Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Doug Pray is the director of the documentary Levitated Mass, which recounts the installation of the boulder of the same name, an artwork by Michael Heizer, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The subject of the film intrigued Pray from the moment he heard of it—the boulder, that is. “Before [the film’s producer Jamie Patricof] even finished his first sentence, about how a giant rock was going to have to travel through twenty-two cities and four counties in Southern California, I said, “I’m in. Let’s do this.”

The son of a geologist, Pray says that this giant rock tapped into his childhood. “Something that really struck a chord with me was how geology takes forever, which is the exact opposite of our ‘Instagram culture.’ Our society is instantly shared, which is why I have an appreciation for something that takes time. This, I came to realize, is an element of Heizer’s work too.”

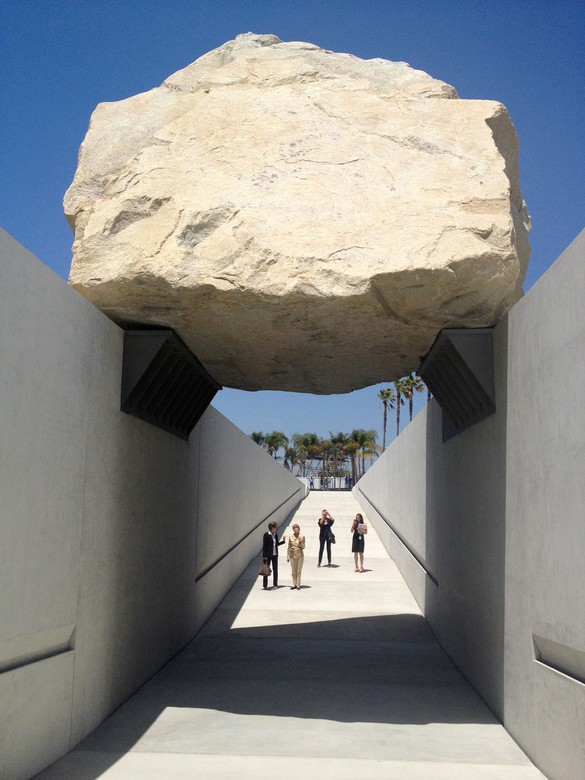

As the film took shape, Pray thematically divided it into three parts: There is the story of Michael Heizer the artist, and his body of work. There is the story of LACMA and the many obstacles it encountered—fundraising, coordination, permits, permissions, installation—in showing Levitated Mass. And then there’s the unexpected story of how the boulder’s transportation captured the public’s imagination. In the rock’s eleven-day migration, tens of thousands of people camped out on public highways to see it pass by on its way to the museum’s campus in the middle of Los Angeles.

Something that really struck a chord with me was how geology takes forever, which is the exact opposite of our “Instagram culture.”

Doug Pray

Heizer himself turned out to be the toughest hurdle for Pray. The artist has been living and working in the Nevada desert for nearly forty years, and is known for his reticence. He rarely grants interviews, preferring his work to speak for itself. “He was not into the idea of a big sit down, a formal chat,” Pray says. “He didn’t want to discuss his art’s meaning or its origins. That was off the table. I found that intriguing—and incredibly frustrating.” But what Heizer did grant was complete access to anything having to do with Levitated Mass, including filming during the six weeks that Heizer lived in an Airstream trailer on LACMA’s grounds and finalized the boulder’s installation. “He allowed me to make a rare portrait of the work itself. Anything having to do with that was fine.”

What did it take to move the rock? A lot of money, and a lot of coordination. Twenty-two cities had to agree to let the boulder pass through. It required road closures, the removal of traffic lights, and attracted unexpected crowds gathering—“which doesn’t happen for a lot of paintings,” says Pray.

Courtesy LACMA

Twenty-two cities had to agree to let the boulder pass through. It required road closures, the removal of traffic lights, and attracted unexpected crowds.

Derek Blasberg

Right up to the final moments, LACMA’s Michael Govan, who is a central figure in the film, and who championed the museum’s acquisition of Levitated Mass, wondered to himself (and to the camera) if the project would be completed. Throughout the film, there is constant questioning that it “might not happen.”

The tension leads to one of Pray’s favorite scenes in the film, in which we finally see the rock move. “By the time you get there you’ve seen all that goes into it; all the fundraising, all the bureaucracy, all of the energy that Michael Govan had to put into it. So, the second those 206 wheels start rolling, it’s such a big deal. I couldn’t believe it myself.” He recalls the mood at that moment: “Everyone felt as though we had been given a gift from the gods.” Everyone but Heizer himself. As the artist says in the film, “What art? There is no art. We’re working on something, it’s not built yet. Just moving some of the components around.”

The boulder’s journey came to an end at around 4:30 a.m. one morning, when it was deposited at LACMA. By then, people had jumped on bicycles to ride with the rock during its last leg. “It created such passion for so many people,” Pray says wistfully. “That’s what’s exciting about the film. Yes, it’s about art, and about Michael Heizer. But it’s also about the idea that if you want something badly enough, you can move mountains.” Or, in this case, a 340-ton boulder.