AIYes, absolutely.

Artwork © Alex Israel and Bret Easton Ellis; photos: Joshua White/JWPictures.com, unless otherwise noted